As the world becomes more and more of a nightmare, with an impending climate catastrophe and negative news arriving via push notification every other hour, people have turned to an unorthodox escape method: true-crime stories.

Since the podcast Serial launched our true-crime obsession into overdrive in 2014, we’ve been getting to know convicted murderers from the safety of our homes. Are they really guilty? And what would we have done in their position?

Making the perfect true crime show is a fine art and constantly producing content that’s addictive and compelling a big ask. If we’re really honest, the genre was starting to feel a slightly predictable (please don’t @ us).

But in a noticeable shift from normal proceedings, true crime shows are now reintroducing us to a particularly deadly protagonist: the gay serial killer.

Ryan Murphy’s The Assassination of Gianni Versace followed gay serial killer Andrew Cunanan as he pursued fame, love and money, killing anyone who crossed his path. Netflix docu-series Don’t F**k With Cats gave viewers an insight into the twisted mind of Canadian murderer Luka Magnotta. Later this year, The Barking Murders, a three-part drama starring Sheridan Smith and Stephen Merchant, will explore the crimes of the so-called "Grindr killer" Stephen Port, who murdered at least four men.

Tentative queer readings of murderous protagonists in films from decades gone by, such as We Need to Talk About Kevin, Kill Bill and several Bond villains who have flirted with homoeroticism (the most brazen example being Javier Bardem in Skyfall), have opened the door to the killers of today who are explicitly and unavoidably gay. The renewed interest in gay killers can be seen as a continuation of pop culture’s preoccupation with “gay death” – it’s just now we’re doing the killing as well as being killed.

Killing Eve brings murderous queer women to the forefront too. The BBC America drama stars Jodie Corner as a murderous queer assassin, while Sandra Oh portrays an MI5 agent whose flirtations with same-gender desire run parallel to her darkest impulses. It’s an undeniably more nuanced depiction than the film Basic Instinct (1992), starring Sharon Stone, which was strongly opposed by LGBTQ+ rights activists, who criticised the film's depiction of gay relationships and the portrayal of a bisexual woman as a murderous psychopath. Don’t F**k With Cats actually theorises that Stone’s character in Basic Instinct was one of Canadian serial killer Luka Magnotta’s main inspirations, which indicates it wasn’t the most responsible depiction of same-sex attraction and murder.

The “digital revolution” has provided infinite ways – from podcasts to Pinterest – of discovering queer heroes. Films starring gay heroines in particular – from LGBTQ+ rights pioneer Harvey Milk (Milk), to music icon Elton John (Rocketman) and British codebreaker Alan Turing (The Imitation Game) – are now part of Hollywood’s filmic furniture. But Huw Lemmey, co-host of Bad Gays – a podcast about “evil/complicated gays” throughout history – thinks that the stories of gay men who have been considered “bad” in the past are just as important.

These men can teach us how homosexuality and gender variance were once understood, but also how the modern ideas around gay men came to be. Lemmey suggests that pop-culture’s sudden attraction to very “bad” killer gays might be a reaction to protagonists who are increasingly pedestrian. “As gay rights have advanced in the past few decades, a very particular type of usually white gay male representation of gays has been adopted and integrated by a wider society,” he says. “For many this sort of neutered, polite assimilation was never an aim or aspiration, and antiheroes can reflect that.”

The origins of the “gay killer”

Seán McGovern, head of programming at GAZE – Dublin’s International LGBT Film Festival – tells indy100 that gay characters have historically been defined in a narrow set of tropes. He mentions “the sad homosexual” or “the sissy” as the primary depictions of gay men in pop culture. Think: Ennis and Jack Brokeback Mountain (2006) or flamboyant control-room worker Johnny in Airplane! (1980).

There is also a history of conspicuously ignoring a character’s sexual identity, while portraying them in such a way that audiences are likely to assume they are gay - particularly if we aren’t supposed to like them. The connection between traits which are perceived as stereotypically gay and the idea of “evil” can even be seen in Disney films, where villains – such as Scar (The Lion King) and Prince John (Robin Hood) – are coded as gay by combining “flamboyance” with wickedness.

In terms of films “for adults”, McGovern points to Alfred Hitchcock’a Rope (1948) as a game-changer. “Rope was a seminal turning point from pathetic to pathological,” he says. “The protagonists are coded homosexual killers, transgressing against all that is decent by killing for fun.”

