News

Indy100 Staff

Aug 07, 2014

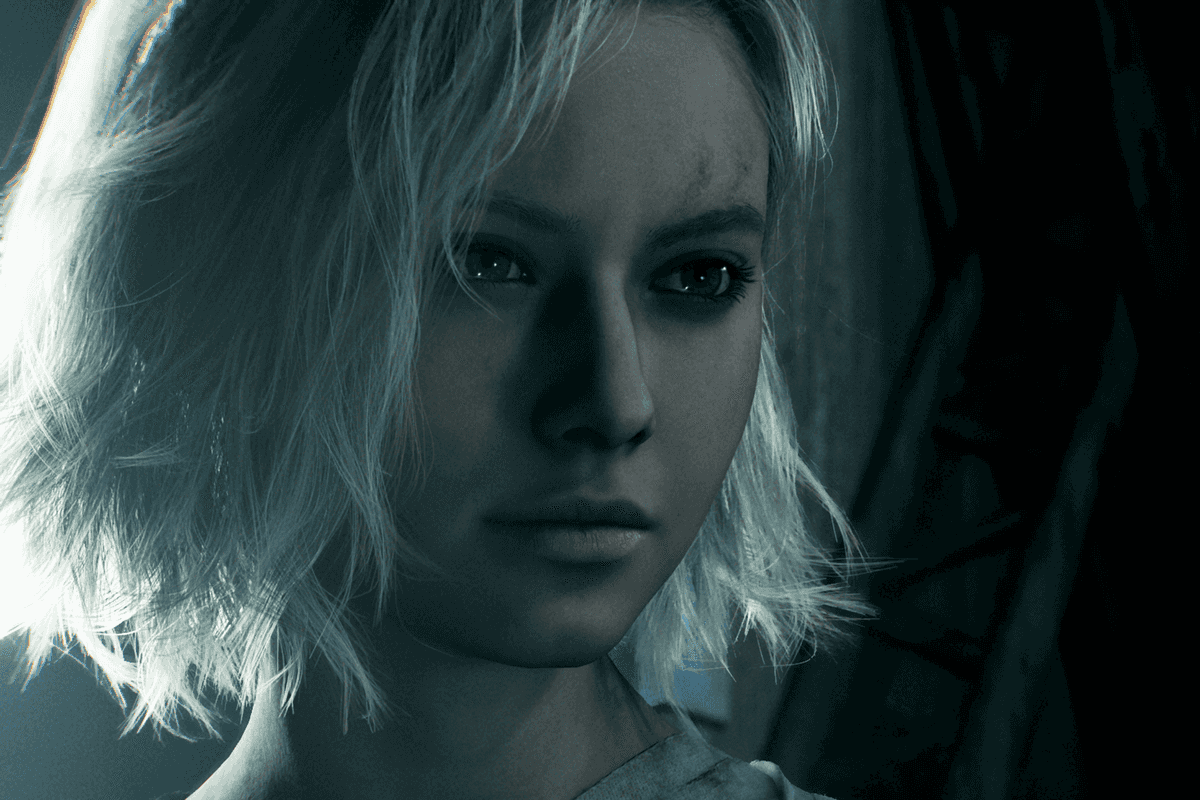

Khieu Samphan (L) and Nuon Chea

Two leaders of the Khmer Rouge were sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity by a UN-backed tribunal today - three and a half decades after the fall of the Cambodian regime which left close to two million dead.

The historic verdicts were announced against Nuoon Chea and Khieu Samphan, the only two surviving leaders of the regime left to stand trial.

Who are Nuoon Chea and Khieu Samphan?

Khieu Samphan was the regime's 83-year-old former head of state, and Nuon Chea was its 88-year-old chief ideologue. When the verdict was announced Nuon Chea said he was too weak to stand from his wheelchair and was allowed to remain seated. Because of the advanced age and poor health of the defendants, the case against them was divided into separate smaller trials in an effort to render justice before they die. Both men now face a second trial that is due to start in September or October, this time on charges of genocide.

What has this trial convicted them of?

Crimes against humanity. The tribunal’s judge Nil Noon said they were guilty of "extermination encompassing murder, political persecution, and other inhumane acts comprising forced transfer, enforced disappearances and attacks against human dignity".

There was no visible reaction from either of the accused at the verdict. Both have denied wrongdoing.

Who were the Khmer Rouge?

The Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia from 1975-79. Led by Pol Pot, nearly a quarter of the population - about 1.7 million people - died under its rule through a combination of starvation, medical neglect, overwork and execution. The case against Nuoon Chea and Khieu Samphan, covering the forced exodus of millions of people from Cambodia's towns and cities and a mass killing, is just part of the Cambodian story.

What was the reaction of survivors of the regime?

Survivors of the regime travelled from across the country to witness the trial. After the verdict many said they felt mixed reactions and questioned if any punishment could fit the crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge.

"The crimes are huge, and just sentencing them to life in jail is not fair," said 54-year-old Chea Sophon, who spent years in hard labor camps building dams and working in rice fields. His brother was killed during the Khmer Rouge era. He added: "Even if they die many times over, it would not be enough."

A female survivor, 58-year-old Khuth Vouern, said she felt a sense of relief that justice was finally served, even if it was generations late. "I have been waiting for this day for many years," said the woman, whose husband and several other family members were killed during the Khmer rouge reign. "Now, for the first time, my mind feels at least some degree of peace."

What about the authorities?

Tribunal spokesman Lars Olsen called it "a historic day for both the Cambodian people and the court. The victims have waited 35 years for legal accountability, and now that the tribunal has rendered a judgment, it is a clear milestone".

Many have criticized the slow justice, however, and its cost.

The UN-backed tribunal, formally known as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia and comprising of Cambodian and international jurists, began operations in 2006. It has since spent more than $200 million, yet it had convicted only one defendant - prison director Kaing Guek Eav, who was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2011. The current trial began in 2011 with four senior Khmer Rouge leaders; only two remain. Former Foreign Minister Ieng Sary died in 2013, while his wife, Social Affairs Minister Ieng Thirith, was deemed unfit to stand trial due to dementia in 2012. The group's top leader, Pol Pot, died in 1998.

Amnesty International called the verdict "a crucial step toward justice". But it also noted several "troubling" obstacles the tribunal faced - including the refusal of senior Cambodian government officials to give evidence and allegations of political interference. It called for the remaining cases to be completed "in a timely and fair manner without political interference".

Top 100

The Conversation (0)