News

Jake Hall

Jul 24, 2018

Photo: Getty Images / Alexander Hassenstein, Screenshot: Twitter / @_beardus

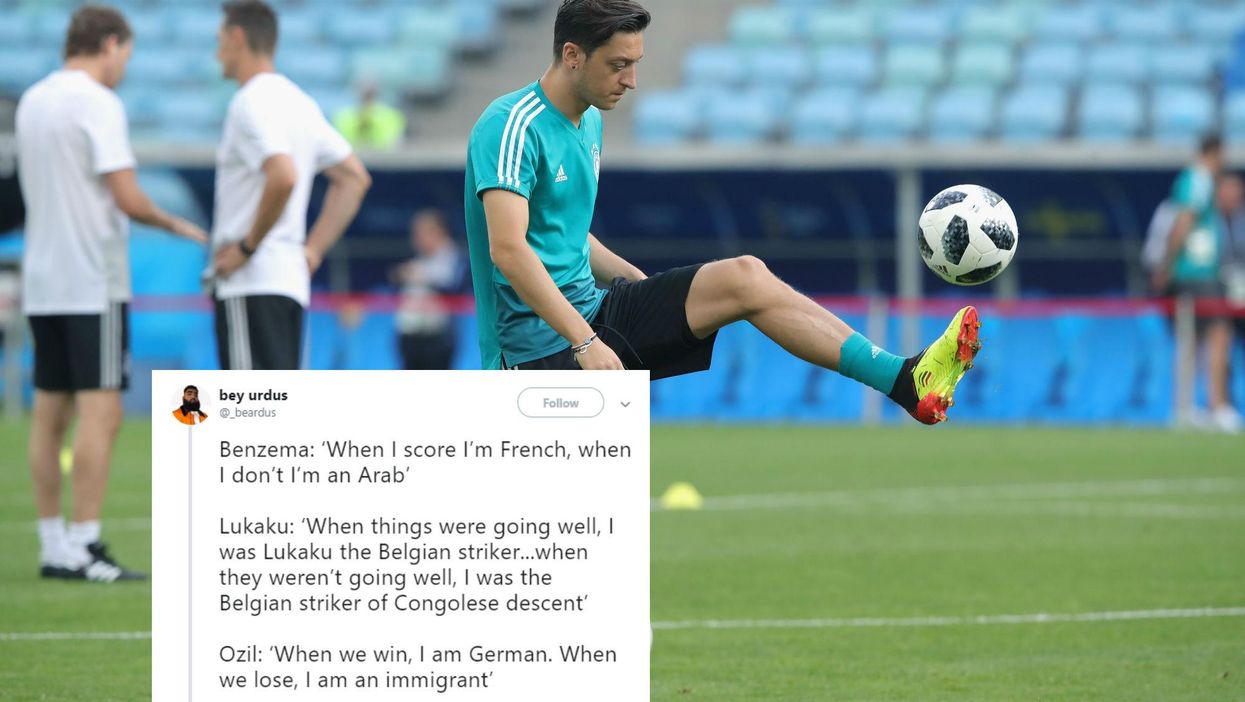

It’s been a few weeks since the dust settled on the 2018 World Cup, but discussions of the tournament’s most successful players are still making headlines. The reason? Racism.

This week, German footballer Mesut Ozil resigned from the national team, releasing a series of explanatory statements alongside his announcement.

In these statements, Ozil explained that he felt the backlash surrounding a recent meeting with the prime minister of Turkey was tinged with "racism and disrespect".

He underlined clear media double standards, stating:

I am German when we win, but I am an immigrant when we lose.

Ozil isn’t the only World Cup star to express these feelings. Swathes of celebratory articles praised the World Cup’s multiculturalism, as well as the extent to which players born into immigrant families were responsible for the tournament's biggest success stories. CNN even described France’s triumph as a “victory for immigrants everywhere".

But this celebratory narrative tends to disappear when the players aren’t so successful - a fact noticed and shared by Twitter user @_beardus.

Statements like these seem to highlight that the rhetoric of the ‘good immigrant’ – the idea that a country will readily accept you as long as you’re successful, often extraordinarily so – is alive and well.

In 2016, author Nikesh Shukla explored this concept in-depth. Frustrated by a general lack of diversity in publishing, – which he now directly works to rectify through his literary agency, the Good Literary Agency – Shukla asked a series of writers from different minority ethnic backgrounds to write essays about their experiences.

