News

Jake Hall

Jun 12, 2018

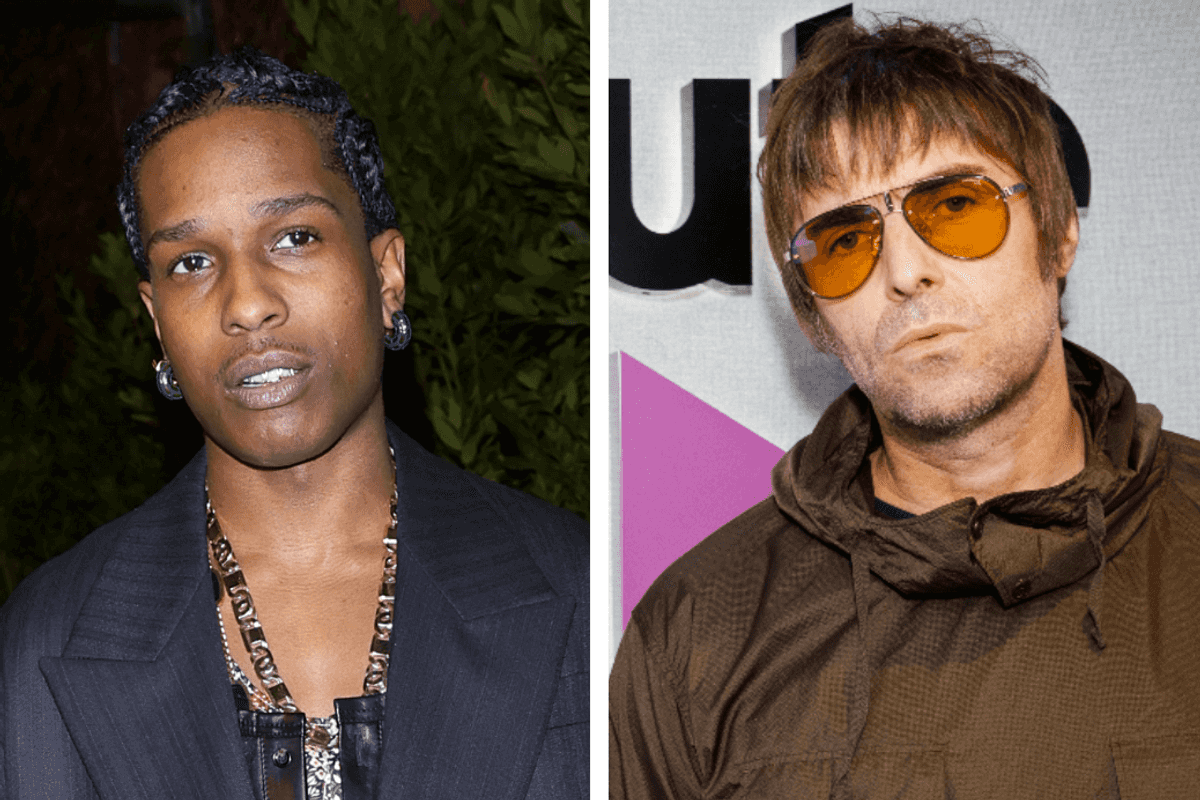

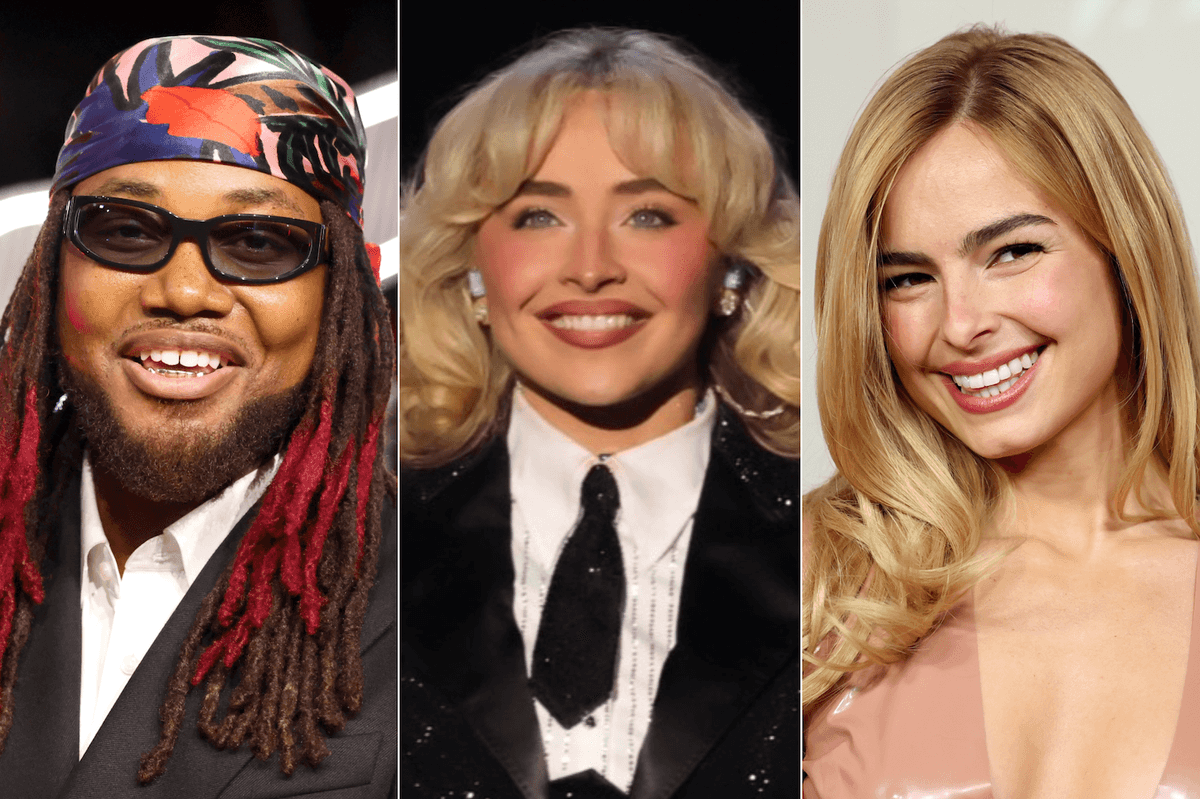

Photo by Alex Douglas, Courtesy of Vicky Beeching

The last few years have been tumultuous for Vicky Beeching, a former rock star who built a reputation as one of the best-known writers and performers of religious music in the world.

But, in 2014, Beeching made the courageous decision to come out as gay, essentially ending her music career in the process. "The decision wasn't mine to make," she explains to indy100. "Once I came out, my music career was over because the mega-churches, religious festivals and Christian conferences I used to be part of slammed the door on me, which was heartbreaking. The whole thing just ended right in front of my eyes."

Since then, Beeching has invested her energy into writing, broadcasting and campaigning tirelessly for LGBT+ rights; and now, she's made the decision to release a searing memoir, Undivided, about her own unique life experiences.

"It's a book for anyone and everyone, because it deals with the broad themes of authenticity, facing your fears and living the fullest life possible," she states when describing the book and the readers she thinks it will resonate with. In particular, she expresses hope that her life story might offer comfort to LGBT+ people in similar circumstances, as well as an education of sorts for those who don't know what it means to be marginalised:

I hope it educates parents, priests, school teachers and those in the workplace, helping them realise what it can be like to be part of a minority group and to feel excluded.

On this subject, Beeching speaks from experience.

As a child, she was taught how to play numerous instruments by her mother, who was the leader of musical worship at their local church in Canterbury, Kent. Beeching quickly discovered a talent of her own, and began writing songs at the tender age of just ten years old. This passion sustained itself throughout her early years, so she soon moved to Nashville, Tennessee in order to focus full-time on writing and recording worship music, an influential genre particularly popular across America's Bible Belt. Her risk paid off; soon, she was one of the most influential musicians in the industry.

This is the story we know so far, but in Undivided she speaks of an adolescence spent wrestling with her sexuality. In the last few years she's written about the damages caused by conversion therapy, psychological treatment based on the belief that sexuality can be 'cured' through prayer, a topic she covers in more depth throughout the book.

