Science & Tech

Harriet Brewis

Feb 25, 2026

Lost Continent Found: The Incredible Discovery of Zealandia!

WooGlobe / VideoElephant

A landmass which was once home to up to half a million people has been discovered off the coast of northern Australia.

The now-submerged continental shelf was a vast, habitable landscape for much of the past 65,000 years, covering some 390,000 square kilometres (around 242,300 miles) – an area bigger than New Zealand

The scientists who made the landmark find, led by Kasih Norman of Queensland’s Griffith University, said that the “complex landscape” that existed on the Northwest Shelf of Australia was “unlike any landscape found on our continent today”.

And yet, the humans who lived there spoke similar languages and created similar styles of rock art to those living in the surrounding areas, the team announced in a news release.

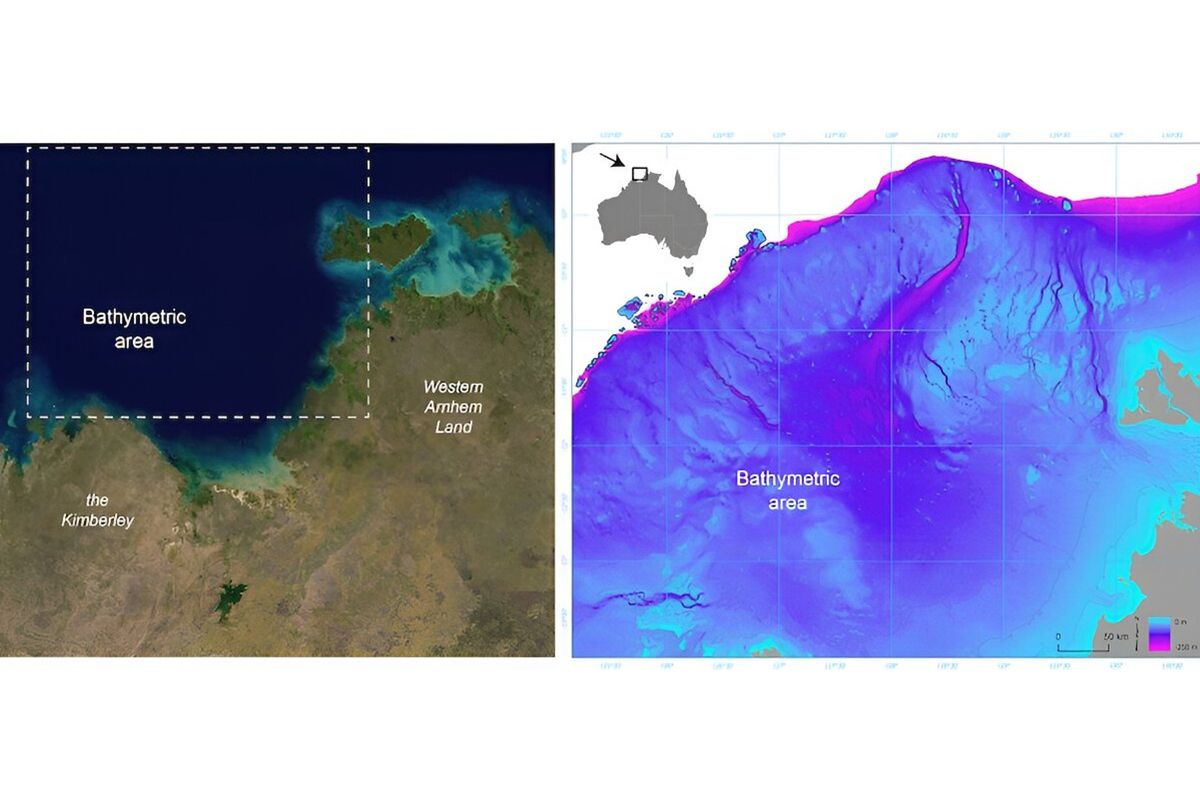

These regions, which were once connected by the shelf, still exist now: Western Arnhem land in the north and Kimberley in the northwest.

Norman and her colleagues explained that when the last Ice Age ended around 18,000 years ago, global warming caused sea levels to rise, which drowned out swathes of the world's continents.

This split the supercontinent of Sahul into New Guinea and Australia, and cut Tasmania off from the mainland.

The now-submerged continental shelves of Australia were thought to be environmentally unproductive and so largely ignored by original indigenous communities.

“But mounting archaeological evidence shows this assumption is incorrect,” the researchers wrote.

“Many large islands off Australia's coast – islands that once formed part of the continental shelves – show signs of occupation before sea levels rose.”

Still, before Norman and her team conducted their investigations, archaeologists had only been able to speculate about the nature of these sunken, pre-Ice Age landscapes, and the size of their populations.

But the newly-published findings have filled in many of the missing details – revealing that the Northwest Shelf was a lush realm, featuring archipelagos, lakes, rivers and even a large inland sea.