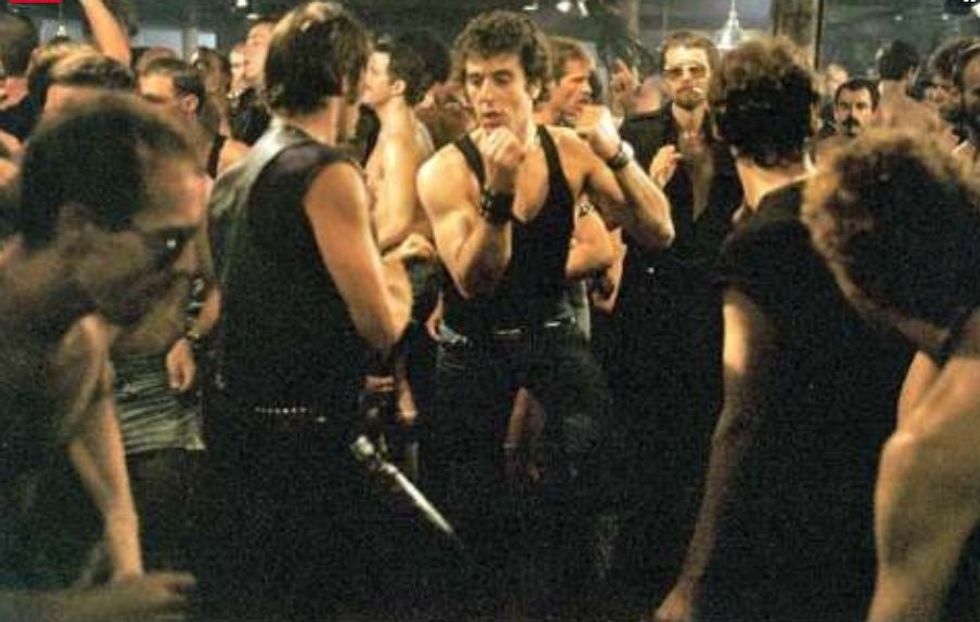

Three decades later, American erotic crime thriller Cruising (1980), which followed a serial killer targeting gay men in the leather scene in the late 1970s, became one of the earliest examples of a gay killer who wasn’t just coded or inferred to be gay but actually explicitly so. Cruising was protested by gay advocacy groups at the time, mostly on the grounds that it was made by straight people, for straight people and exploited the community for profit. McGovern explains:

“Cruising introduced gay men to a mass audience. But it definitely didn’t help that it was in the form of the S&M leather scene. In the quest for a queer killing psychopathic murderer, queers went from near invisibility to explicit, hanky code, sex-club scrutiny.”

Cruising was released at a time when the “gay panic” defence – a legal strategy in which a straight defendant can claim diminished responsibility or innocence for violent crimes if they feared unwanted advances from someone of the same gender – had been successfully used in a string of high-profile murders of gay men in the US. Soon after this, the threat of Aids further underlined the link between gay men and death (and as de facto “killers”) in public consciousness.

“The mere act of gay sex became fatal,” says McGovern. “A threat to ordinary, law abiding heterosexual families, the homosexual became a danger far beyond what was known about the disease.”

Pop culture further reflects this narrative. Films, plays and TV shows documenting the Aids crisis – from Dallas Buyers Club and Philadelphia to The Inheritance – all have one element in common: endings marred by death. In 2018, film critic Benjamin Lee lamented that so much of LGBTQ+ cinema has an over-reliance on gay death and “bleakness”. He’s not the only one to notice this, either: writing in the Guardian in 2013, James Rawson referred to this phenomenon as the “Sudden Gay Death Syndrome” in a discussion over the ending of A Single Man.

The undeniable (problematic) hotness of gay killers

Queer culture writer Jack King thinks that Ryan Murphy’s The Assassination of Gianni Versace exposes a long-held conflict between “wanting to be” and “wanting to fuck” gay villains. He observes that the killers we see on-screen aren’t too far away from how many gay men live their lives. “Most of the time – at least, in my experience – sexuality seems to be incidental to the impulse to kill,” he explains. “You might argue that gay dating apps, which are unique to the gay community (seeing as Tinder presents a lot more barriers than Grindr, Hornet and Scruff etc, where random, private meetups are normalised) present opportunity – we're living through a time where sex, and people, are more accessible than ever.”

Sex / Crime, a new play that recently debuted at London’s Soho Theatre, follows two gay men as they reimagine the murders committed by a gay serial killer. Playwright Alexis Gregory – creator and star of the show – tells me that it’s often impossible to untangle sex and murder. He says:

“When I told some gay men I was writing a play about gay serial killers, lots of them said ‘that’s hot’”

Gregory says the stories depicting gay killers and killings – such as the haunting finale of Russel T Davies drama Cucumber, where a closeted gay man beats a hook-up to death with a golf club – are so impactful because they reflect the dangers of gay life.

“Do we, as gay men, put ourselves into riskier situations than our straight counterparts? Inviting strangers into our homes, going back to theirs, the drug taking etc?” he asks. “I’m not naive enough to think straight people don’t indulge in such ‘risky’ behaviour, but perhaps two (or more) men coming together doesn’t come with the same possible threat or caution that a woman may feel.”

