News

Louis Dor

Mar 16, 2016

Picture: Stefan Rousseau - WPA Pool/Getty Images

The Government is set to announce legislation to turn every school in England into an Academy by 2020, it has been reported.

In Wednesday's Budget, George Osborne will unveil the plan, according to the Guardian, as described in the Conservatives' election manifesto in 2015.

The academy programme began under New Labour, but it was legislation passed under the Coalition government, when Michael Gove was education secretary, that enabled all schools to convert to an academy.

The newest legislation will mean all schools will be forced to become academies, given jurisdiction over their own budgets, curriculum, staff, term times and timetables, whether they want this autonomy or not.

Here are some of the hurdles faced:

1. They're unpopular

A poll of parents conducted in September 2015 by the PTA UK found that 97 per cent would like to be asked before a school is turned into an academy.

If it's announced, you were asked at the election, apparently.

In addition, polling by ICM in 2014 found that 57 per cent of people oppose academies, compared to 32 per cent who support them.

2. They don't even necessarily work

Assessment of their performance is tricky, given the fact that academy chains tend to take on local authority schools that are performing poorly.

A Ofsted analysis showed that many academies were performing worse than other local authority schools, while a Sutton Trust report in 2014 warned that they were worse for disadvantaged pupils.

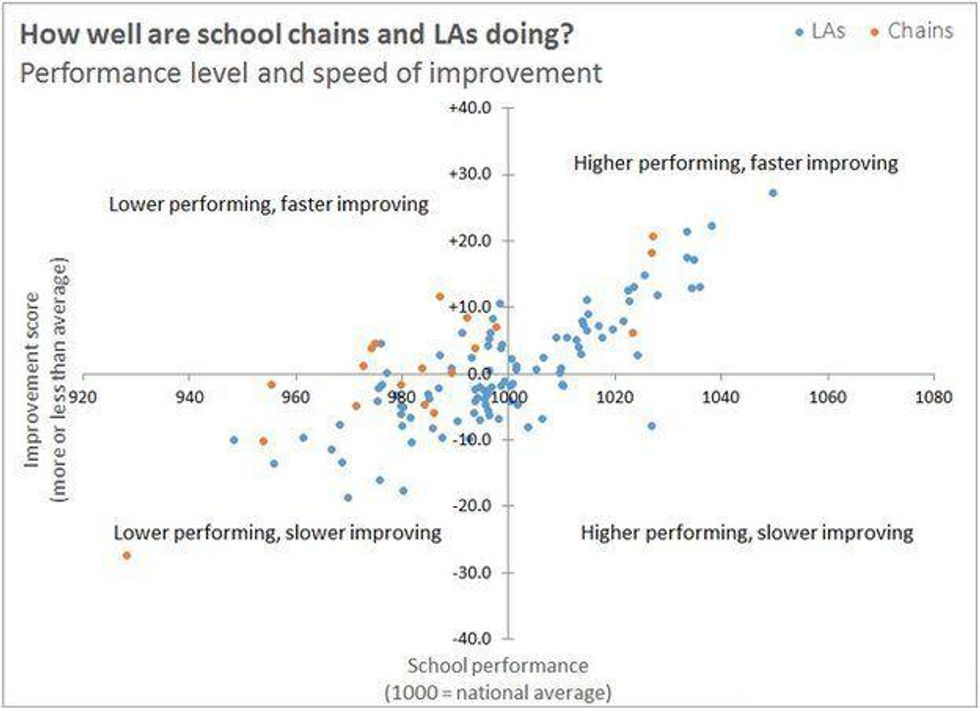

In addition, the Department for Education created metrics last year that sought to compare performance of some chains against equivalent local authority schools, balancing a "value-added" performance score for academies with a gauge for capacity to improve.

It looked something like this:

Generally academies have prospered in London but have experienced difficulty in other areas, with the University of Chester Academy Trust academy chain performing exceptionally poorly.

The picture overall is that academies don't automatically offer a benefit.

3. It means a lot more work for the Department for Education and less local accountability

While academies will be allowed certain freedom, and supporters say bureaucracy is cut, teachers' unions say the policy ultimately leads to the privatisation of state schools, run by sponsor-led chains.

Kevin Courtney, the deputy general secretary of the National Union of Teachers, said:

The fig leaf of ‘parental choice’, ‘school autonomy’ and ‘raising standards’ has finally been dropped and the government’s real agenda has been laid bare – all schools removed from collaborative structures within a local authority family of schools, all schools instead run by remote academy trusts, unaccountable to parents, staff or local communities.

In addition the Department for Education would control the funding of all the new academies centrally, as opposed to the local authorities. This means a lot more work for Whitehall, which has gone from being an overarching strategic body to deciding rules for individual skills.

4. Councils would be angry

The move would effectively rob local authorities of control over local schools.

Councillor Roy Perry, chairman of the Local Government Association’s children and young people board, told the Guardian:

Ofsted has rated 82 per cent of council-maintained schools as good or outstanding, so it defies reason that councils are being portrayed as barriers to improvement. Ofsted has not only identified that improvement in secondary schools – most of which are academies – has stalled, but it has praised strong improvement in primary schools, most of which are maintained.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)