News

Jake Hall

Jul 18, 2018

Artwork: Courtesy of Conor Collins / Photo: Princess Diana Archive

Despite a series of landmark medical advances which have vastly improved and extended the lives of HIV-positive people in the UK, the virus is still too often linked to shame and stigma.

The fact is that there’s nothing to be ashamed of. Studies have shown that patients on ART (anti-retroviral treatment) can effectively suppress their viral load to ‘undetectable’ levels; in a nutshell, any patient on this controlled medication can have unprotected sex freely with no fear of transmission.

A three-year NHS trial of PrEP, a preventative pill, has also been commissioned, meaning that vital drugs are now more easily accessible than ever before. There’s even PEP, a pill which can be taken by someone who thinks they may have been at risk of transmission of the viral.

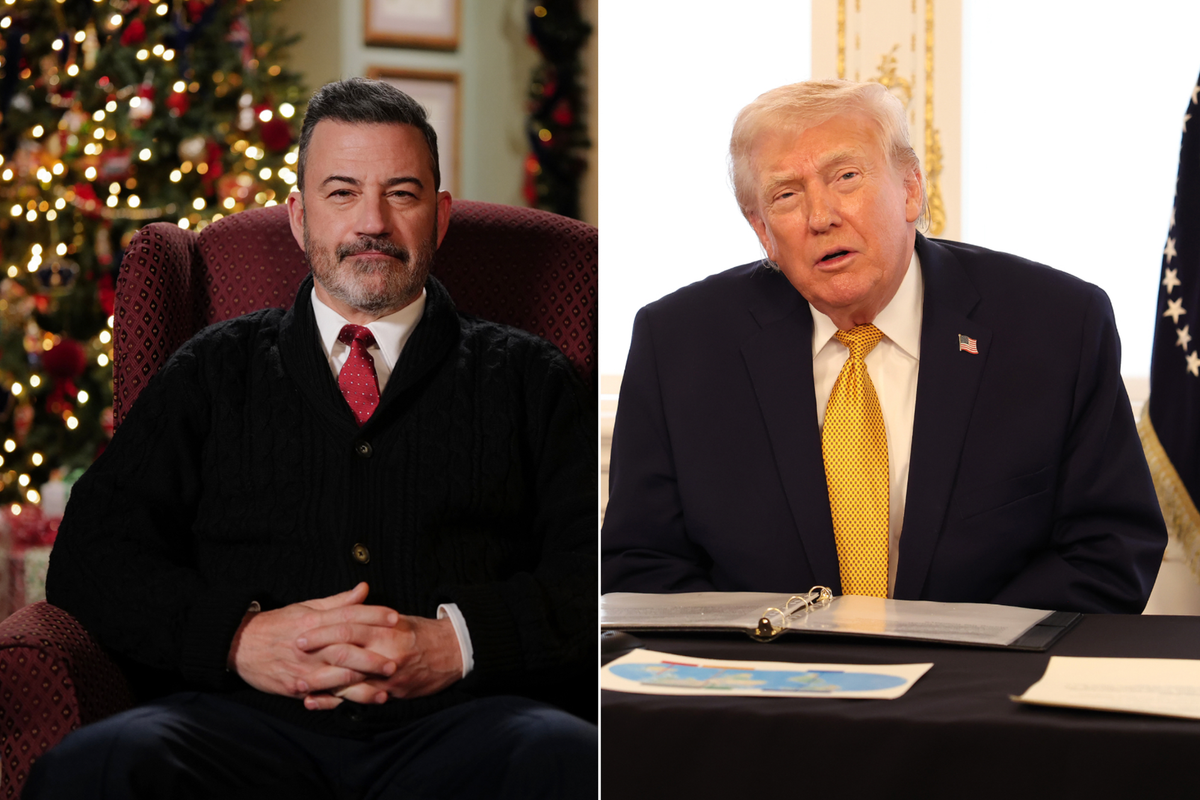

Despite these facts, public conversations around HIV are all too often rooted in myth or stigma. Artist Conor Collins has sought to remedy this rhetoric with a unique portrait of Princess Diana, created with a mixture of diamond dust and HIV+ positive blood.

Since sharing the artwork online yesterday, Collins says he’s been met with praise online.

“The reaction has been really great,” he told indy100.

People have been getting behind the message and sharing it loads.

I want to get the message out there as much as I can – the stigma and shame must come to an end.

His choice of Princess Diana was symbolic; in 1987, as media speculation and fear-mongering around the AIDs epidemic, then often nicknamed the ‘gay plague’, was at an all-time high. Despite the stigma and misinformation being spread by incendiary newspaper headlines, Diana proudly shook the hand of a man whose life was being slowly whittled away by the virus.

Collins’ artwork makes reference to this necessary breakthrough in public perception of HIV-positive patients, but also highlights that some myths have refused to disappear.

