Liam O'Dell

Sep 19, 2021

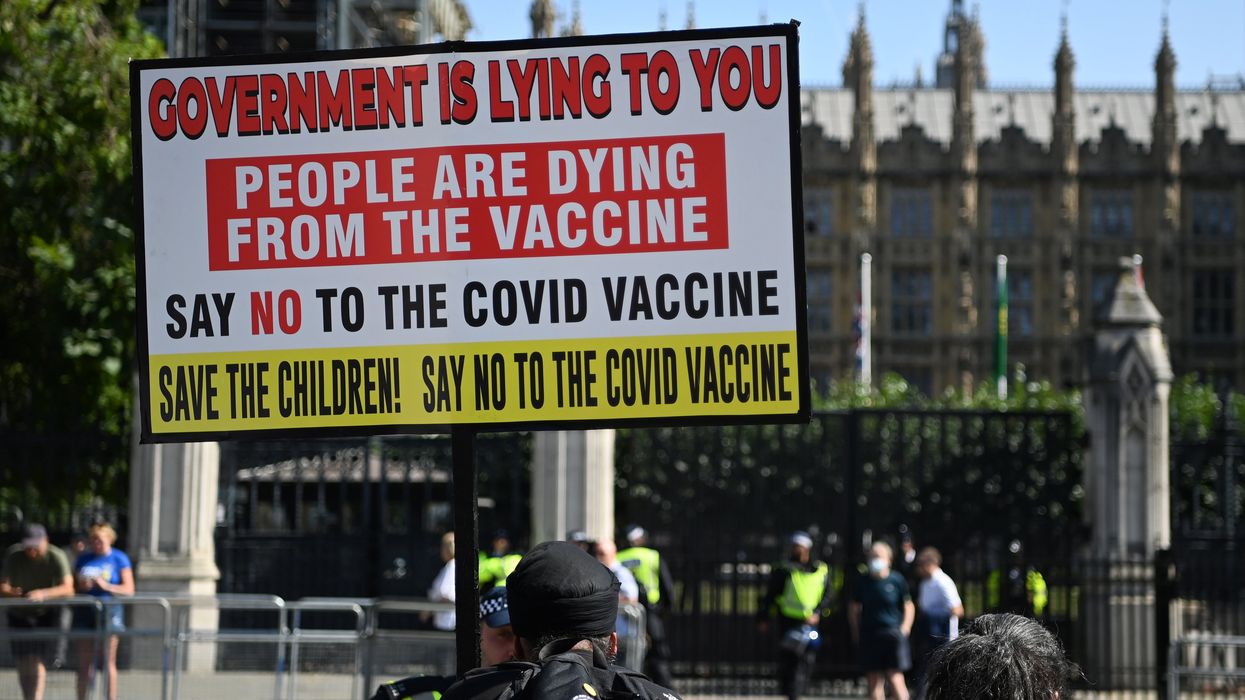

With the ongoing conspiracy theories being thrown around the coronavirus vaccines, some may well think that the anti-vax movement is a fairly recent phenomenon. Yet, the truth is that it’s anything but.

Before Piers Corbyn, David Icke and others, there was Andrew Wakefield, whose concerns around one vaccine, in particular, many believe, sparked years of anti-vax messaging and vaccine hesitancy.

Despite numerous scientists and medical professionals stressing the efficacy and safety of vaccines, unsubstantiated and disproven fears around getting one of the current coronavirus jabs, range from the misconception that they cause autism, to the view that Bill Gates is behind a plan to implant microchips into people – a claim without evidence that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has dismissed as “false”.

And if it isn’t an unfounded conspiracy theory that supposedly backs up their view, then an anti-vaxxer may well cite the argument that it’s “my body, my choice” – a phrase taken from the pro-choice movement when making the case for abortion.

This argument isn’t unfamiliar though, as concerns over bodily autonomy and vaccines were raised as far back as the 1800s…

The Vaccination Act

When a law was introduced in 1853 for all newborn children to be vaccinated against smallpox, with fines for parents who failed to comply, concerns were not only raised over making vaccines mandatory but also around their safety and impact.

In an article on anti-vaccination leagues in the 1800s, published in 1984, Stanley Williamson wrote: “By [1864-1868], however, severe and sometimes fatal side effects of vaccination were being reported, and with the outbreak of epidemics in various places in the early 1870s, which threw doubts on its efficacy, a campaign of opposition to the operation, on both medical and ethical grounds, began to grow.

“Leicester was one of the many towns in which Anti-Vaccination Leagues sprang up, demanding repeal of the compulsory clause in the Act, and advocating other measures for dealing with the disease, such as total isolation of patients and of anyone who had come into contact with them.”

Williamson’s article then goes on to quote from reports in the Leicester media, including one which refers to a crowd of protestors as “anti-vaccinators”.

