Harriet Brewis

Oct 04, 2023

Three scientists win Nobel Prize in physics for looking at electrons in …

FMM - F24 Video Clips / VideoElephant

“Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so” – so wrote Douglas Adams in his iconic novel ‘Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’.

But, it turns out, time is not only real but measurable down to the attosecond.

And if you think your lunchtime passes too quickly, just wait till you see how short one of these fractions of a second is…

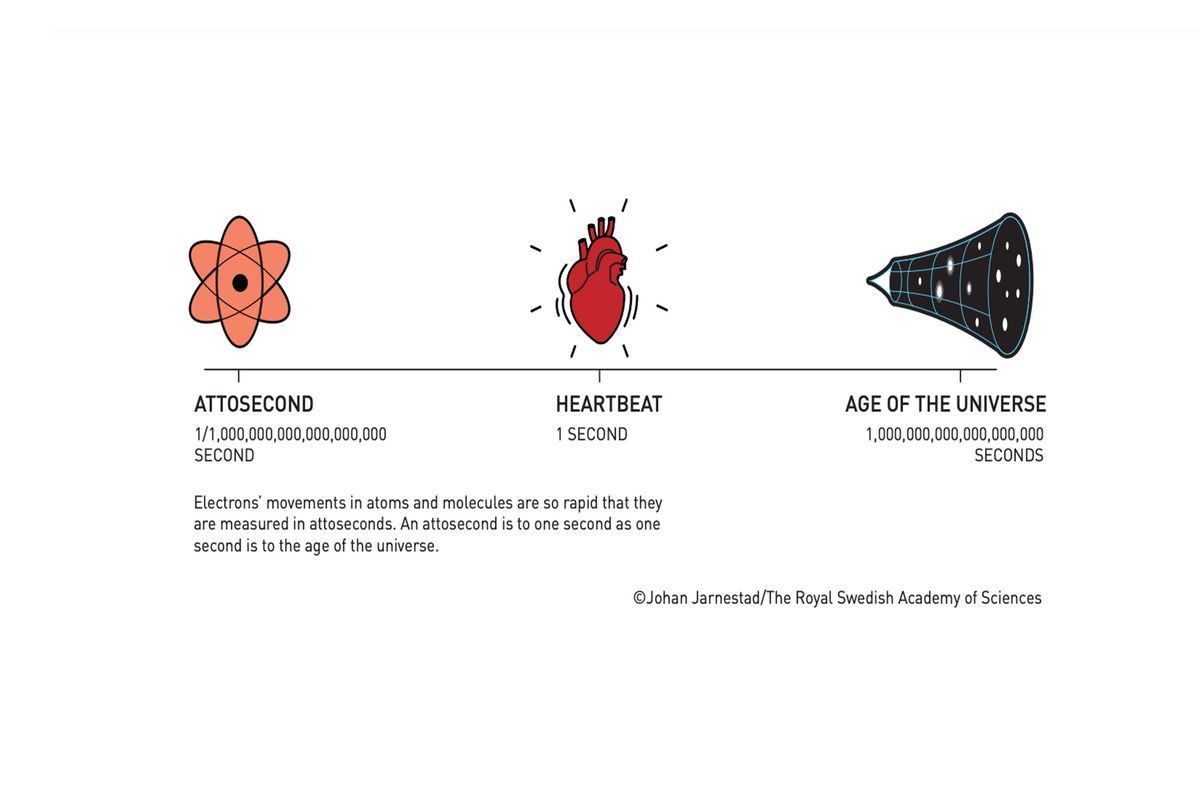

A billionth of a billionth of a second.

For context, there are as many attoseconds in one second as there have been seconds since the birth of the universe some 13.8 billion years ago.

Or, if you’d prefer a visual explanation, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has provided this handy illustration:

It’s perhaps unsurprising that attoseconds are, according to Hans Jakob Woerner, a researcher at the Swiss university ETH Zurich, "the shortest timescales we can measure directly".

So what’s the significance of all this?

Well, interest in the attosecond has been sparked by this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics, which was won by a trio of scientists for creating a window into the elusive world of electrons.

Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L'Huillier found a way to create mind-bendingly short pulses of light that can be used to measure the processes that take place inside atoms and molecules.

When it comes to electrons, changes occur in a few tenths of an attosecond, so these movements (which occur within atoms and molecules), were long considered impossible to trace.

However, thanks to Agostini, Krausz and L’Huillier’s work, we can now capture images of such fundamental processes. And this technology has the potential to drive major breakthroughs in a number of key areas.

These include electronics – because it is important to understand and control how electrons behave in a material – and medical diagnostics. For example, in detecting molecular traces of diseases in blood samples.

Hungarian-born Krausz, whose team generated the first ultra-fast pulses in the early 2000s, has likened attosecond physics to a fast-shutter camera where the short light flashes allow a freeze frame look within the microcosm.

"Just as you try to photograph a Formula 1 racing car with a fast camera, for example, as it runs through the finish line. You need a camera to take sharp snapshots and reconstruct the movement," he told the Reuters news agency.

"This is exactly the concept we use for the fastest movements that happen in nature outside the atomic nucleus, which is the movement of electrons."

Hailing the trio’s Nobel recognition, Eva Olsson, a member of the physics prize’s selection committee said: "The ability to generate attosecond pulses of light has opened the door on a tiny, extremely tiny, time scale and it's also opened the door to the world of electrons.”

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)