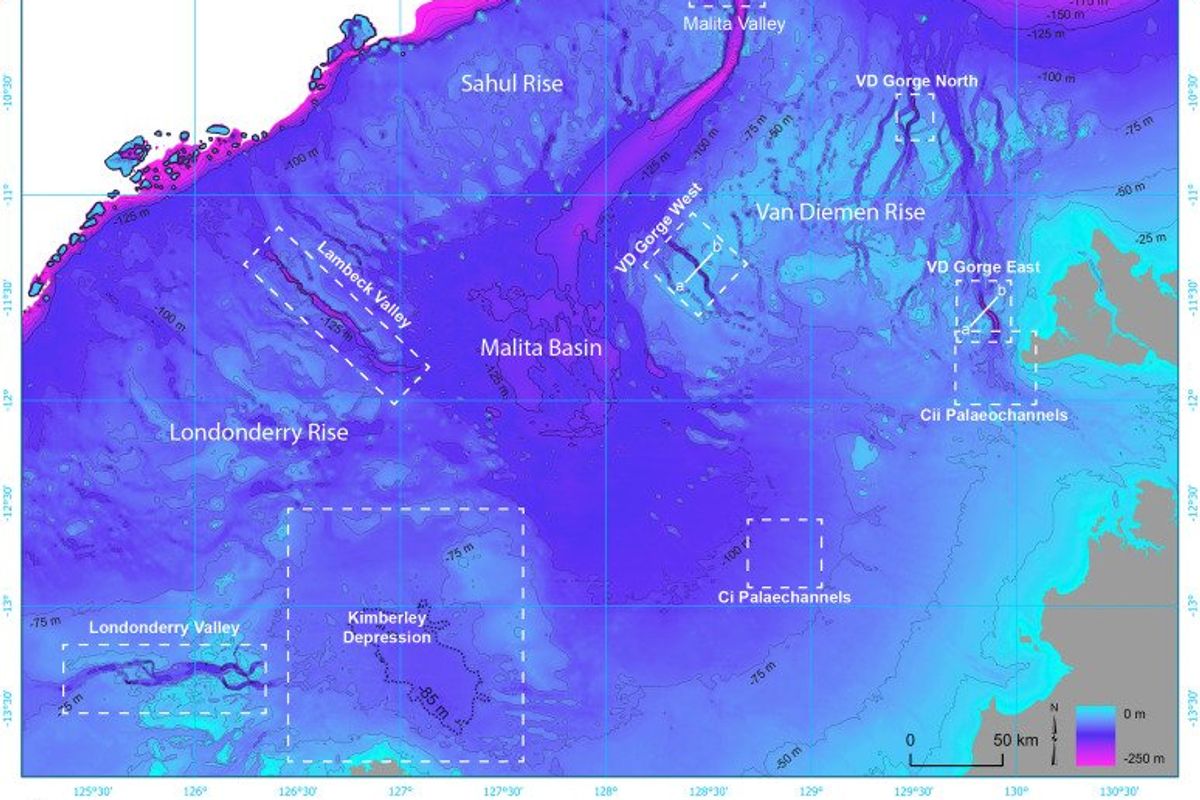

“The region contained a mosaic of habitable fresh and saltwater environments”, they said. “The most salient of these features was the Malita inland sea.”

This sea existed for 10,000 years (27,000 to 17,000 years ago), with a surface area greater than 18,000 square kilometres, according to the archaeologists.

The Northwest Shelf could have supported between 50,000 and 500,000 inhabitants at various times over the last 65,000 years, according to modelling conducted by Norman and her team.

The population would have peaked at the height of the last Ice Age, around 20,000 years ago, when the entire shelf was dry land.

To draw their conclusions, the researchers projected past sea levels onto high-resolution maps of the ocean floor.

They found that low sea levels exposed a vast archipelago of islands on the Northwest Shelf of Sahul, extending 500 kilometres towards the Indonesian island of Timor.

This archipelago appeared between 70,000 and 61,000 years ago, and remained stable for about 9,000 years.

“Thanks to the rich ecosystems of these islands, people may have migrated in stages from Indonesia to Australia, using the archipelago as stepping stones,” the scientists noted.

“With descent into the last Ice Age, polar ice caps grew and sea levels dropped by up to 120 meters. This fully exposed the shelf for the first time in 100,000 years.”

However, at the end of this Ice Age, rising sea levels drowned the shelf, forcing its residents to flee as waters encroached on once-productive landscapes.

“Retreating populations would have been forced together as available land shrank,” the experts wrote, noting that this resulted in “new rock art styles” appearing in both the Kimberley and Arnhem lands.

“Rising sea levels and the drowning of the landscape is also recorded in the oral histories of First Nations people from all around the coastal margin,” they added, pointing out that these histories are thought to have been passed down for “over 10,000 years”.

“This latest revelation of the complex and intricate dynamics of First Nations people responding to rapidly changing climates lends growing weight to the call for more Indigenous-led environmental management in this country and elsewhere,” they concluded their statement.

“As we face an uncertain future together, deep-time Indigenous knowledge and experience will be essential for successful adaptation.”

The full paper on their findings can be accessed via Quaternary Science Reviews.

This article was first published on June 23, 2024

Why not read...

- ‘World’s oldest pyramid' was not made by humans, archaeologists claim

- Structure double the size of world's tallest building found in the Pacific

- Incredible film of 'hollow island' in middle of ocean shared by divers

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings

Top 100

The Conversation (0)