Britain is not institutionally racist, indeed, it should be seen as a “model” on race to other countries, a landmark Government review has concluded.

The report by Number 10’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities found that the UK had become a more open society and children from ethnic minorities outperform their white peers at school.

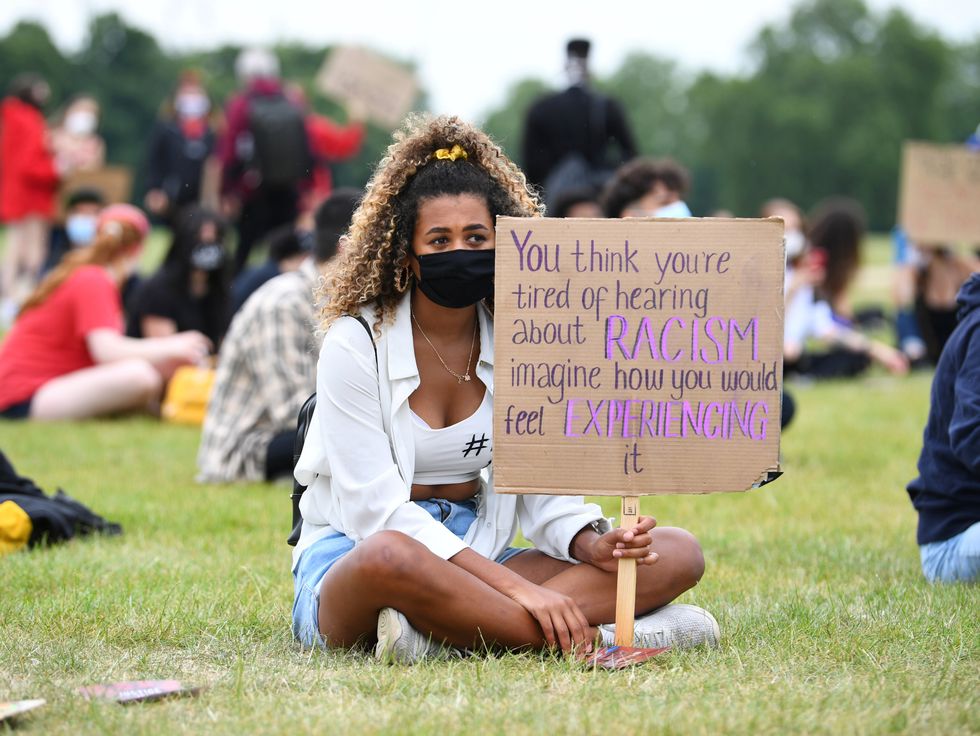

The commission – formed last summer in response to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement – notes that while racism does still persist across the UK, achievements in areas including education and employment make the country “a model for other white-majority countries”.

The findings, which were published in full at 11.30am on Wednesday, have already been condemned by some equality experts as a “grotesque insult”.

So how are people responding to the report? What are its key points? And what evidence is there to suggest that the UK isn’t such a “model” country when it comes to race?

Read more:

- Chinese takeaway goes viral for savage responses to customers

- Man’s marriage proposal brutally rejected in front of a busy shopping mall

- Trump uses new website to rewrite presidential history – here are all the things he forgot to include

- 35 of the funniest memes about the Ever Given

- Wendy’s chicken sandwich nightmare sparks fierce TikTok debate

Here’s how people reacted after a summary of the report was released on Tuesday night

Labour MP David Lammy, branded the report an “insult to anybody and everybody across this country who experiences institutional racism”.

Speaking on LBC this morning, he said: “British people, white and black, are dying to turn the page on racism.

“They are working in food banks to support the marginalised. They are teaching in after-school clubs to raise awareness. They are working in rehabilitation centres to end the cycle of disproportionate mass incarceration.

“Boris Johnson has just slammed the door in their faces by telling them that they’re idealists, they are wasting their time. He has let an entire generation of young white and black British people down.”

