News

Alasdair Lane

Jul 03, 2015

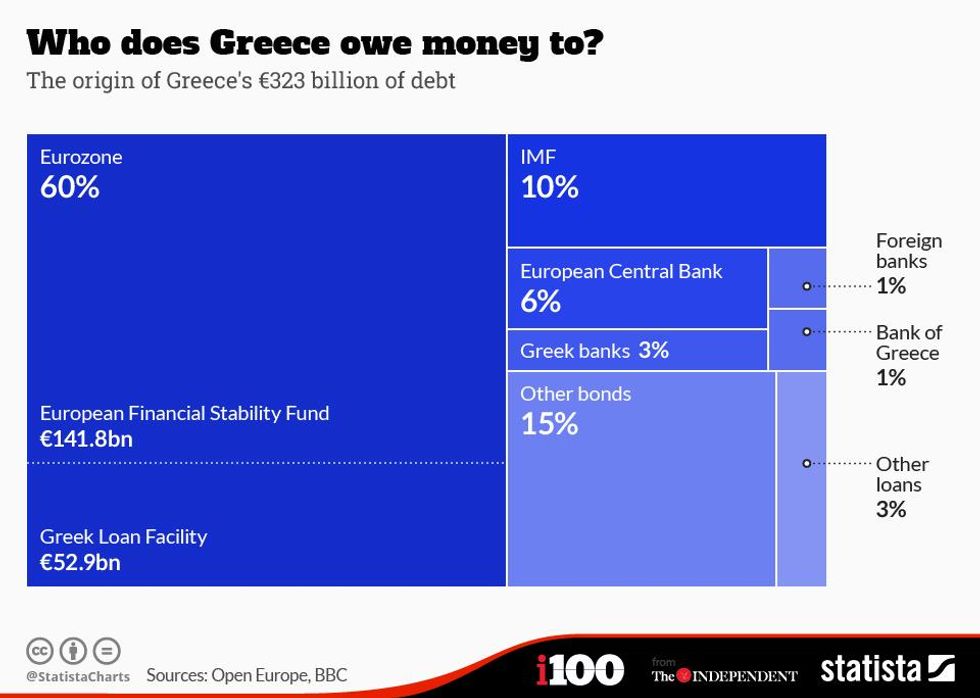

This was the week Greece made history by defaulting on its €1.55bn debt to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), becoming the first developed economy to miss a repayment.

Its banks closed, the Athens stock exchange was shut, and cash machine withdrawals were capped at €60.

A snap referendum was called by prime minister Alexis Tsipras to let the Greek people determine the country's fate – accept a bailout deal from their international creditors, or reject it in a move widely seen as a vote for Eurozone withdrawal.

Greek voters have a stark decision to make on Sunday, but their crisis is a murky one in which myths abound...

1. Grexit is now inevitable

Unable to repay its IMF debt, Greece is now in default – something which assures the country's exit from Europe. Or so it has been argued.

While the situation is perilously close to the point of no return, a Grexit is still not a sure thing.

From a legal standpoint, Greece's default does not entail automatic Eurozone expulsion. Addressing the European Parliament in April, Victor Constancio – VP of the European Central Bank (ECB) – said he was "convinced" a Greek exit would not result from a missed repayment, adding: "The treaty doesn't foresee that a country can be formally legally expelled from the euro."

However, a 'No' vote in Sunday's referendum on whether Greece should accept fresh bailout proposals would, it is widely believed, be the death knell for the country's Eurozone membership.

