Science & Tech

Harriet Brewis

Oct 03, 2023

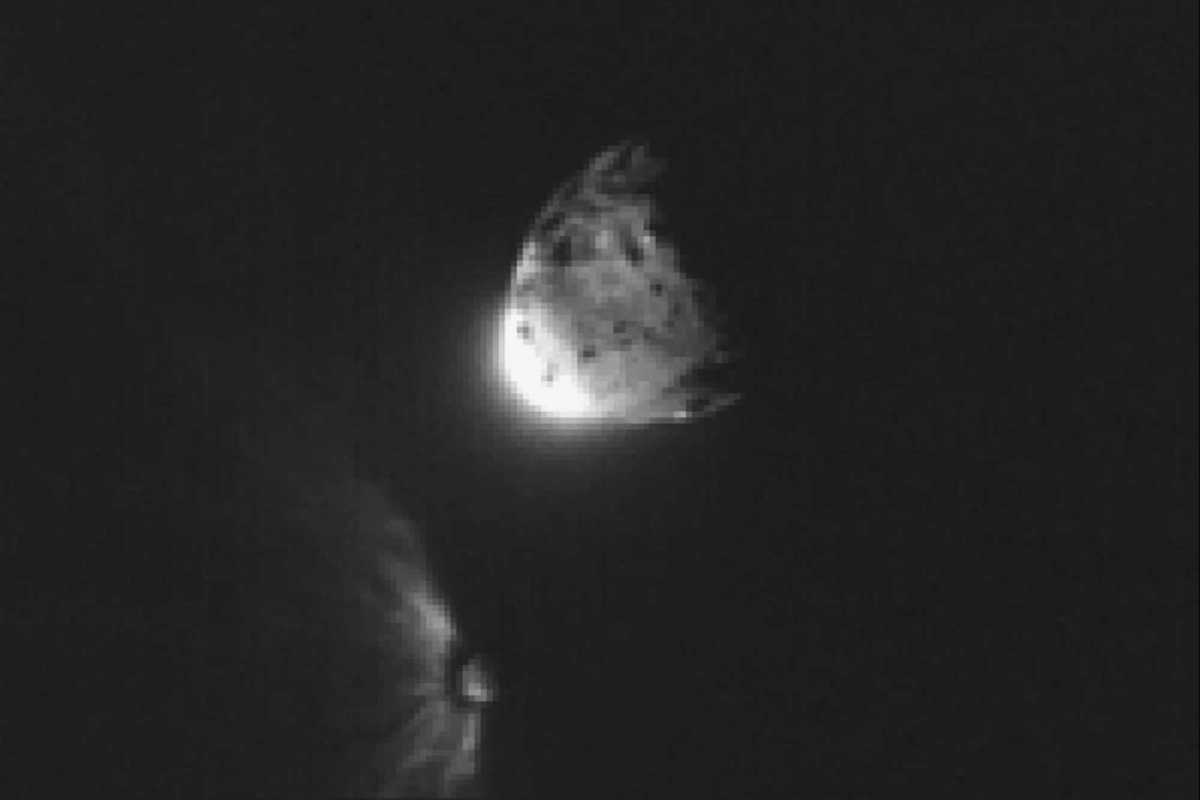

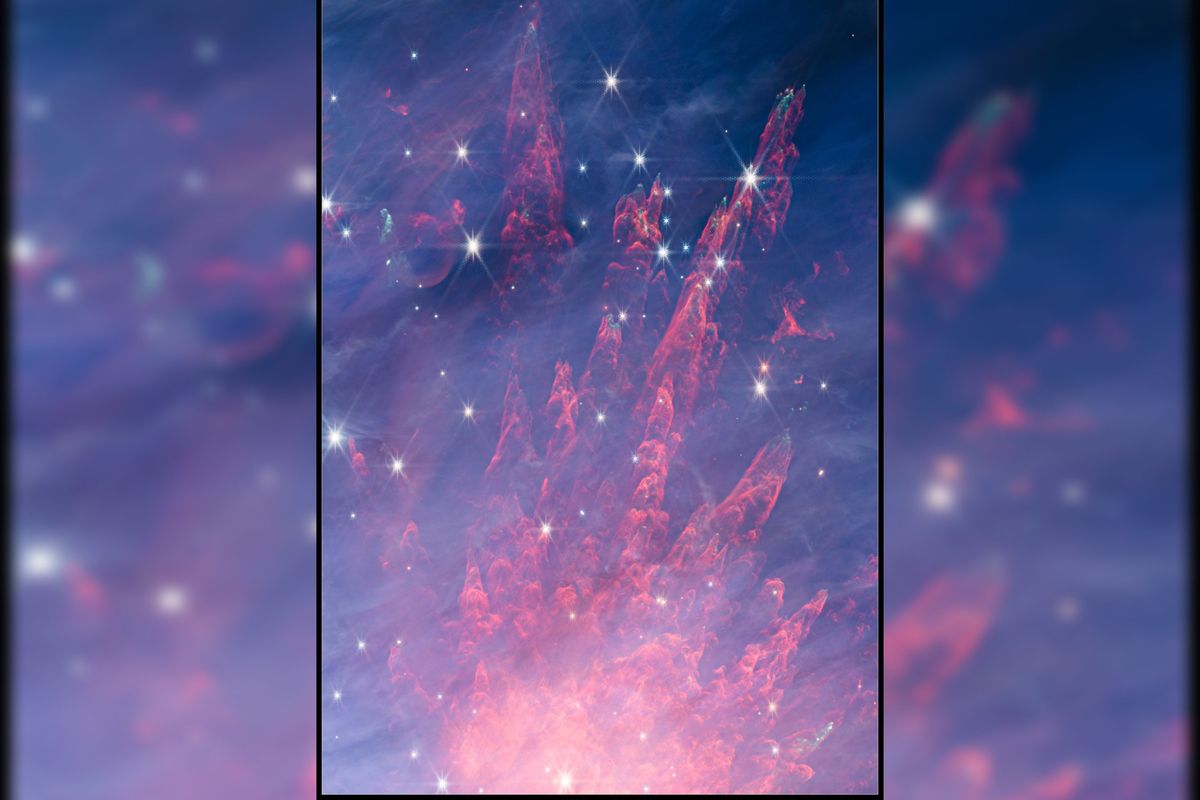

The inner Orion Nebula and Trapezium Cluster as captured by the James Webb Space Telescope

NASA, ESA, CSA

The complexities of the universe might be unfathomable to most of us, but at least we more or less know what planets and stars are.

However, we might now have to coin a name for an entirely new astronomical category after dozens of free-floating objects were discovered in our very own galaxy.

The large, mysterious entities, which have been named Jupiter-mass binary objects (or Jumbos for short) were captured by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in a stunning series of images published by the European Space Agency (ESA) on Monday (October 2).

What’s interesting about the objects is that they’re too small to be stars but they also defy our conventional understanding of a planet because they’re not orbiting a parent star.

They also appear to be moving in pairs (hence the “binary” in the name), and the JWST observed hundreds of them while surveying the iconic Orion Nebula.

Scientists are struggling to explain the Jumbos’ existence, but one theory is that they grew out of regions in the nebula where the clouds of dust and gas weren’t dense enough to make a proper star.

Another hypothesis is that they formed around stars but were then ejected into interstellar space.

"The ejection hypothesis is the favoured one at the moment," Prof Mark McCaughrean, a senior science adviser at the ESA told BBC News.

However, he continued: "Gas physics suggests you shouldn't be able to make objects with the mass of Jupiter on their own, and we know single planets can get kicked out from star systems. But how do you kick out pairs of these things together?

“Right now, we don't have an answer. It's one for the theoreticians.”

Meanwhile, Dr Heidi Hammel, an interdisciplinary scientist on the JWST programme, was less restrained in her response.

"My reactions ranged from: 'Whaaat?!?' to 'Are you sure?" to 'That's just so weird!' to 'How could binaries be ejected together?'" Dr Hammel told the BBC.

She pointed out that, so far, no evidence exists of any planetary system formation ejecting pairs of planets.

