Robert White

Jun 19, 2025

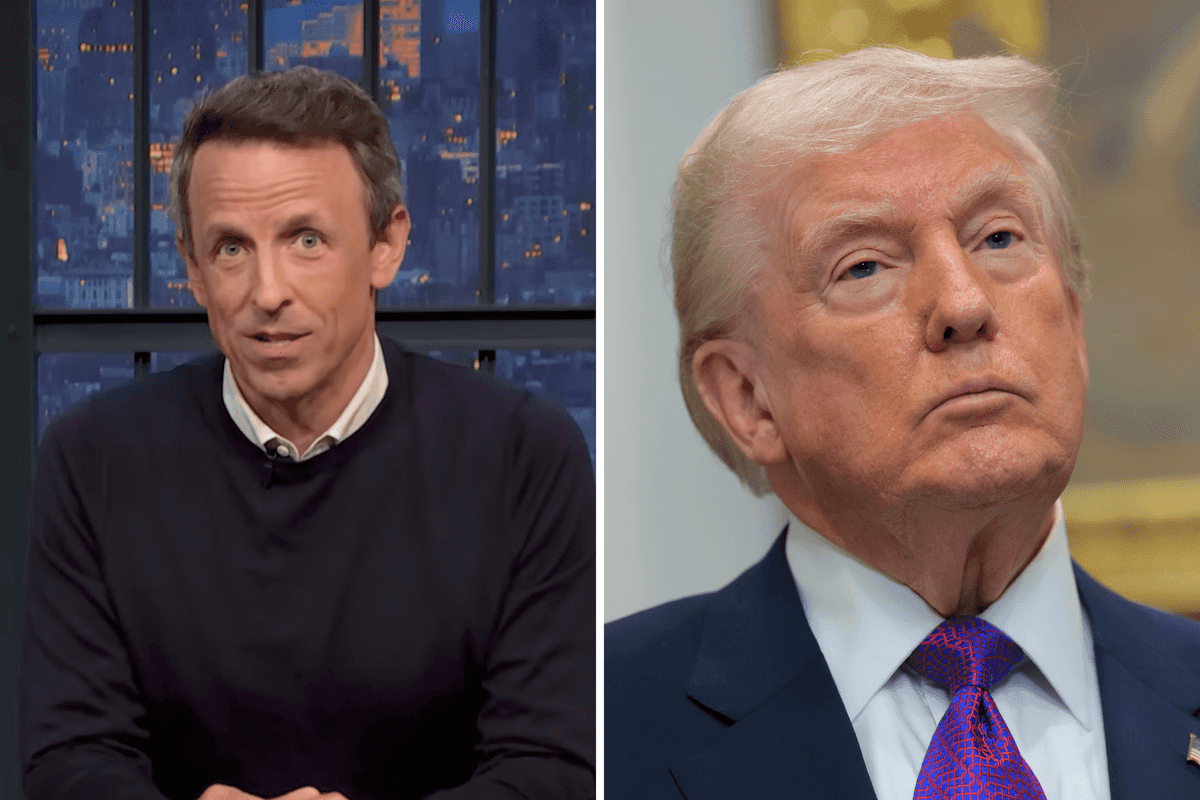

Mola senior building material specialist Han Li lays out the Roman plaster fragments (Museum of London Archaeology/PA)

An excavation in London has revealed one of the largest collections of painted Roman wall plaster to be discovered in the capital.

Archaeologists have spent four years working on thousands of fragments of shattered plaster discovered at a site in Southwark, near London Bridge station and Borough Market, in 2021 to painstakingly piece together the artwork of a high-status Roman building.

It is believed the frescoes once decorated at least 20 internal walls between AD 40 and 150, before the building was demolished and the wall plaster dumped into a pit before the start of the third century.

But now the reconstruction of the wall art has shed further light on high society in Roman Britain.

Many of the fragments were very delicate and pieces from different walls had been jumbled together when the building was demolished, so it was like assembling the world’s most difficult jigsaw puzzle

Han Li, Mola

The paintings – which display bright yellow panel designs with black intervals, decorated with beautiful images of birds, fruit, flowers, and lyres – demonstrate both the wealth and taste of the building’s owners, according to the excavation team at the Museum of London Archaeology (Mola).

Yellow panel designs were scarce in the Roman period, and repeating yellow panels found at the site in Southwark were even scarcer, making the discovery extremely rare.

Among the fragments is rare evidence of a painter’s signature – the first known example of this practice in Britain.

Framed by a ‘tabula ansata’, a carving of a decorative tablet used to sign artwork in the Roman world, it contains the Latin word ‘fecit’ which translates to “has made this”.

But the fragment is broken where the painter’s name would have appeared, meaning their identity will likely never be known.

Unusual graffiti of the ancient Greek alphabet has also been reconstructed – the only example of this inscription found to date in Roman Britain.

The precision of the scored letters suggests that it was done by a proficient writer and not someone undertaking writing practice.

Some fragments imitate high-status wall tiles, such as red Egyptian porphyry – a crystal-speckled volcanic stone – framing the elaborate veins of African giallo antico – a yellow marble.

Inspiration for the wall decorations was taken from other parts of the Roman world – such as Xanten and Cologne in Germany, and Lyon in France.

It took three months for Mola senior building material specialist Han Li to lay out all the fragments and reconstruct the designs to their original place.

He said: “This has been a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ moment, so I felt a mix of excitement and nervousness when I started to lay the plaster out.

“Many of the fragments were very delicate and pieces from different walls had been jumbled together when the building was demolished, so it was like assembling the world’s most difficult jigsaw puzzle.

“I was lucky to have been helped by my colleagues in other specialist teams for helping me arrange this titanic puzzle as well as interpret ornaments and inscriptions – including Ian Betts and the British School at Rome – who gave me their invaluable opinions and resources.

“The result was seeing wall paintings that even individuals of the late Roman period in London would not have seen.”

Speaking to the Today programme on BBC Radio 4, Mr Li said: “When you are looking at thousands of fragments of wall paintings every day, you start to commit everything to memory.

“You are sometimes working when you are sleeping as well.

“There was one time that I thought that this fragment goes here, and I woke up and it actually happened – so you could say I was working a double shift.

“But it’s a beautiful end result.”

One fragment features the face of a crying woman with a Flavian period (AD 69-96) hairstyle, hinting at the time period it may have been created.

Work to further explore each piece of plaster continues.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)