"It's dangerous and harmful to suggest anyone can be turned from gay to straight, but some churches still advertise this and practice it behind closed doors. I believe it has to end before more lives are damaged."

I've been through various forms of conversion therapy. Some were more dramatic, like an exorcism when I was 16, and some more subtle, like conversion therapy courses and books in my 20s.

All were equally harmful in making me feel like I was sinful, broken and needed to become a different person in order for God to love and accept me.

"Those experiences made me divorce myself from my own feelings, attractions, and physical body, so I ended up a very dissociated adult. It's taken a lot of counselling to heal that damage, and I'm still dealing with some of the fallout today." She states, unequivocally, that conversion therapy should be banned,

This isn't the only issue, either; if you took a glance at most mainstream media outlets, you'd likely be convinced that religion and LGBT+ identities are fundamentally incompatible. This misconception was reinforced recently, when a religious bakery in the USA made international headlines for refusing to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. The case went to court, and the bakers won - their right to religious freedom outstripped the rights of LGBT+ people.

"The reason those views exist is because of the way many Christians interpret the Bible," explains Beeching.

A handful of verses are understood by some to prohibit same-sex relationships, but the church often gets it wrong when translating what the Old and New Testament actually mean for us today.

"For example, the church used the Bible to oppose William Wilberforce, arguing that the Bible defended slavery as something acceptable. Likewise, the church used the Bible to oppress women and to stand against the Suffrage movement, saying the text taught that women should submit to men, and accept male authority."

It's time to look at the Bible with fresh eyes on the topic of LGBT+ equality and realise those verses have been misunderstood, just as the verses about slavery and women were.

Also, it's not just an academic issue to be discussed by church officials - it's about life and death for people like me.

"Sadly, the Bishops and pastors usually making the decisions are straight white men, so they are not able to understand firsthand what it's like to be LGBT+ and Christian. Our voices and experiences need to be heard in those discussions."

