News

Jeff Guo

Jan 06, 2017

Picture:

Getty

For all of the ruckus over anchor babies and border walls and mass deportation, Americans know little about the nation’s immigrants.

Half of the public believes that immigrants make crime worse, when data shows they are actually more law-abiding than the native-born. Fifty-nine percent complain that immigrants aren't learning English fast enough, when in fact they are more fluent than past immigrants.

Despite fact check after fact check, these false stereotypes dominate. A new study shows that Americans wildly overestimate not only the number of immigrants in the country but also the number of immigrants who are in jail and the number of immigrants who can’t speak English.

It illustrates one of the ironies of the Information Age. At a time when the facts have never been more at hand, people are still stuck inside their own fictions.

A pessimistic explanation is that some people just don't care for the truth. Psychology experiments show that when we feel strongly about an issue, we fixate on sources that agree with us and ignore other evidence. Motivated reasoning is why some still claim that Ted Cruz’s father was involved in John F. Kennedy’s assassination or that Barack Obama is a secret foreigner, despite overwhelming proof to the contrary.

In a paper released last summer, political scientists Dan Hopkins, John Sides and Jack Citrin show that Americans who oppose immigration are much more likely to overestimate how many immigrants there are. The researchers tried to correct these false impressions by giving people a fact: Only about 13 percent of Americans are foreign-born. But this revelation didn't change people's underlying attitudes. Those who perceived immigration as a major problem continued to hold their concerns, even after they learned that the real number of immigrants was two to three times smaller than they had thought.

“Our findings suggest that attitudes toward immigration — like many political attitudes — are grounded in stable values and predispositions … that render these attitudes resistant to information that challenges existing beliefs,” the researchers write. The study provides further evidence, the researchers argue, that human reasoning works backward sometimes. We acquire or invent facts to fit a predetermined conclusion.

In this case, it may be that disliking immigrants causes people to rationalize their anxieties by imagining that immigrants are numerous and more threatening than in reality. That could explain why correcting their misbeliefs didn't affect people's opinions about immigration. Maybe they didn't believe the new information — or maybe the truth didn't matter to them in the first place.

That's one way to look at the problem. But maybe the picture isn't so bleak. In a new paper released last month, political scientists Alexis Grigorieff, Christopher Roth and Diego Ubfal show that the truth can sometimes nudge people into changing their attitudes toward immigrants.

The key, it seems, is that Americans are particularly concerned about immigrants being criminals or refusing to assimilate. The earlier study tried only to correct people's misconceptions about the total number of immigrants. But according to the researchers, many Americans will change their positions on immigration policy if you give them a reality check on some of these other anxieties.

