News

Tony Whitfield

Mar 23, 2018

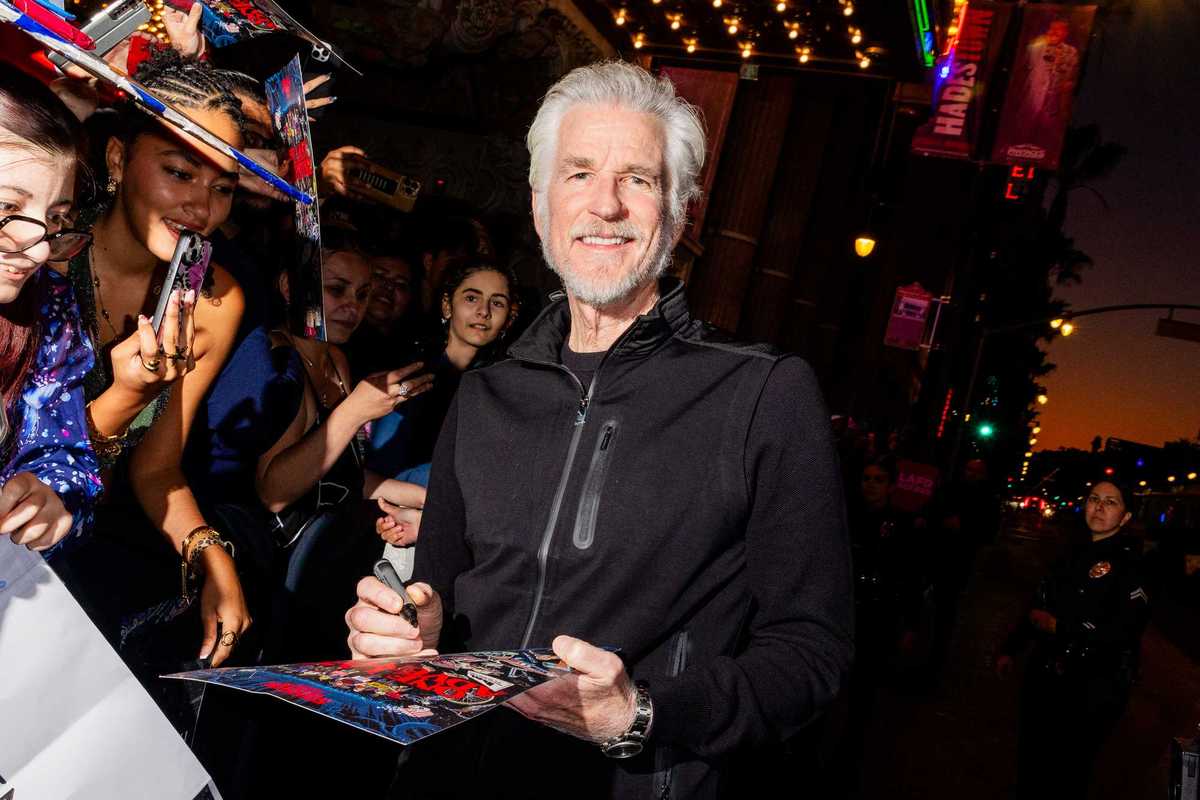

Dinosaurs were wiped out by an asteroid strike 66 million years ago

iStock

Humans are sleepwalking into a mass extinction of species not seen since the demise of the dinosaurs, British scientists warned.

Man-made global change is threatening the diversity of different creatures that have taken millennia to evolve to live in niche habitats.

Creatures that have moved into delicate ecosystems such as coral reefs often live in symbiosis with others and are the slowest to recover their diversity if damaged.

But global warming and rising sea levels threatened to wipe out many species that cannot adapt to change quickly enough "in a blink of an eye."

In particular freshwater habitats are teeming with diverse birds and mammals but they are often form isolated pockets which are vulnerable to sudden change.

Professor of Evolutionary Paleobiology Matthew Wills at the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath said:

We are sleepwalking into a mass extinction of a magnitude unparalleled since the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Astonishingly, we know remarkably little about the physical and biological forces that shape patterns of diversity on a global scale.

For example, why are there over a million species of insects but only 32 species in their immediate sister group, the little known remipedes?

Diversity takes millions of years to evolve, but can be damaged in the blink of an eye.

We are already losing diversity that has never even been documented, so it's vitally important to understand the mechanisms that drive evolution into new species.

The scientists looked at how the humble caridean shrimp has evolved and diversified since it first appeared in the Lower Jurassic.

There are now around 3,500 species worldwide living in salt and fresh water habitats and are a vital component of the marine food chain, and an important contribution to fisheries worldwide.

Research Fellow Dr Katie Davis, an evolutionary palaeobiologist at the University of York explained:

Understanding the processes that shaped the strikingly irregular distribution of species richness across the Tree of Life is a major research agenda.

Changes in ecology may go some way to explain the often strongly asymmetrical fates of sister clades, and we test this in the caridean shrimps.

There are, depending upon estimates, between two and 50 million extant species of animals (Metazoa), all derived from a single common ancestral species that lived some 650 million years ago.

Net rates of speciation therefore exceed rates of extinction, but the balance of these processes varies greatly, both between clades and throughout geological time.

The scientists examined the patterns of diversity change across the crustaceans's evolutionary tree.

By time-calibrating the largest ever evolutionary tree for carideans against both fossil and molecular dates, it was possible to explore where rates of diversification sped up and slowed down over the last 200 million years.

They found the shrimp have independently transitioned from marine to freshwater habitats repeatedly, creating much richer pockets of biodiversity.

The relative isolation of lakes and rivers appear to increase the diversity of species in a similar way to Darwin's finches on island chains.

But rising sea levels caused by climate change could put these pockets at risk, disrupting these freshwater distributions and leading to extinctions as a result.

By contrast, many marine shrimp live in close symbiotic associations with a variety of other animals including corals and sponges, which appears to have slowed their diversification rate.

Symbioses are most common in shallow reef settings: among the most diverse but notoriously delicately balanced and threatened marine ecosystems.

The researchers said lower rates of diversification mean it will take longer for carideans to recover from the extinctions that are already inevitably underway.

Co-author Sammy de Grave, head of research at the Oxford University Museum added:

Our study has shown how shrimp have diversified and adapted according to their specific habitats, giving insight into why some groups are so much more species rich than others.

The study was published in the journal Communications Biology.

SWNS

Top 100

The Conversation (0)