News

Max Ehrenfreund

Nov 22, 2016

Transition 2017/YouTube

It is hard to compare Donald Trump to anyone else in American politics, especially when it comes to the economy.

The president-elect plans to combine restrictions on goods imported from abroad, which are usually advocated by liberal politicians, with conventionally Republican policies, such as tax relief for the wealthy and major corporations, along with more federal borrowing.

More than any U.S. politician's platform, Trump's agenda on the economy resembles those of populist leaders abroad. In particular, the policies he has proposed are very similar to those of Dilma Rousseff, the former president of Brazil who was ousted from office in August.

As Trump has planned to do, Rousseff enforced restrictions on imports. She promised new spending on infrastructure and granted generous subsidies to corporations with the goal of stimulating the economy, especially manufacturing.

“It’s a very similar program,” said Riordan Roett, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University and an expert on Latin America.

While there are a number of important differences between the Brazilian and U.S. economies, Rousseff's policies arguably offer a cautionary example for newly empowered Republicans in Washington. The Brazilian economy is in a severe and persistent recession. Gross domestic product contracted 3.8 percent last year, according to the International Monetary Fund, which projects a decline of 3.3 percent this year.

Inflation accelerated to an annual pace of 10.6 percent earlier this year, according to the Central Bank of Brazil, and while prices are not increasing as fast as they were, the unemployment rate has climbed to 11.8 percent as of last quarter.

“The challenges are pretty massive,” said Monica de Bolle, an economist and Roett's colleague at Johns Hopkins, who has written about the similarities between Trump and Rousseff.

“It was a combination of protectionism and fiscal expansion,” said de Bolle, who is also a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Now the day of reckoning has come.”

The economy was expanding at a rapid pace of 7.5 percent in 2010, the year before Rousseff took office. Exports to the global commodity market were helping to sustain the expansion and to pay for the populist agenda of Rousseff's predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, also of the leftist Workers' Party.

Rousseff built on his policies. Her administration continued extending cheap credit to major Brazilian firms through the government's development bank. These costly subsidies, combined with other tax credits, contributed to an increasing deficit. So did a decline in prices for commodities worldwide.

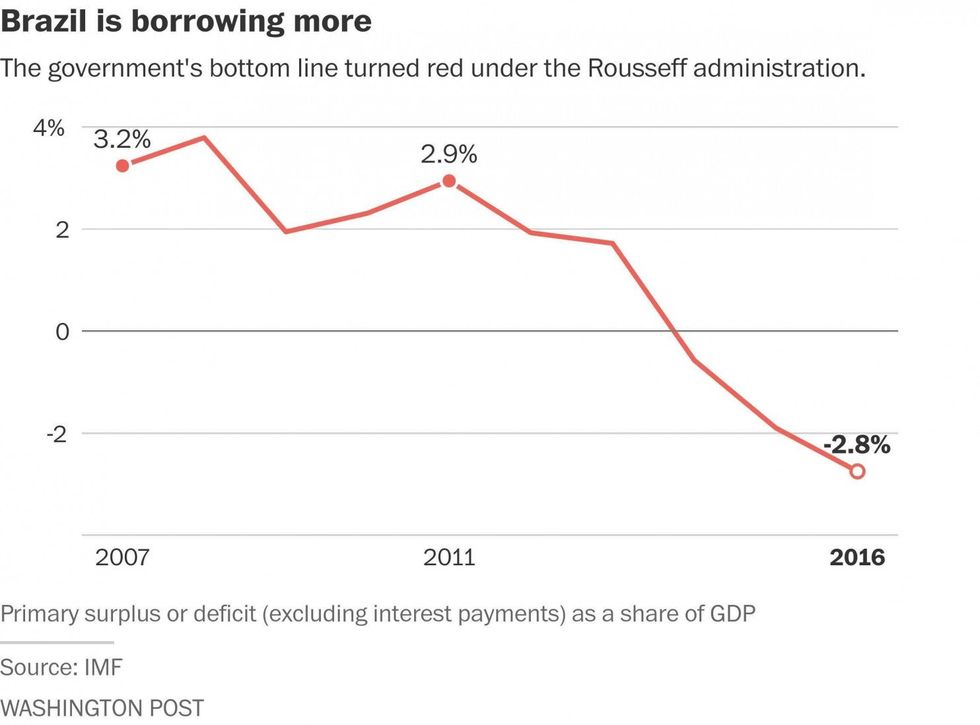

Under Lula, the Brazilian government's revenue exceeded new spending (excluding payments on interest) by about 3 percent a year. The government's finances have reversed under Rousseff, with spending exceeding revenue. Fitch, Moody's and Standard & Poor's now rate Brazil's debt as junk, indicating that investors who have loaned the government money might not be paid back.

Lula and Rousseff also favored local labor and domestically produced goods and services by, for instance, requiring companies bidding for fossil-fuel rights to rely on equipment manufactured in Brazil.

Last year, Rousseff announced $64 billion in new infrastructure expenditures. While few projects came to fruition, her plan, like the one Trump's economic advisers put forward last month, depended on collaboration with the private sector to provide financing.

The Brazilian left praises Rousseff for her efforts on behalf of organised labour and her ambitious programs to reduce poverty. De Bolle, however, argues that the Rousseff administration's policies for major Brazilian firms and manufacturers were more significant economically.

“The fact is that the Dilma government was much more generous to the rich than it was to the poor,” de Bolle says, calling Rousseff's approach “very Trump-like.”

She and other observers say that the combination of deficits and protectionist policy combined with the decline in prices for Brazil's exports to produce a serious slump.

Protectionist rules may have restricted the supply of goods, raising costs for consumers. Meanwhile, the government's debts had put the country in a vulnerable position, with interest absorbing more of the economy.

These constraints might be less of a problem for the United States if Trump pursues similar policies. The U.S. economy is better diversified than Brazil's and less dependent on exports, so while the bust in commodities was a real problem for Brazil, the United States would be more resilient.

Additionally, investors around the world see the federal government as a dependable borrower, so Trump will have more capacity to issue Treasury bonds without forcing up interest rates.

Meanwhile, many economists argue that a modest increase in federal spending could stimulate the U.S. economy without causing excessive inflation. De Bolle describes “a scenario where a Trump administration is actually able to do a sensible fiscal expansion, something that is more in line with what the country needs right now, without that actually unhinging the fiscal accounts going forward in the way that populist policies usually do.”

For their part, Trump and his economic advisers have argued that their plans will not burden the federal budget, promising that new investments in infrastructure and tax relief will be balanced by reductions in spending on other programs.

Whether investors believe this promise is unclear from the turmoil in bond markets since the election. They are demanding greater payments in exchange for holding the federal government's debt.

Yields on 10-year and 30-year Treasury notes have skyrocketed roughly 40 basis points, or 0.4 percentage points, since the election. That could be because investors expect Trump's policies to benefit the economy and they would rather put their money in stocks and other securities that will be more profitable than Treasury bonds during a boom. It could also be that investors expect inflation will erode the value of the bonds they hold today and are demanding compensation.

De Bolle said those climbing yields spelled more trouble for Brazil. Costlier yields mean that the government will have to pay lenders more for new loans to make good on the debts it has already accumulated.

That will be a challenge for President Michel Temer, who took office after Rousseff was forced out amid a scandal. Her supporters argue that allegations of corruption against her were politically motivated, and that her impeachment trial and removal from office amounted to an undemocratic coup.

This post has been expanded to include Monica de Bolle's affiliation with the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Copyright: The Washington Post

Top 100

The Conversation (0)