Celebrities

Louis Staples

Feb 09, 2020

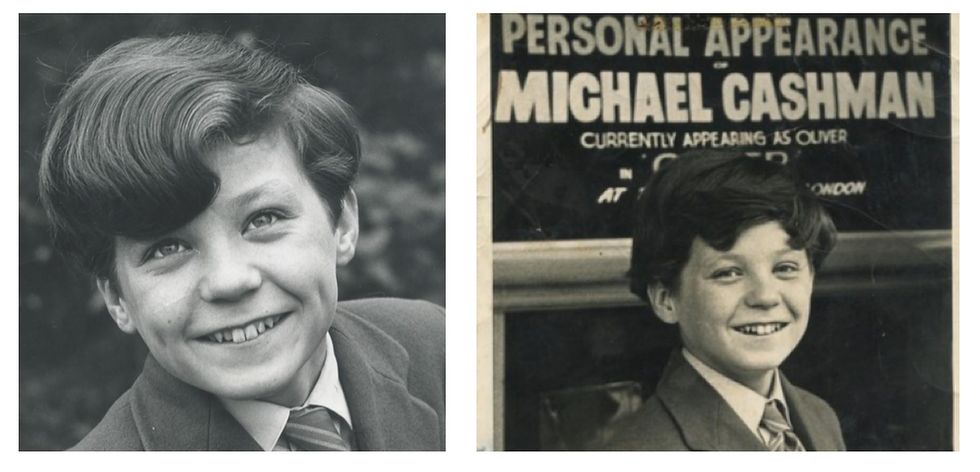

Michael Cashman

Michael Cashman’s life has had many beginnings, middles and endings.

Many people know him as one half of the first gay kiss they ever saw, which is quite the accolade to hold. As a successful actor, he found himself making history when, in the centre of the Aids crisis in 1989, EastEndersaired the first kiss between two men on British TV.

The scene generated hundreds of complaints and death threats. His address was printed (leading to bricks being hurled through his window), his partner was outed and tabloids accused him of having Aids. The right-wing press frothed with rage, with one article in The Sun (written by Piers Morgan, because of course it was), branding it a "love scene between yuppie poofs".

But Cashman’s own story is even more dramatic and complicated.

Born in 1950 in east London as one of four sons, his mother was an office cleaner (who spent Cashman's early years dodging debt collectors) and his father was a docker. Now, though, he sits in the House of Lords and counts Ian McKellen as a best friend and neighbour.

When we meet in his Limehouse flat overlooking the RiverThames, I’m surrounded by fragments of his world: portraits of his late husband Paul, awards from his acting days and photographs from his early years of LGBTQ+ activism. His new memoir, One of Them, puts his story on paper for the first time. The title is derived from the whispers he’d overhear as his mother chatted to her friends and chain smoked in their kitchen: was her theatrical, sensitive son “you, know, one of them?"

Cashman tells me that he was motivated to tell his story because, often, “people only see the superficial.” The “mosaic” of his life, he says, isn’t “complete” if you only look at certain colours – his successes, his loves, heroism and joys – while excluding the less pleasing shades. The first of these happens, with a jolt, in the book’s second chapter, when an eight-year-old Cashman is raped by an older man. As he took his first steps into showbusiness, predatory older actors and agents were a constant presence. He was groomed and abused for years by his first manager, who was supposed to keep him safe.

“I gained some things from that, but I’ll never know what I lost,” he says. “We must find the courage to move on with these experiences. Don't throw them away, because they will fester and capture you and pull you into darkness.”

Finding the courage to stand up to people is a recurring source of tension in Cashman’s story, from his drunken father screaming at his mother, to the men who raped him in childhood and adulthood. “Particularly as men, we're told we shouldn't talk about these things,” he says. “And as a young gay man growing up when people hurt you, attacked you and abused you. There was a part of you that had in your DNA, little voice say, ‘well, that's what happens to me because I'm queer, because I'm gay.’ My message is: ‘No, that doesn't happen to you, it should not happen to you.’”

This philosophy was central to Cashman’s decision to take the groundbreaking role in EastEnders, knowing full well the violent homophobic backlash it would create.

