Welsh pop singer Duffy wrote an open letter to Netflix, accusing the platform of glamorising sexual violence against women.

She has written an open letter to Reed Hastings, the head of Netflix, about 365 Days, a Polish film based on a book by Blanka Lipińska, about a woman who is kidnapped and given a month to fall in love with the head of a Sicilian mafia family. The film is categorised on Netflix as an “erotic drama”.

In the open letter, Duffy said:

'365 Days’ glamorizes the brutal reality of sex trafficking, kidnapping and rape. This should not be anyone’s idea of entertainment, nor should it be described as such, or be commercialised in this manner.

It grieves me that Netflix provides a platform for such ‘cinema’, that eroticises kidnapping and distorts sexual violence and trafficking as a “sexy” movie. I just can’t imagine how Netflix could overlook how careless, insensitive, and dangerous this is.

It has even prompted some young women, recently, to jovially ask Michele Morrone, the lead actor in the film, to kidnap them.

In February, Duffy wrote about an ordeal she had faced where she was kidnapped, drugged and raped after being held in a foreign country for close to a month.

After the incident, which happened almost a decade ago, she retreated from the public eye.

Duffy also says,

To anyone who may exclaim ‘it is just a movie’, it is not ‘just’, when it has great influence to distort a subject which is widely undiscussed, such as sex trafficking and kidnapping, by making the subject erotic.

Here's what she means:

Depictions of sexual violence against women on screen, particularly in recent years, have come under a lot of scrutiny.

Films and media featuring violence against women are fairly popular – and even par for the course in certain genres, such as in TV shows about crime and in horror films.

Classic films like Sixteen Candles have faced criticism in recent years – and at the time – for making "jokes" about sexual harassment and assault.

In one scene, the school hunk tells a nerd that his girlfriend is passed out in car and that he could do whatever he wanted to her. Later on in the film, the two are shown falling in love, even if it’s never clear if they do actually have sex.

Last year, The Nightingale, an Australian horror film directed by Jennifer Kent (who also directedThe Babadook) about a woman who sets out to find her attacker after being raped, was the subject of controversy after screenings saw people walking out and even calling the director a “whore”.

Game of Thrones was similarly often criticised for what critics called gratuitous rape scenes.

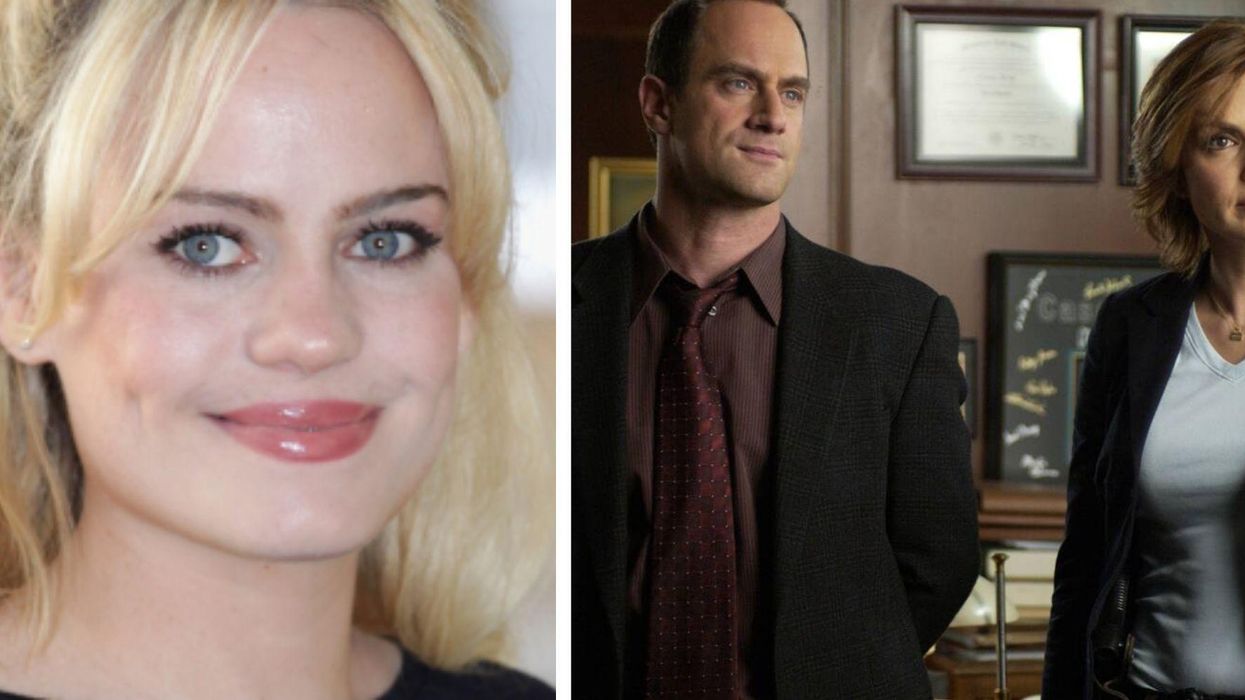

Law and Order: SVU has repeatedly come under fire for this in the past – particularly as the show is focused on the sexual crimes that women and children face.

However, recent years have seen the show’s depiction of sexual assault changing, and charities that work with survivors of sexual violence crediting the show for encouraging people to come forward about their experiences.

Can it be done right?

Unbelievable, a Netflix show based on a ProPublica article about women who were raped in the US, was credited for depicting the realities of what women face without resorting to scenes of sexual violence.

Similarly, In I May Destroy You, Michaela Coel deftly weaves together a story about sexual assault with the realities of sexual violence against women – that it’s all too common, and isn’t always perpetrated by strangers.

The tide on sexual violence in films may be turning.

A group of students at Cambridge University put together a database of sexual violence in films, called "Unconsenting Media" – which can help people check whether the films or TV shows that they’re watching have instances of sexual violence.

Then, there are also advocates like Duffy, who are pointing out that the industry has a responsibility to take these issues seriously.

She ends the letter with a reminder of what Maya Angelou told us a long time ago: “When we know better, let us do better.”