The results were compiled and published in The Good Immigrant, a best-selling book which broadened narratives around race, nationality and nationhood while simultaneously dispelling the myth that there is any single, monolithic BAME (Black, Asian & Minority Ethnic) experience.

Shukla has written in-depth about this year’s World Cup, most recently in a column for The Guardian.

Speaking to indy100, he explained:

One of the most interesting things about this year’s World Cup is that, in a weird way, I felt less conflicted about supporting England.

After years and years of being told to 'go home', that chant of 'It’s coming home' made me feel like there was a shared understanding of what 'home' meant, and that included me.

Other writers have described the World Cup in similar terms – in an increasingly fragmented country, the England team’s success in the competition seemed to offer us all a joint cause for celebration.

But Shukla agrees with Ozil's insinuation that immigrants must work hard in order to be accepted.

One example is the French refugee that was granted citizenship after he scaled a building to rescue a child.

He was given French citizenship because he did something extraordinary, but if he hadn’t done that, where would he be now?

He describes the constant tightrope that people of colour are forced to walk, and argues that descriptions of Lukaka in particular highlighted the ways in which some countries are still ‘othered’: 'The implication in Lukaka’s statement is that being Belgian is fine, but being Belgian and of Congolese descent is lesser. It’s a subtle use of language, but that’s ultimately the message; he’s not one of us, and therefore he’s not good enough.'

Shukla says he’s familiar with this rhetoric despite being born and raised in England:

I get told to ‘go home’ all the time, but I was born in the UK.

So when you spend your entire life trying to define for yourself where you’re from, and what your identity is, to have people pull the rug from under you fucks you up.

Wei Ming Kam, who works in digital marketing and also advocates for minority representation in publishing, agrees that the narrative surrounding immigration in the UK in particular hasn’t changed – 'in fact, I think in many ways it’s worsened,' she says, pointing to the well-documented rise in fascist ideology across Europe.

The outrage over the Windrush citizens came years too late, and was largely built on how outrageous it was they had worked ‘so hard’ for Britain yet still been treated so inhumanely.

I find it telling that the good immigrant / bad immigrant narrative dominated the media cycle over people who were actually citizens of the UK.

It suggested that people never saw them as really ‘belonging’ here; that they had proved themselves ‘worthy’ of being able to claim citizenship – a status which they technically already had!

The Windrush scandal highlighted the crucial role that immigration played in the rebuilding of post-war Britain, yet media coverage surrounding the controversy largely strengthened the argument that the UK is willing to accept immigrants only when they're deemed useful.

“The media is complicit in allowing far-right bigots to have national platforms where they promote, unchallenged, the narrative of too many immigrants ‘changing the culture’ of Western countries,” explains Kam.

“What they really mean is that it’s not enough for immigrants (or those they perceive to be immigrants) to be ‘good’ anymore, and that the economic advantages that immigration brings does not make up for the barely-suppressed fear of white people becoming the minority.”

She also notes that conversations around immigration are almost always racially-charged, and that white immigrants rarely get questioned about their ancestry.

In Western countries, ideas of immigration, citizenship and ‘belonging’ have always been based on a racial hierarchy. If you’re a white immigrant, you will rarely be questioned about your immigration status, or about where you’re ‘really from’.

If you’re a person of colour, those questions will be asked regularly, and often enforced by Home Office policy.

Here, she cites the NHS surcharge as an example of this discriminatory double standard before pointing to the ways in which the ‘good immigrant’ narrative is often used to pit different minorities against one another. Kam also underscores the fact that this narrative is disproportionately used to denigrate black communities, as various articles have highlighted.

We are not given the space to be humans; to fail, to make mistakes. Any misstep is used to demonise us immediately.

People of colour in the UK have always been held to a higher standard, and I do not see this changing.

In essence, the racially-charged language of the aforementioned World Cup coverage can be examined through a wider lens to prove that racism is often nuanced, and can be communicated through subtleties in language imbued with nastier connotations.

“Ultimately, it’s a new form of racism,” summarises Shukla. “Instead of using slurs to describe people, it’s about reminding them that they’re on precarious ground.”

It’s basically saying ‘If you do well, we’ll accept you. If you do badly, you can f*ck off back to where you came from.’

More: ‘I am an immigrant’: Guillermo del Toro makes a powerful acceptance speech at Oscars

Top 100

The Conversation (0)