"But... maybe all star formation regions host these double-Jupiters (and maybe even double-Neptunes and double Earths!), and we just haven't had a telescope powerful enough to see them before," she suggested.

For anyone unfamiliar with the Orion Nebula, the ESA has summed it up in a handy explainer on its website.

It notes that the young star-forming region is a mere one million years old and contains thousands of new stars spanning a range of masses from 40 down to less than 0.1 times that of the Sun.

It also contains numerous brown dwarfs – objects whose mass is below seven per cent that of the Sun and which are too small to start nuclear fusion in their cores.

Then, below that, starting at roughly 13 times the mass of Jupiter, lie our new friends: the Jumbos.

These enigmatic objects appear to be planet-like in their composition, with analysis revealing that their atmospheres contain steam and methane.

However, technically they’re still not planets.

“Most of us don’t have time to get wrapped up in this debate about what is a planet and what isn’t a planet,” Prof McCaughrean told the Guardian.

“It’s like my cat is a chihuahua-mass pet. But it’s not a chihuahua, it’s a cat.”

The hot, gassy objects currently have surface temperatures of roughly 1,000°C. However, without the warm rays of a host star to heat them, they will cool rapidly – briefly presenting temperatures in a habitable range before getting really, really cold.

Furthermore, as gas giants, it’s highly unlikely that water could form on their surface at any point, so don’t expect to see them hosting alien life any time soon… or ever.

Prof Matthew Bate, the University of Exeter’s head of astrophysics, admitted that the JWST's Jumbo finding could force experts to rethink their understanding of how objects form in the universe.

Prof Bate, who wasn’t involved in the research, told the Guardian: “I don’t know how to explain the large numbers of objects they’ve seen.

“It seems we’re missing something in all of the theories we’ve got so far. It seems that there’s a mechanism that’s forming these [objects] that we haven’t thought of yet.”

“It’s pretty rare that this kind of discovery is made,” he added.

“In the last decade, a lot of us thought we understood star formation pretty well. So this is really a very, very surprising result and we’re going to learn a lot from it.”

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)