Jesse Jackson dead: Civil rights icon dies aged 84

The Independent/ Lumen5

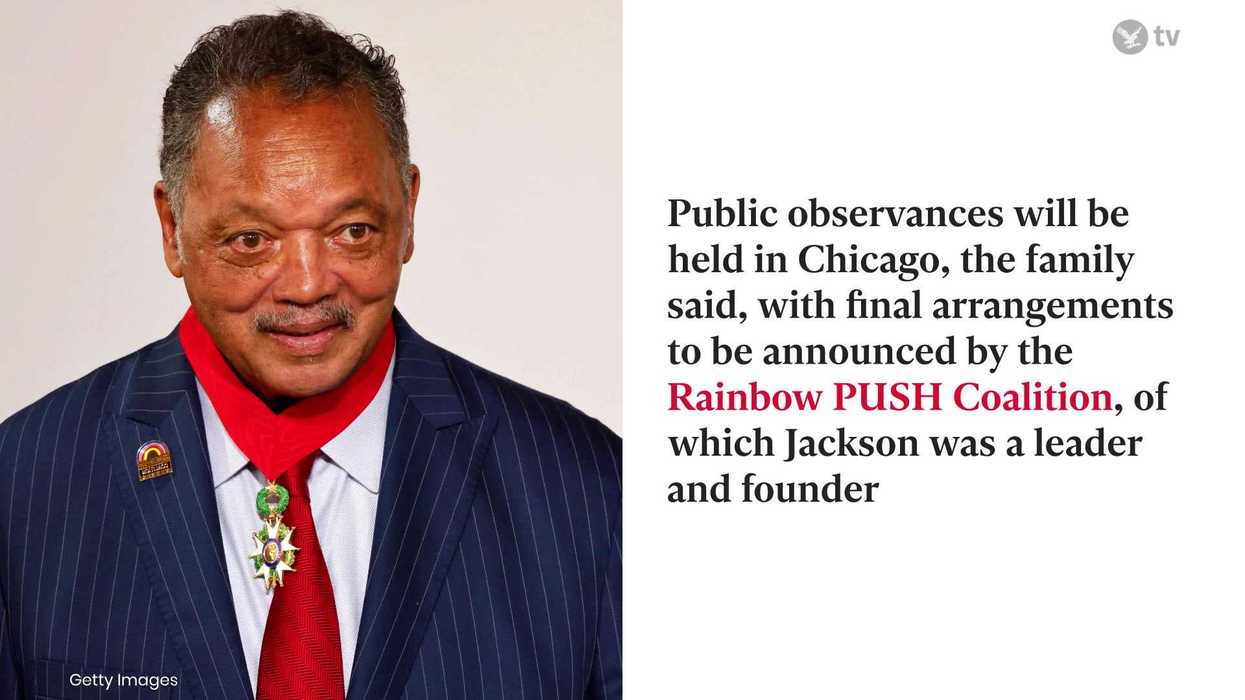

The Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, a towering figure in the American Civil Rights Movement and a two-time presidential candidate, has died at the age of 84. A protégé of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., Mr Jackson continued to lead the fight for civil rights for decades following Dr. King’s assassination.

As a young organiser in Chicago, Mr. Jackson was called to meet with Dr. King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis shortly before the civil rights leader was killed. He subsequently positioned himself as Dr. King’s successor, embarking on a lifetime of crusades both in the United States and abroad. He championed the poor and underrepresented, advocating on issues ranging from voting rights and job opportunities to education and healthcare.

Mr. Jackson achieved diplomatic victories with world leaders and, through his Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, channelled calls for Black pride and self-determination into corporate boardrooms, pressuring executives to foster a more open and equitable society in America. His powerful declaration, "I am Somebody," a line from a poem he frequently recited, resonated widely: "I may be poor, but I am Somebody; I may be young; but I am Somebody; I may be on welfare, but I am Somebody," he intoned. This message was deeply personal, as he rose from obscurity in the segregated South to become America’s most prominent civil rights activist since Dr. King.

His daughter, Santita Jackson, confirmed that her father passed away at home in Chicago, surrounded by his family. "Our father was a servant leader — not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world," the Jackson family stated online. "We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family." Fellow civil rights leader the Rev. Al Sharpton hailed his mentor as "a consequential and transformative leader who changed this nation and the world." Mr. Sharpton added on Facebook: "He kept the dream alive and taught young children from broken homes, like me, that we don’t have broken spirits. A giant has gone home."

Despite significant health challenges in his later years, including a rare neurological disorder that affected his movement and speech, Mr. Jackson remained active, protesting against racial injustice into the era of Black Lives Matter. In 2024, he appeared at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and a City Council meeting to support a resolution backing a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war. "Even if we win," he told marchers in Minneapolis before the officer responsible for George Floyd’s death was convicted, "it’s relief, not victory. They’re still killing our people. Stop the violence, save the children. Keep hope alive."

Mr. Jackson’s voice, infused with the stirring cadences of the Black church, commanded attention. On the campaign trail, he employed rhyming slogans such as "Hope not dope" and "If my mind can conceive it and my heart can believe it then I can achieve it," to deliver his messages. While he faced critics, some of whom considered him a grandstander, Mr. Jackson reflected on his legacy in 2011, telling The Associated Press: "A part of our life’s work was to tear down walls and build bridges, and in a half century of work, we’ve basically torn down walls. Sometimes when you tear down walls, you’re scarred by falling debris, but your mission is to open up holes so others behind you can run through." In his final months, receiving 24-hour care, he lost the ability to speak, communicating with family by holding and squeezing their hands. His son, Jesse Jackson Jr., told the AP in October, "I get very emotional knowing that these speeches belong to the ages now."

