Harriet Brewis

Sep 25, 2023

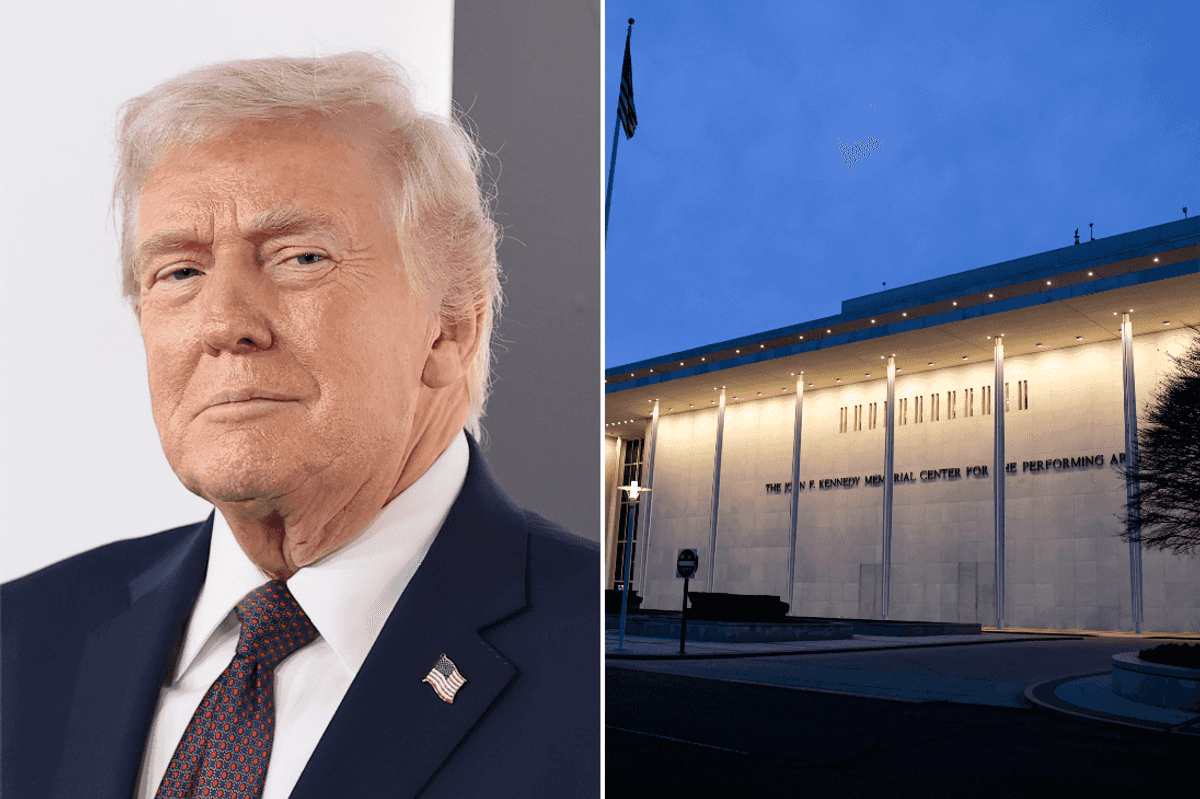

John Lithgow (left) in Peter Hyams's 1985 masterpiece '2010: The Year We Make Contact'; Jupiter's moon Europa (right)

20th Century Fox/iStock

“All these worlds are yours. Except Europa. Attempt no landing there.”

These immortal words, penned by Arthur C. Clarke and brought to life in the iconic film ‘2010: The Year We Make Contact’ ring more and more ominous the more we learn about Jupiter’s icy moon.

This is because the suggestion, made in Clarke’s sci-fi classic, that life could exist on the mysterious celestial body, seems increasingly likely thanks to new research.

The findings, published last Thursday (21 September), confirm that Europa is one of just a handful of worlds in our entire Solar System that could harbour life.

"All these worlds are yours" (A fair use clip of my favorite scene from the film 2010)www.youtube.com

Previous studies have shown that a salty ocean of liquid water lies beneath the moon’s frozen crust. However, planetary scientists hadn’t determined whether or not this sea contained the chemicals needed for life – most crucially carbon.

Now, using data gathered by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) experts have identified carbon dioxide in a specific region of Europa’s surface.

Their analysis suggests that this carbon likely originated in the hidden ocean and was not delivered by meteorites or other external sources, a news release published by the European Space Agency (ESA) reveals.

In addition, they found that the carbon was deposited on a “geologically recent timescale”.

The discovery has important implications for the potential habitability of Europa, the space agency emphasised.

“Understanding the chemistry of Europa’s ocean will help us determine whether it’s hostile to life as we know it, or whether it might be a good place for life,” Geronimo Villanueva, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, explained.

“We now think that we have observational evidence that the carbon we see on Europa’s surface came from the ocean. That’s not a trivial thing. Carbon is a biologically essential element,” added Samantha Trumbo of Cornell University – lead author of one of two papers which analysed the JWST data.

The telescope revealed that CO2 was most abundant in a region of Europa called Tara Regio — an area of what is known as “chaos terrain”.

It has earned the moniker for largely consisting of a mixture of material from the icy surface and ocean beneath.

“Previous observations from the Hubble Space Telescope show evidence for ocean-derived salt in Tara Regio,” Trumbo explained.

“Now we’re seeing that carbon dioxide is heavily concentrated there as well. We think this implies that the carbon probably has its ultimate origin in the internal ocean.”

Meanwhile, Villanueva, who authored the other paper on the findings noted: “Scientists are debating to what extent Europa’s ocean connects to its surface. I think that question has been a big driver of Europa exploration.

“This suggests that we may be able to learn some basic things about the ocean’s composition even before we drill through the ice to get the full picture.”

Villanueva’s team also searched for evidence of a plume of water vapour erupting from Europa’s surface after researchers using the Hubble Space Telescope reported tentative detections of plumes in 2013, 2016, and 2017.

However, definitive proof remains evasive – with the new Webb data showing no evidence of plume activity.

Still, Heidi Hammel, a leading scientist for the Webb programme, stressed: “There is always a possibility that these plumes are variable and that you can only see them at certain times.

“All we can say with 100% confidence is that we did not detect a plume at Europa when we made these observations with Webb.”

These findings may help inform NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which is due to be launched in October 2024.

The Clipper spacecraft will perform dozens of close flybys of the moon to further investigate whether its conditions could be suitable for life.

Just as long as it doesn’t land there…

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)