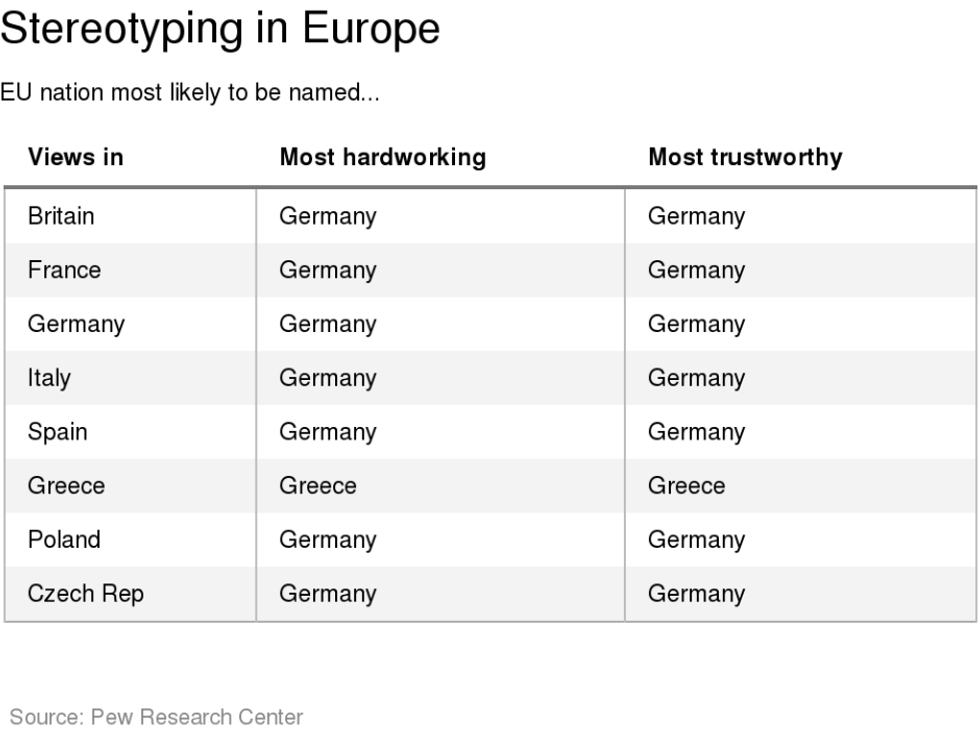

2. Greece alone is to blame for the debt crisis

It is easy to point the finger of blame in situations as desperate as this one, but it would be wrong to say Greece is solely responsible.

As vulnerable to market forces as any country in the world economy, Greece was crippled by the global financial meltdown in 2008. Fiscal mismanagement followed, veering the state toward bankruptcy.

While bailouts from the IMF – alongside the other Troika organisations – averted catastrophe in the short term, a series of dismal misjudgements made the default almost inevitable.

From failing to restructure Greek debt to its catastrophic imposition of public sector budget cuts, the IMF must bear a significant portion of the blame for the current situation. As put by The Independent's economics editor Ben Chu:

"It has been one of the biggest economic disasters since the Second World War."

3. Grexit will be catastrophic for Greece, as will its re-adoption of the drachma

Euroscepticism may be soaring at the moment, but it is conventional wisdom that Eurozone withdrawal would be an unmitigated disaster for the Greeks.

This may not be the case, however.

One of the easiest ways for a nation to gain international competiveness is to depreciate its currency – exactly what would happen if Greece readopts the Drachma. While expensive consumer items may become more expensive, food prices and the cost of other essentials could fall.

Eurozone expert Professor Stergios Skaperda has argued the financial benefits of a Grexit.

"Tailoring liquidity and exchange rate policy to the economy's needs and being responsive to levels of unemployment are some benefits that countries with their own currencies take for granted but are now sorely missed by Greece," he told i100.co.uk.

Departure from the euro could also boost Greece's democratic legitimacy and national sovereignty.

4. Eurozone countries will be hit hard if Greece leaves

Interconnected, interdependent – member states of the Eurozone currency union fear the waves of a Greek departure. These concerns are not unfounded, fiscal disruption is a near certainty if Greece does go it alone. It would, after all, be an unprecedented event – there is the risk of contagion, and even other countries following suit.

The euro may well be strengthened by a Greek withdrawal, however. As summarised by IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard:

"If it were to happen, I think the way to reassure markets and make progress is actually go further, use the opportunity to make progress in terms of the fiscal union and the political union. This would be clearly the right moment to do it."

In a Darwinian sense removing the weakest economy will consolidate the union's strength, and could increase its prosperity in the long-term.

5. Outside the Eurozone, Britain is sheltered from Grexit repercussions

It's the biggest external economic risk to the UK, chancellor George Osborne has warned of the crisis.

While Greek banks have only a tiny footprint in the UK economy, our exposure to the Eurozone as a whole is considerable. We are vulnerable, therefore, to any repercussions Grexit may have for the monetary union.

"The outlook has worsened," said Bank of England governor Mark Carney, speaking in the wake of Greece's default.

6. A Greek holiday is now impossible

In the throes of a worsening economic crisis, surely that Greek getaway is now off the cards?

Well no, actually.