Born Jesse Louis Jackson on 8 October 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, to Helen Burns and Noah Louis Robinson, he was later adopted by Charles Henry Jackson. A talented athlete, he was a star quarterback in high school and initially accepted a football scholarship to the University of Illinois. After reportedly being told Black people could not play quarterback, he transferred to North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, where he excelled as a quarterback, an honour student in sociology and economics, and student body president. Arriving on the historically Black campus in 1960, shortly after students initiated sit-ins at a whites-only diner, Mr. Jackson quickly immersed himself in the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. By 1965, he joined Dr. King’s voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, and was later dispatched to Chicago to launch Operation Breadbasket, a Southern Christian Leadership Conference initiative to pressure companies into hiring Black workers. Mr. Jackson described his time with Dr. King as "a phenomenal four years of work."

Mr. Jackson was with Dr. King on 4 April 1968, when the civil rights leader was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Mr. Jackson’s account claimed Dr. King died in his arms. With a flair for the dramatic, he wore a turtleneck he said was stained with Dr. King’s blood for two days, including at a memorial service where he declared: "I come here with a heavy heart because on my chest is the stain of blood from Dr. King’s head." However, several of Dr. King’s aides questioned this account, noting a lack of photographic evidence of Mr. Jackson with blood on his clothing immediately after the assassination.

In 1971, Mr. Jackson broke from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to establish Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity). Based on Chicago’s South Side, the organisation pursued a broad mission, from diversifying workforces to registering voters in communities of colour. Through lawsuits and boycott threats, Mr. Jackson compelled major corporations to invest millions and publicly commit to diversifying their workforces. His constant campaigning often left his wife, Jacqueline Lavinia Brown, whom he married in 1963, to lead in raising their five children: Santita Jackson, Yusef DuBois Jackson, Jacqueline Lavinia Jackson Jr., and two future members of Congress, U.S. Rep. Jonathan Luther Jackson and Jesse L. Jackson Jr. The elder Mr. Jackson, ordained as a Baptist minister in 1968 and earning his Master of Divinity in 2000, also acknowledged fathering a child, Ashley Jackson, with an employee at Rainbow/PUSH, Karen L. Stanford, stating he supported her emotionally and financially.

Despite once telling a Black audience he would not run for president "because white people are incapable of appreciating me," Mr. Jackson ran twice, achieving greater success than any Black politician before Barack Obama. He won 13 primaries and caucuses for the Democratic nomination in 1988, four years after his first attempt. His successes inspired supporters to chant another of his slogans, "Keep Hope Alive." He told the AP: "I was able to run for the presidency twice and redefine what was possible; it raised the lid for women and other people of color. Part of my job was to sow seeds of the possibilities." U.S. Rep. John Lewis noted in a 1988 C-SPAN interview that Mr. Jackson’s two runs "opened some doors that some minority person will be able to walk through and become president."

Mr. Jackson also championed cultural change, joining calls in the late 1980s to identify Black people in the United States as African Americans. "To be called African Americans has cultural integrity — it puts us in our proper historical context," he said at the time. "Every ethnic group in this country has a reference to some base, some historical cultural base. African Americans have hit that level of cultural maturity." However, Mr. Jackson’s words occasionally caused controversy. In 1984, he apologised for privately referring to New York City as "Hymietown," a derogatory term for its Jewish population. In 2008, he made headlines for complaining that Obama was "talking down to Black people," comments caught by an open microphone. Yet, when Mr. Jackson joined the jubilant crowd in Chicago’s Grant Park to greet Obama on election night, tears streamed down his face. "I wish for a moment that Dr. King or (slain civil rights leader) Medgar Evers... could’ve just been there for 30 seconds to see the fruits of their labor," he later told the AP. "I became overwhelmed. It was the joy and the journey."

His influence extended internationally, where he met world leaders and secured diplomatic victories, including the release of Navy Lt. Robert Goodman from Syria in 1984, and the 1990 release of over 700 foreign women and children held after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. In 1999, he secured the freedom of three Americans imprisoned by Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic. In 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded Mr. Jackson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honour. "Citizens have the right to do something or do nothing," Mr. Jackson said before heading to Syria. "We choose to do something."

In 2021, Mr. Jackson joined the parents of Ahmaud Arbery in the Georgia courtroom where three white men were convicted of killing the young Black jogger. In 2022, he hand-delivered a letter to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago, calling for federal charges against former Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke in the 2014 killing of Black teenager Laquan McDonald. Mr. Jackson, who stepped down as president of Rainbow/PUSH in July 2023, disclosed in 2017 that he had sought treatment for Parkinson’s disease, but continued public appearances even as the condition made it harder for him to be understood. Earlier this year, doctors confirmed a diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy, a life-threatening neurological disorder. He was admitted to hospital in November. During the coronavirus pandemic, he and his wife survived hospitalisation with COVID-19, and he advocated for vaccination, particularly among Black communities due to higher risks. "It’s America’s unfinished business — we’re free, but not equal," Mr. Jackson told the AP. "There’s a reality check that has been brought by the coronavirus, that exposes the weakness and the opportunity."

Top 100

The Conversation (0)