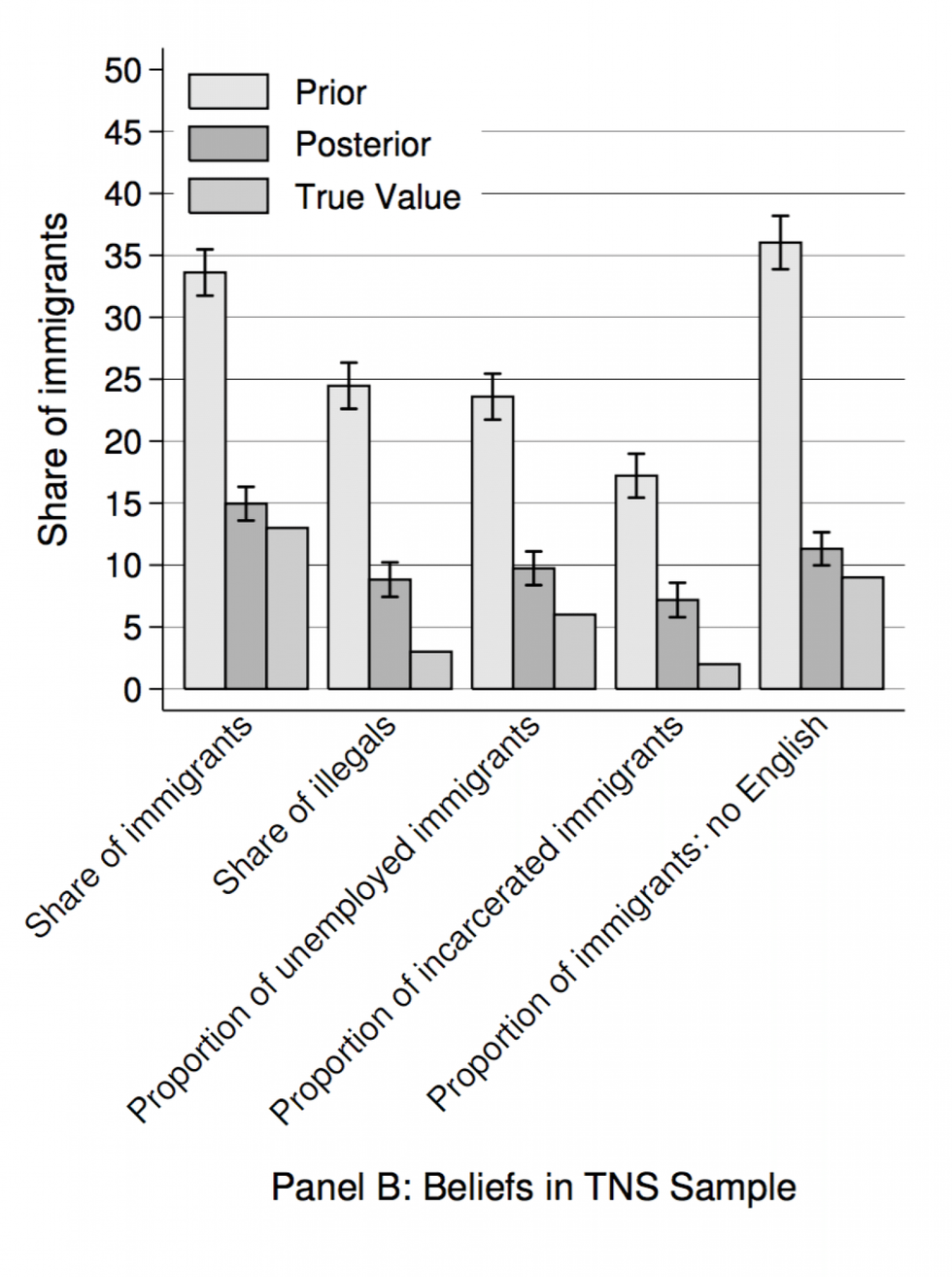

As this graph from the study shows, the public tends to assume the worst on a number of issues. Americans on average think that upward of 15 percent of immigrants are in jail; in truth, it’s less than 2 percent. Americans also believe that more than a third of immigrants can’t speak English; the real number is less than 10 percent.

The researcher experimented with giving people five facts, including the immigrant incarceration rate and the fraction of immigrants who can’t speak English. Subjects who were confronted about their negative misconceptions became more likely to view immigrants favorably and more likely to donate money to a pro-immigration charity. (This was real money — participants were given $10 and told that they either could keep it or give some of it to charity.)

After being exposed to the information, Republicans in particular became likely to favor increased legal immigration, as well as to sign a White House petition to increase the number of green cards, which would allow more foreigners to live in the United States permanently. This was particularly true of people who intended to vote for Donald Trump or Cruz in the primary.

Surprisingly, some of the changes persisted. When the researchers interviewed people four weeks later, those who had been exposed to the information still had more favorable opinions about immigrants, and the Republicans in the bunch were still more likely to support legal immigration. These weren't particularly large shifts — not everyone was swayed, and nobody’s opinions changed on the more issues, like amnesty for undocumented immigrants. But for such a mild intervention, the effects were notable.

Many political scientists tend to think that our beliefs are deep-seated and difficult to change. That’s why the results of an experiment last year, which showed that door-to-door canvassers can reduce prejudice against transgender people, were so stunning. Few expected that such a brief conversation could have an lasting impact on people’s opinions.

One theory says that immigration became such a flash point this past election because most people have the wrong idea about immigrants. An enduring mystery is how those false beliefs have persisted — why people are wary of immigrants even when there’s little evidence that they steal jobs or increase crime. Some of this may be stubbornness. But some people might be genuinely ignorant of the facts because they live in an information bubble.

Here, researchers have again shown that a slight nudge — just providing a little factual information — can affect how some people think. At a moment when fake news seems to be tightening its grip on the world, the experiment suggests that if we can do a better job informing the public, we might be able to have real, productive conversations — and maybe, just maybe, at a time when the nation has never felt more divided, we can resurrect the idea of democratic cooperation.

Washington Post

Top 100

The Conversation (0)

x