Science & Tech

Harriet Brewis

Oct 03, 2023

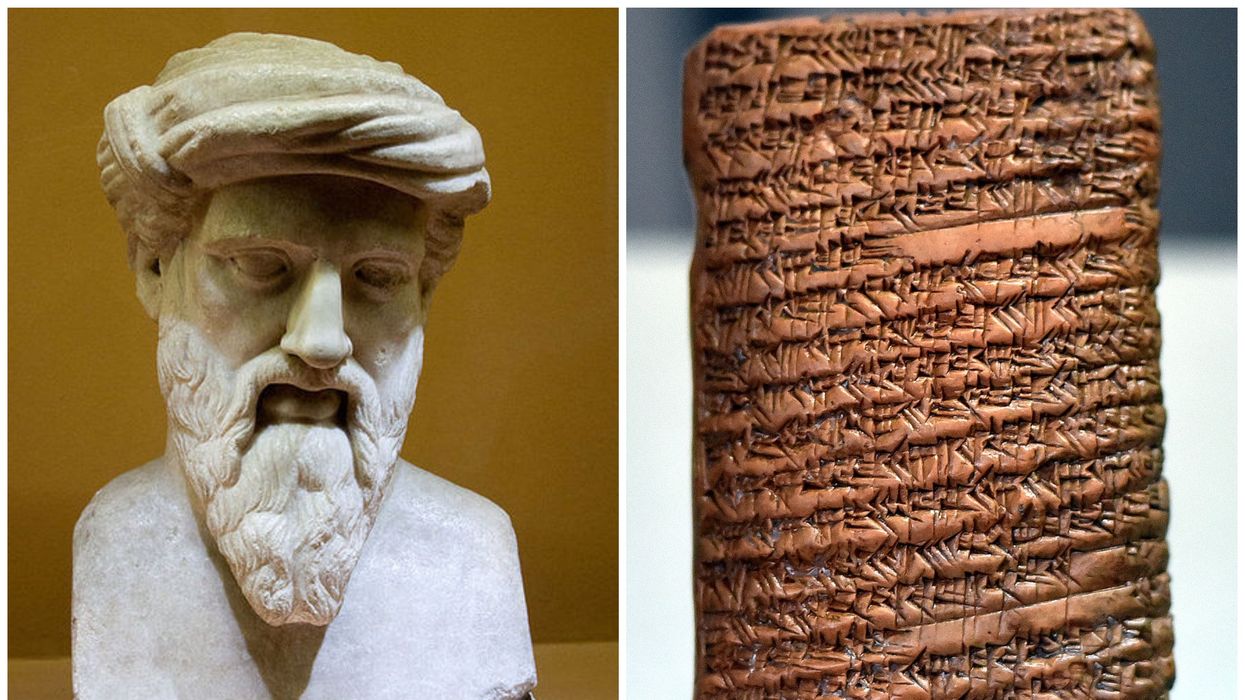

Tablets dating back to 1800 BC show that ancient Babylonian's were using Pythagoras's eponymous equation

Wikimedia Commons

For many of us, the mere words “Pythagoras’s theorem” are enough to revive pencil-smudged exercise books and desperate attempts to copy classmates’ work.

And yet, it turns out the name that has struck dread in countless school kids over the centuries is about as accurate as this writer’s attempts at geometry.

Because although it is assumed that the legendary Greek philosopher Pythagoras himself was to thank for the equation a2 + b2 = c2, it turns out it was being used some 1,000 years before his time.

Archaeologists have found the equation on a Babylonian tablet which was used for teaching back in 1770 BCE – centuries before Pythagoras’s birth in around 570 BC, as IFL Science notes.

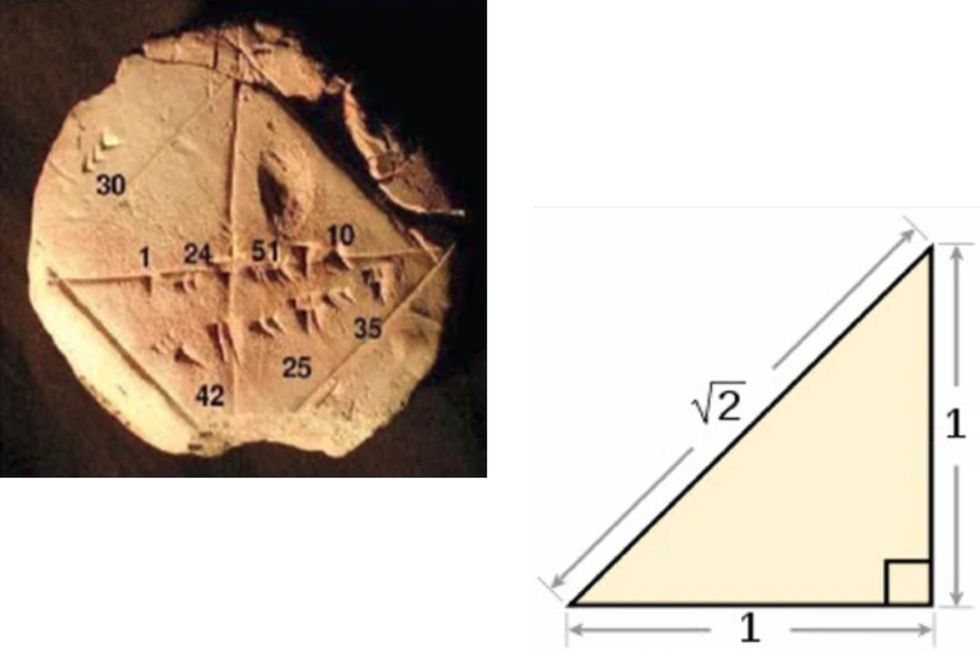

Another earlier tablet, from between 1800 and 1600 BC, even features a square with labelled triangles inside.

Translations of the markings, which followed the base 60 counting system used by ancient Babylonians, prove that these mathematicians were familiar with Pythagorean theorem (although, obviously, they didn’t call it that) as well as other advanced mathematical principles.

In a paper dedicated to the discovery, data scientist Bruce Ratner wrote: "The conclusion is inescapable. The Babylonians knew the relation between the length of the diagonal of a square and its side: d=square root of 2.

"This was probably the first number known to be irrational. However, this in turn means that they were familiar with the Pythagorean Theorem – or, at the very least, with its special case for the diagonal of a square [...] more than a thousand years before the great sage for whom it was named."

And yet, one key problem remains unsolved: why did the equation become equated with the famous Greek?

Well, most likely because Pythagoras wanted it to be.

In his paper, Ratner points out that although the Ionian icon is widely considered the first bonafide mathematician, little is known about his specific mathematical achievements.

Unlike his successors, he didn’t write any books that we know of, so there’s no written evidence of his work.

However, we do have proof that he founded a semi-religious school called the Semicircle of Pythagoras, which followed a strict code of secrecy.

As Ratner explained: “Pythagorean knowledge was passed on from one generation to the next by word of mouth, as writing material was scarce. Moreover, out of respect for their leader, many of the discoveries made by the Pythagoreans were attributed to Pythagoras himself.

“Consequently, of Pythagoras’ actual work nothing is known. On the other hand, his school practiced collectivism, making it hard to distinguish between the work of Pythagoras and that of his followers.

“Therefore, the true discovery of a particular Pythagorean result may never be known.”

Still, he stressed, even though Pythagoras wasn’t the brains behind the most famous formula in maths, he does deserve a little credit for putting it on the map.

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)