It also drove his political awakening: the campaign against Margaret Thatcher’s Clause 28, which prohibited public bodies from “promoting” (or mentioning) homosexuality. “Section 28 activated so many people,” he says. “The fact that it was brought in when a community was dealing with Aids and HIV is politically opportunistic and it was designed to give a death blow, particularly to gay men.”

The momentum of the Section 28 campaign prompted the co-founding of LGBTQ+ rights organisation Stonewall. The collective, which is now the UK’s largest LGBTQ+ rights charity, was co-founded by Cashman alongside 14 others including McKellen, actress Pam St Clement, activist Lisa Power and former Tory MP Matthew Parris.

Despite becoming a target of hostility and criticism from fringe factions of the LGBTQ+ community, Cashman remains supportive of Stonewall’s steadfast support of trans rights and thinks the 2004 Gender Recognition Act is “long overdue” for reform. “Do we ditch trans issues because they're difficult? No, that's all the more reason to pursue them,” he says. “I remember, many years ago, when lesbians would have nothing to do with gay mens’ rights and vice versa. And where bisexuals were misrepresented and shunned by both groups. But unless we defend the rights of the other than ultimately our own rights will go too.”

But not all queer activists, particularly those from Cashman’s generation, are united on this issue. Last year saw the formation of the LGB Alliance, a group of “gender critical” people who oppose reforming the Gender Recognition Act and Stonewall’s approach to trans rights. The group has faced frequent accusations of transphobia and homophobia since it was formed, with some LGBTQ+ people warning that they want the “return” of Section 28. They have denied these allegations.

When I ask about such groups, he refrains from mentioning them by name, because “if you can’t say any good, don’t say anything,” before adding:

“I don't understand the concept of any 'alliance' that shaves away the rights of others,”

“The younger generation has overtaken us. Their approach to life and gender fluidity is light-years ahead.”

After co-founding Stonewall, Cashman began to devote more and more time to the Labour Party, entering the European parliament in 1999. The process of switching one stage for another is a curious one (after all, don’t they say that politics is “showbusiness for ugly people”?) Cashman acknowledges that there are similarities; he still gets nervous before every “performance” to the Chamber and watches every speech back with a highly critical eye. But there’s one key difference.

“When you work in a theatre company, you have an absolute focus and absolute deadline to get that play done. Regardless of any difference, you come together,” he says. “In politics, different sides pull against one another. And that is often within your own party.”

Conflict within his own party is something Cashman has very recent experience of. After months of criticising Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership over its handling of antisemitism allegations and Brexit, he left the party after 45 years in May 2019 on the eve of the EU parliament elections. “I was reassured that things would happen, that it would be tackled. But there was a lack of commitment from Corbyn and people around him,” he says.

“I sit on Labour's benches in the House of Lords, reminding my colleagues that I haven't left the Labour Party, the Labour Party’s left me, it's drifted away from all of those values. But it will return.”

It is these twists and turns that Cashman’s late husband Paul Cottingham, who died of cancer in 2014 just five days before Cashman was inducted into the House of Lords, isn’t here to see. As the pages of his story turn, it’s clear that his biggest challenge, the major force he has to face, is the grief that brought his life to a standstill. The adventures the pair had – from exploring LA with David Hockney to having a threesome with a young Santa Claus on Christmas Eve in Florida – are interwoven with difficult periods in their relationship too, reflecting a life that was flawed but perfect.

“I see life in vibrant, vibrant colours,” he says. “When Paul died, that's where the all colour was wiped out of my life.” But after losing him, he no longer fears death.“Getting older is a gift if, like me, you find yourself still entranced by the world.”

As this chapter ends, Cashman finally feels content living in the moment. But looking ahead, to his next beginning, he sees himself on the forefront of defending human rights at this crucial point in British history, because there’s lots he still wants to achieve.

“I am always reminding myself that what we've got now is because generations ago, somebody said: ‘You can't do that’. But all it needs is one voice. One person can be the start of something.”

Michael Cashman's memoir One of Them is out now.

Keep reading...Show less

Top 100

The Conversation (0)

x