Cash concerns are the obvious worry, but with a bit of preparation holidaymakers should be fine. As it stands, the €60 cap on cash machine withdrawals does not apply to international bank cards.

And if the country does leave the euro, the process will not be overnight. "We do not anticipate that there will be any need for tour operators to rebook their customers to a different destination," said an Association of British Travel Agents (ABTA) spokesperson, though the organisation does recommend those travelling to Greece take plenty of cash.

7. A referendum is the most democratic way forward

A national plebiscite on whether Greece should accept proposals made by its international creditors – in effect a referendum on the country's Eurozone membership – might seem like the most democratic solution to the crisis. This may not be the case, though.

Quite apart from the vague wording of the question – which critics argue is a government ploy to win the desired 'No' vote – there have been claims that the snap referendum falls short of international standards.

Guidelines drawn up by the Council of Europe (COE) recommend that voters have a minimum of two weeks before a national vote; PM Alexis Tsipras has given his citizens just nine days to make up their minds.

COE also recommends that its observers monitor the vote, something which will not happen on Sunday.

"This isn't possible [given the short notice] and the secretary general confirmed that the COE had not been asked to observe," said Council spokesman Daniel Holtgen.

8. Greece can recover without reform

Grexit or no Grexit, Greece has to change. A typically clientelist state – one in which material offerings are made for electoral support – allegations of bribery and political corruption have persisted throughout the Greek crisis. A bloated, inefficient public sector has hindered economic convalescence, critics argue.

For Professor Nicholas Economides, an international authority on network economics and public policy, internal restructuring is vital.

"For Greece to recover, [its public sector] needs to be cut drastically. Unfortunately civil servants are the backbone of Syriza and therefore the present government is totally against reducing the size of the state sector," he told i100.co.uk.

9. Things can't get worse for Greece

Sadly, they can. Things will almost certainly get worse before they get better. The gravity of the crisis should not be underestimated – the road to recovery, be it within the Eurozone or outside it, will be a long one indeed.

More: A man is trying to crowdfund €1.6bn to bail out Greece and wants your help

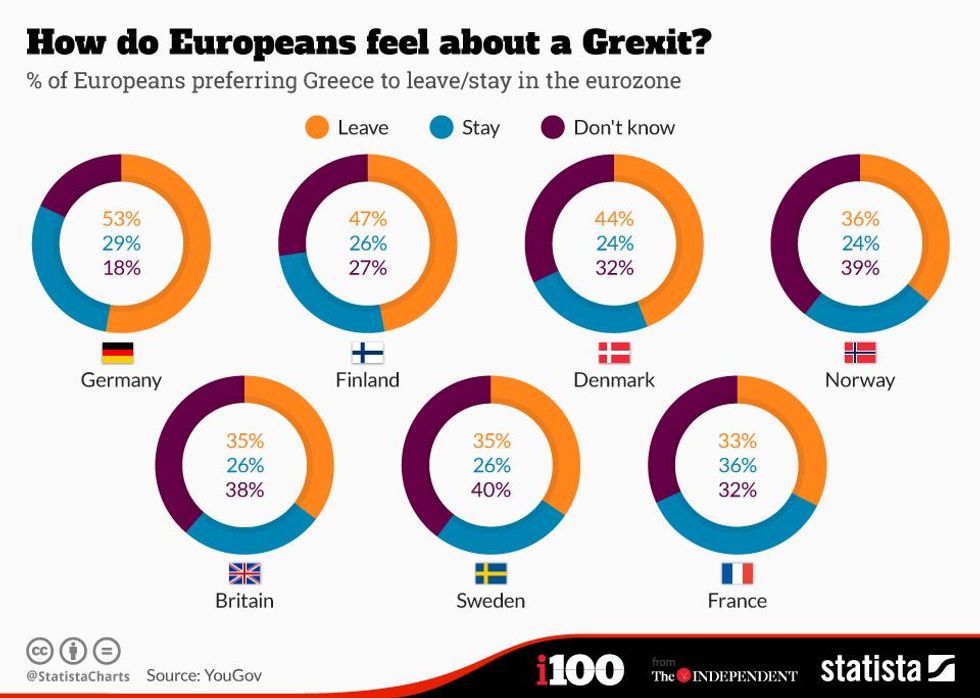

More: Most people don't care very much if Greece leaves the eurozone

Top 100

The Conversation (0)