Another report, from 1884, reads: “George Banford had a child born in 1868. It was vaccinated and after the operation, the child was covered with sores, and it was some considerable time before it was able to leave the house.

“Again Mr Banford complied with the law in 1870. This child was vaccinated … In that case erysipelas set in, and the child was on a bed of sickness for some time.

“In the third case the child was born in 1872, and soon after vaccination, erysipelas set in and it took such a bad course that at the expiration of 14 days the child died.”

In 1896, such a strong negative reaction from some to mandatory vaccination was noted by ‘the Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the subject of vaccination’ in their final report.

“It is impossible to leave out of sight the effect that such an extension of the present compulsory law might have in intensifying hostility, where it at present exists, and even in extending its area.

“Though if our recommendations, especially that which exempts from penalty those who honestly object to the practice, were adopted this objection would be much diminished,” they said.

Concerns over the whooping cough vaccine in the 1970s

The anti-vaccination leagues of the 19th century weren’t the only group to surface in response to fears around inoculations. Fast forward to the 1970s, and a group of parents had joined forces to raise concerns over the safety of a vaccine against pertussis – also known as ‘whooping cough’.

In a piece by Dr Gareth Millward of the University of Warwick in 2016, when he was a research fellow at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the academic wrote: “A letter to The Guardian by Drs J. V. T. Gosling and J. H. Moseley alleged that the pertussis vaccine was not effective enough to be worth administering. They also made reference to some cases of brain damage that might be linked to its use.

“This was pressed further in 1974 by Wilson and colleagues at Great Ormond Street Hospital, who alleged a link between brain-damaged children and the whooping cough vaccine.”

Dr Millward went on to cite concerns at the time that doctors would be involved in another public scandal similar to the use of thalidomide to treat morning sickness in pregnant mothers – which reportedly killed an estimated 80,000 babies worldwide and maimed 20,000 – between 1958 and 1962.

In 1974, Dr John Wilson and colleagues at Great Ormond Street Hospital alleged a link between the pertussis vaccine and encephalopathy – a form of brain damage.

Dr Millward, in his article, explained that reports such as those from Dr Wilson led the Association of Vaccine Damaged Children – a group “formed in 1973 by two mothers who blamed their children’s brain damage on the polio-myelitis vaccine” – to make a “tactical decision” to focus on pertussis and the vaccine designed to prevent it.

“Not only did many of its members (around two-thirds) blame the vaccine for their children’s injuries, there was a growing literature that suggested that there was hard evidence for their case,” he said.

However, allegations of a link between the vaccine and encephalopathy have since been contested by other medical experts. Dr Gerald S Golden, from the University of Tennessee, wrote in 1990: “A syndrome of pertussis vaccine encephalopathy was first reported 56 years ago. Analysis of the recent literature, however, does not support the existence of such a syndrome.

“There clearly is an increased risk of a convulsion after diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunization but no evidence that this produces brain injury or is a forerunner of epilepsy. Studies have also not linked immunization with either sudden infant death syndrome or infantile spasms.”

Nevertheless, the damage - at the time - had been done. An article from the British Medical Journal in 1981 reported that vaccination rates for the pertussis vaccine fell from around 80 per cent to 31 per cent. In some parts of the country, they said, rates had dropped as low as 9 per cent.

Furthermore, a Vaccine Damage Payments Act was introduced in 1979 which stated that if the government is satisfied “that a person is, or was immediately before his death, severely disabled as a result of vaccination” against a number of diseases listed in the Act, he would “make a payment of £10,000 to or for the benefit of that person or to his personal representatives”.

The full list included diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough (pertussis), poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, tuberculosis and smallpox – plus “any other disease” the government wanted to add through a statutory instrument.

This wouldn’t be the first time that a doctor’s disputed concerns over a vaccine would have a devastating impact on inoculation…

Andrew Wakefield and the MMR Vaccine

When discussing the development of vaccine hesitancy in the UK, it usually doesn’t take long before the name Andrew Wakefield is mentioned.

Once a doctor before he was struck off, Wakefield alleged in a 1998 paper that a vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella – known as the MMR vaccine – caused autism in children. If you were to read The Lancet paper now, you’d see it has the word ‘redacted’ plastered all over it.

Because it’s nonsense – to put it in the politest possible terms.

In the paper, Wakefield claimed: “Onset of behavioural symptoms was associated, by the parents, with measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination in eight of the 12 children, with measles infection in one child, and otitis media in another.

“Behavioural disorders included autism (nine), disintegrative psychosis (one), and possible postviral or vaccinal encephalitis (two).”

However, revelations by Sunday Times journalist Brian Deer found that with the study at least, “nearly all the children (aged between 2½ and 9½) had been pre-selected through MMR campaign groups, and that, at the time of their admission, most of their parents were clients and contacts of the lawyer, Barr”.