The importance of who tells these stories

Pop culture that explores real-life crimes, such as docu-series and dramas, allows us to indulge our fascination with the dark side of human nature while also reassuring ourselves that we’re upstanding moral citizens by comparison. But it’s curious that the vast majority of true crime docu-series and podcasts that platform straight people who’ve been convicted of crimes – most famously Netflix’s Making a Murder and Serial – approach their alleged perpetrators with a presumption of innocence, exploring the idea that justice wasn’t served. Gay killers, on the other hand, aren’t afforded the same luxury: they’re nearly always undebatably guilty.

One of Netflix’s most ambiguous and even-handed ventures into true crime, The Staircase, follows the story of novelist Michael Peterson, who was convicted of killing his wife. In a break with tradition, at the end of the story, many viewers still felt that Paterson was guilty. But it is no coincidence that his own bisexuality was a major theme, and bombshell, in the series. Bisexuality (and inferred homosexuality) was used by the prosecution to convince the jury – and Netflix viewers watching years later – of his guilt.

In Amanda Knox, we see how the Italian media constructed a narrative of lesbian lust to condemn the young American to guilt. We see this motif again in Netflix's Killer Inside: The mind of Aaron Hernandez, which tells the story of the NFL superstar who was accused of committing two murders. While the docu-series heavily implies that it was brain damage in the form of CTE which may have led him to commit the inexplicable crimes, it also goes out of its way to raise questions about his sexuality, with a teammate all but confirming that he was bisexual as a "twist" which the producers seem unable to get enough of. They are unable to provide any evidence to confirm this beyond hear-say, nor can they tell us that it had anything to do with the crimes themselves. The reason his presumed sexual identity is given such a prominent role in the story is essentially to add salaciousness to the story, something which was heavily criticised at the time. Time and time again, queerness is synonymous with deviance and death.

In the case of a show like American Crime Story’s Versace series – which was written and directed by Glee creator Ryan Murphy (who identifies as a gay man), and based on a true story – King thinks that Murphy doesn’t demonise his murderous protagonist. “Versace genuinely reaches for a measure of objectivity, in shining a light on Cunanan’s terrible upbringing. The show allows the spectator a measure of empathy for him,” he says.

It seems that this show, which was brought to the screen by a gay man, had a much more intricate approach to exploring any links between the protagonist’s sexuality and his murderous actions.

“Cunanan's impulses to kill feel less imposed by his sexuality than by the pressures of capitalism, and a society built upon a foundation of competition – to have the perfect lover, the perfect teeth; the best fashion sense. The latter is far more incidental, but still speaks to the heightened social pressure that gay men often feel.”

Why (straight) viewers love gay killers

Heterosexual audiences will always have some sort of reaction – ranging from revulsion to fascination and celebration – to queer culture and sex. But we know that there’s a long, ugly history of queer sexuality, particularly gay male stories, being sensationalised in the press. This is still going on: just look at gay rugby star Gareth Thomas’s decision to come out as HIV positive last year after his parents were allegedly door-stepped by a tabloid newspaper. Writer Jason Okundaye also noted that the online discourse surrounding YouTuber James Charles’s very public 2019 fall-out with influencer Tati Westbrook often veered into homophobia, tapping into the long history of depicting gay men as sexual predators.

The recent reporting of Normawati Sinaga – who was sentenced to life in prison this year after being found guilty of raping 48 men in Manchester – tells us that gay men committing the most reprehensible crimes drives horrified fascination (and views) like few other stories.

With regards to gay killer narratives in particular, Lemmey identifies differences in the way gay people and straight people tend to approach them.

“Gay people secretly wish for their own destruction. Whereas straight people secretly envy the unhinged libidinal urge of queer life.”

This is obviously a fairly extreme generalisation, but if this is the way social consciousness is functioning for a significant chunk of people it could help explain why different audiences seem so enamoured with these stories.

Are gay killers gay rights?

So are we still being exploited, just like we were with Cruising? Lemmey says that it's an issue of power.

“Control of the media has always allowed people to dictate what stories are told, and how. Those people are, and historically have always been, white, male, cis, straight and, of course, wealthy,” he says. “That means that people of colour and queer people have been either excluded totally from films, television and books, or been portrayed only through the eyes of people who don't really understand their lives or experiences. Often, those representations just compound the struggles those people have to face.”

Given what we know about the sensationalism of gay stories, it’s bleakly predictable that a gay killer renaissance would be the ~oh so scandalous~ next step in Hollywood’s obsession with murderers. After all, TV shows and films spotlighting straight male murderers – from Netflix’s You to 2019’s Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (the latest instalment in the problematic obsession with serial killer Ted Bundy) – still have disturbingly consistent popularity, but that can’t last forever.

It might be too early to tell whether pop-culture’s embrace of the openly gay serial killer is good or bad, but the answer likely hinges on who is bringing these stories to the screen and why. Yet factoring in the long, complicated history of the “gay killer”, and the homophobic association between homosexuality, predatory behaviour and death, it’s likely that the revival of this trope has more potential for oppression than liberation.

But don’t let that kill your buzz.

More: Gay men are in a hate-love relationship with Pete Buttigieg