“I think the most common myth that’s still prevalent today is that HIV is a death sentence,” he explains. “When the epidemic rose and the world started paying attention in the 1980s, so little was understood about the virus, how it was transmitted and how to treat it. The lack of knowledge, funding and the stigma surrounding HIV led to untold numbers of deaths.”

There has been a horrendous amount of loss, and that should never, ever be forgotten.

However, those diagnosed and treated early today live healthy, happy lives that are just as long as those of people without HIV.

He also cites 2016 statistics which show that 93% of patients diagnosed with HIV are now undetectable, and therefore don’t pose any kind of transmission risk to sexual partners. “It’s also widely accepted within the medical community that percentages of undetectable patients will rise yet again when reported soon.”

The overwhelming number of HIV-positive people today cannot transmit HIV.

Collins speaks eloquently on discrimination, but he says his art is never intentionally political; instead, it’s a medium for him to express his feelings about the world more generally. “Those close to me will know I often struggle trying to communicate what I want to say, or what I feel about the world around me.”

I am pretty dyslexic and dyspraxic, so often when I try to explain what I think or feel in words it can get muddled, like a mess of alphabetti spaghetti.

With my art, I’m able to distil my message and convey exactly what I want to say. Then it’s anyone’s free choice to decide whether or not they want to listen.

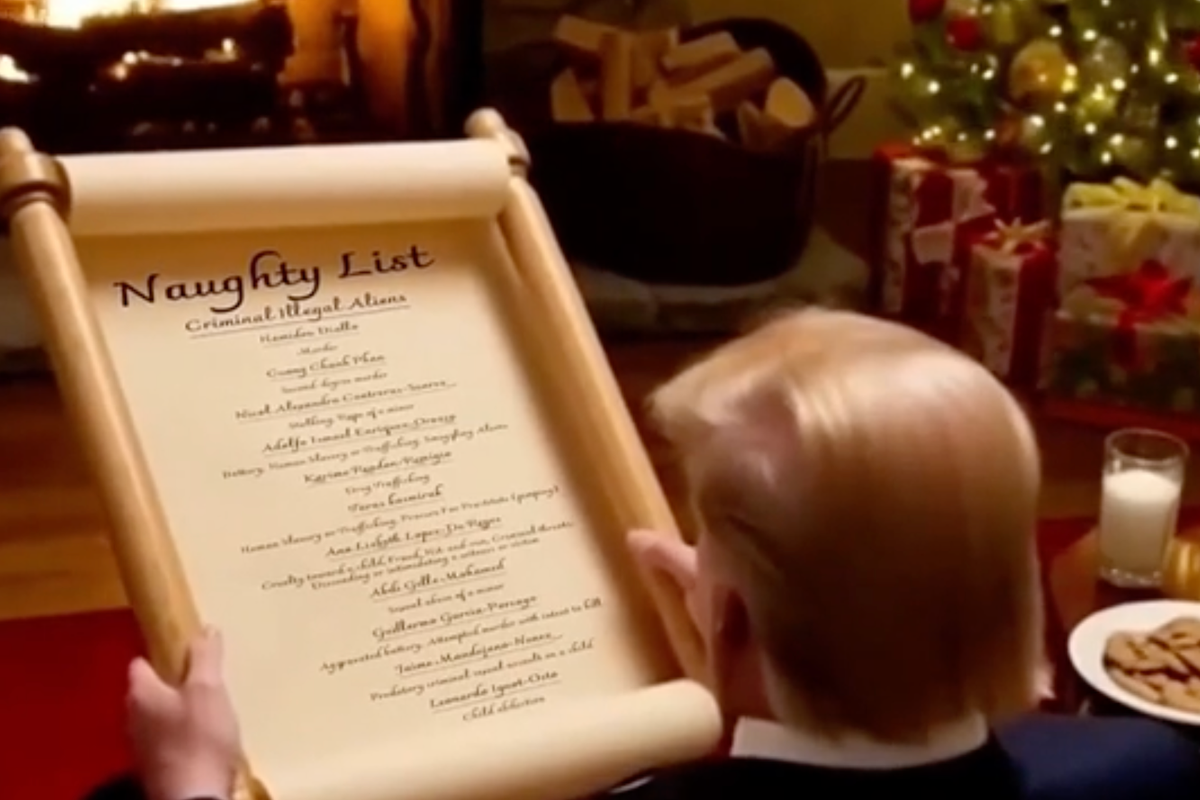

Collins frequently shares his work via social media, either through his Twitter or his Instagram. He tends to use experimental materials – like the HIV-positive blood used for this Diana portrait – to hint at deeper meaning, such as the whitewashed dollars he used to create a viral image of Donald Trump last year.

Embedded within this makeshift fabric was a rich tapestry of tiny, bigoted statements, all of which were combined to form the details of the artwork.

This piece may also be political, but there's one overarching thread which connects all of his artwork: acceptance.

“We all deserve to be loved and treated with dignity", he states before reminding us that trying to make someone else feel ashamed is a choice – and one which won’t achieve anything.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)