Who is this Barr, you ask? That would be Richard Barr, who, Deer discovered, had paid Wakefield more than £435,000 to help him with a lawsuit against vaccine producers.

“The goal was to find evidence of what the two men claimed to be a ‘new syndrome’, intended to be the centrepiece of (later failed) litigation on behalf of an eventual 1,600 British families, recruited through media stories. This publicly undisclosed role for Wakefield created the grossest conflict of interest,” Deer wrote on his website.

One claim proven in a professional conduct hearing by the General Medical Council included the fact that Wakefield carried out a study involving “invasive gastrointestinal and neurological tests” on children without ethics committee approval.

Deer also found that Wakefield had filed a patent for his own MMR vaccine in 1997, which the reporter described as a “shocking conflict of interest”.

It’s also worth mentioning the “ableist” implication that choosing not to get the MMR vaccine for the unsubstantiated fear of your child developing autism creates – as autistic advocates have stressed online:

All of this evidence and more would eventually come out to demonstrate that Wakefield’s claims were rubbish, but the damage had been – and continues to be – done.

According to BBC Bitesize, in 2018 the vaccination rate for the MMR vaccine had dropped to 87 per cent - eight percentage points below its target rate.

More recently, the latest meeting of the Joint Committee on Immunisation and Vaccination (JCVI) reported a 2 per cent fall in MMR vaccinations during the first coronavirus lockdown last year.

“The committee noted a concerning decline in uptake of the first MMR dose, which could lead to a big buildup of susceptibles in the longer term if this continued,” said the committee’s June minutes – only released on 20th August.

As for Wakefield, he’s continuing to raise concerns over vaccination – now with regards to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Washington Post reports that during a teleconference in May 2020, Wakefield said: “One of the main tenets of the marketing of mandatory vaccination has been fear. And never have we seen fear exploited in the way that we do now with the coronavirus infection.

“I think what we have reached is a situation where — I hope we’ve reached a situation where — the public are now sufficiently sceptical.

“We are seeing a destruction of the economy, a destruction of people and families … and unprecedented violations of health freedom. And it’s all based upon a fallacy.”

The real fallacy though, as scientists and media reports have shown, is in the anti-vaxxers’ arguments, and the consequences not only damage public confidence but can also cost lives.

Misinformation kills

Earlier this year a radio host in Florida who branded himself “Mr Anti-Vax”, died from Covid-19.

Last month, a nurse issued a warning after her anti-vaxxer mother, Geraldine Mount, died of Covid-19 aged just 57.

In July, Leslie Lawrenson, a 58-year-old man from Bournemouth, died at his home after he rejected the vaccine, downplayed his Covid symptoms and refused to go to a hospital. Nine days prior to his death, he had said the virus was “nothing to be afraid of”.

In some instances, it’s been reported that anti-vaxxers have changed their minds in hospital and asked for the vaccine while ill from the disease. Tragically, they could not be given the jab, as it works by helping an individual’s immune system recognise the virus to stop them from getting infected with it.

“Vaccines are not acute treatments of the disease. It takes the body time before the immune response is built up, including the fact that more than one vaccination may be needed to attain the immunity,” Dr Theodore Strange told Healthline.

Therefore, it’s best to get your vaccination as soon as possible.

How to respond to an anti-vaxxer

But when it comes to those cemented in their view that a vaccine is harmful, it can feel difficult finding a way to change that perception. However, there are ways to challenge an anti-vaxxer with a method that does not provoke a negative response.

On their website, the Meningitis Research Foundation offers the following message to send to anti-vaxxer friends and family: “Hello. I can understand why you might have some concerns about vaccines as there is a lot of misinformation online, and it can be hard to know who to trust.

“I’m very passionate about this issue and would encourage you to do some further reading before sharing these sorts of things. Vaccines have been around for a long time, and have proven to be one of the safest and most effective public health interventions in history.

“They save millions of lives every year. You can find lots of information about how vaccines work from these trusted sources of vaccine information:

- https://vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/vk/

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/why-vaccination-is-safe-and-important/

- https://www.who.int/topics/vaccines/en/

“It’s important to remember that not everyone will be amenable to this type of response. Many ‘anti-vaxxers’ will have been convinced by popular conspiracy theories or ‘fake news’ and it is not easy to convince them otherwise.

“The best thing that you can do to help slow the spread of misinformation, as well as protect your own mental health, is to present a civil response. Leave some reliable information for anyone else reading the thread and then avoid further responses,” they went on to add.

The webpage concludes by saying that they can offer help to those with questions about vaccines. Their support team can be contacted on 080 8800 3344, or by email: [email protected].

We’d also recommend visiting the NHS website for more on why the coronavirus vaccines are safe and effective.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)