But diversifying the church isn't necessarily as easy as it sounds on paper. In fact, Beeching explains that she'd love to become a priest, but has never been able to do so due to church teaching.

Still today, the Church of England makes every priest promise to live by their official teachings on sexuality - agreeing that same-sex marriages are sinful, and not suitable for anyone in the priesthood. I cannot agree with that, so until that teaching changes, I am blocked from priesthood.

"It's sad that people like me, who are passionate about faith, and passionate about making spirituality relevant to a younger generation, can't serve in that way. Especially when church attendance numbers are on the decline. I know lots of other LGBT+ people in their 20s and 30s who are in the same position - wanting to serve as pastors but held back for the same reason. Meanwhile, we have to watch as the Church of England's PR messages go out on Twitter and Facebook, encouraging people our age to come forward for the priesthood. It's difficult to feel excluded just because we're gay."

It's not just sexuality that can cause a problem, either; it's gender, too.

In Undivided, Beeching speaks about being made to feel that she had been 'shortchanged' as a woman, made to feel like a second-class citizen in a male-dominated institution. Despite rising to international prominence and earning considerable respect as a speaker and a voice for the community, she recalls feeling looked down on, or dismissed by both UK and US churches still fixated on the archaic myth that only men can preach or lead churches. "That sexism compounded with homophobia really felt like a double blow to deal with," she laments.

Not only is this mentality toxic, regressive and misogynistic, it comes with consequences for women. Structural hierarchy is always built on the abuse or exploitation of the most marginalised; Beeching writes that she experienced this abuse herself, detailing a harrowing incident of sexual assault.

In the book, I write about an incident where a male priest sexually assaulted me, and I decided it was important to speak out abut that now.

Often, male leadership is seen as unquestionable in churches, so women can feel unable to speak up for fear of not being believed. I kept silent about my experience, which happened at the age of 18, for that very reason.

Only by shining a light on these issues will they be changed.

Despite penning an engaging, no-holds-barred exploration of the church, institutional religion and discrimination, Beeching remains optimistic that change is happening. She points to the Church of England's ruling to allow women to become priests and bishops as a vital step forward which, although it won't end sexism and gender inequality, offers hope. This official change is increasingly coupled by grassroots activism - "lots of people and organisations are working hard on this," she enthuses.

Personally, Beeching says that much of her campaigning work occurs on a one-to-one level with pastors and leaders who, as they get to know her, become more receptive to the idea that LGBT-inclusivity is the way forward. Despite pushback from the Church of England in particular, Beeching reiterates that "there is change happening slowly but surely - one brilliant example is the many Christians who join Pride marches across the UK every years, and have a very visible presence. That gives me hope for a brighter future."

This optimism is heartening, but Undivided makes it clear that Beeching hasn't always felt so positive. Various studies show that LGBT+ people and minority groups more generally are disproportionately susceptible to mental health issues; everyday discrimination can truly grind down even the most resilient among us, often exacerbating existing issues. Furthermore, many of us feel unable or afraid to speak openly and honestly about these issues, creating a vicious cycle which can feel impossible to escape. Beeching details feeling trapped in the cycle in her memoir, writing that at one point she was even contemplating suicide.

"I did wonder about sweeping that aspect of my journey under the carpet, but I decided to share it, as I believe we need to talk more openly about the issue and how we can help get one another through our darkest moments," she says of making the decision to discuss her own struggles with such candour. "It has been hard to come to terms with the fact that the teachings of the church were what drove me to contemplate suicide," Beeching continues.

I love the church and I try to forgive the homophobia I've experienced there, but years and years of being taught that same-sex relationships are 'sinful', 'deeply shameful' and 'an abomination' wore me down to the point of extreme isolation and despair.

Because of my well-known leadership role in churches across the UK and US, I felt totally trapped. It got to the point where I was unspeakably lonely and could no longer imagine a positive future for myself, so I considered ending my life on several occasions.

She also highlights the fact that discussions of mental health within the church rarely consider that homophobic teachings might be part of the problem. "The church should be the safest place for anyone to go if they're struggling with depression, anxiety or extreme isolation, but for me, it was the very place that caused my mental health issues by making me feel shameful and broken for my attraction to women."

Beeching may have seemingly overcome her own struggles and dedicated herself to fighting for real, tangible progress, but what would she say to anyone who's young, struggling and feeling unable to discuss their sexuality?

"I would say that it's totally fine to be gay and Christian; that God loves them for exactly who they are, including their sexual orientation. I'd also encourage them to reach out online to LGBT-affirming people like myself, as we can help connect them with organisations and churches to support them." This message seems genuine; it's clear that Beeching wants to enable discussion and offer vicarious support and solidarity by describing her own life experiences.

More than anything, her work sends a resounding message: that, no matter how many obstacles you face, there is a community and a world willing to accept you. Things can get better.

"I'd really urge anyone who has ever been driven to the point of suicidal thoughts, as I was, to believe life can get better, and that the years ahead can be full of love and hope," she reiterates.

Things are changing within society and within Christianity, so reach out, get support and know that there's a whole family of us out there waiting to help you on your journey.

You're never alone, and it is possible to step into a brighter future.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)