He continued: “Let’s not forget that this report was rushed out in response to the overwhelming desire for change after the murder of George Floyd where thousands of people rallied for the black men, women and children suffering still, excluded in this country because of institutional racism.

“This report could have been a turning point and a moment to come together. Instead, it has chosen to divide us once more and keep us debating the existence of racism rather than doing anything about it.”

Other critics hit out at the Government’s decision to only release “cherry-picked” lines from the report overnight before publishing the full 264-page document hours after the morning’s media round.

Nadine White, the UK’s only Race Correspondent, pointed out: “Despite my numerous requests for updates over the weeks (months) about when the report will be published, the govt did not send details of the Race Commission’s report to me - the only Race Correspondent in the UK.

“But other journalists received it.”

What have we learned since the full report was published?

ITV News’s UK editor Paul Brand has shared some key excerpts.

He wrote a few minutes after the report’s release: “Controversially for some, report suggests individuals determine their own success.

“It calls for analysis of "the extent individuals and their communities could help themselves through their own agency, rather than wait for invisible external forces to assemble to do the job."

“More controversially, it seeks a reappraisal of slavery,” he added.

Citing the report, he continued: “’There is a new story about the Caribbean experience which speaks to the slave period not only being about profit and suffering but how culturally African people transformed themselves into a re-modelled African/Britain.’”

This point was also highlighted by the Mirror’s online political editor Dan Bloom.

Here’s some more reaction from the Twittersphere:

On the other side of the debate, Laurence Fox – who hit the headlines last year for his BBC Question Time argument over race – tweeted: “This is a bad day for all the race hustlers(…) And a good day for the millions of warm welcoming and tolerant people of this wonderful country.

“Reclaim the truth.”

Former MEP Martin Daubney commented: “This will upset the grievance mongers.”

And the head of the Equality and Human Rights commission, Baronness Kishwer Falkner, said that the report “rightly identifies the varied causes of disparities and (...) giv es the government the opportunity to design policy targeting the sources of inequality”.

However, she added: “While Britain has made great progress towards race equality in the last 50 years, there’s still much more to do.”

Meanwhile, the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities chairman, Tony Sewell, insisted: “No one in the report is saying racism doesn’t exist.

But, he added, in an interview with BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme: “the evidence of actual institutional racism, that wasn’t there, we didn’t find that in our report”.

Also appearing on the morning’s media round, shadow foreign secretary Lisa Nandy told Sky News she had not yet read the full report but it was clear that action was needed.

She said: “It’s right to recognise that progress has been made and it’s right to celebrate it, but that shouldn’t in any sense mean we don’t see the very real problems in front of us and start to act on them.

“The Government has report after report after report … what we really need now is some action to implement them.”

The Labour MP added that statistics on disproportionate rates of school exclusion and arrest among black children underlined evidence of “an institutional problem”.

She said: “What would be a real shame and roll back progress is if today we ended up in a situation where the Government is seeking to downplay or deny the extent of the problem, rather than doing what it should be doing, which is getting on the front foot and tackling it.”

What are the report’s key points?

The Commission said claims that Britain is still institutionally racist are not borne out by the evidence, but overt racism remains.

In a foreword, Sewell said evidence had found that factors such as geography and socio-economic background had “more significant impact” on life chances than the existence of racism.

“Put simply, we no longer see a Britain where the system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities,” the Commission’s chairman said.

“The impediments and disparities do exist, they are varied, and ironically very few of them are directly to do with racism.”

He continued: “Too often ‘racism’ is the catch-all explanation and can be simply implicitly accepted rather than explicitly examined.

“The evidence shows that geography, family influence, socio-economic background, culture and religion have more significant impact on life chances than the existence of racism.

“That said, we take the reality of racism seriously and we do not deny that it is a real force in the UK.”

The report states that there have been improvements such as increasing diversity in elite professions and a shrinking ethnicity pay gap, although disparities remain.

It also found that children from many ethnic communities do as well or better than white pupils in compulsory education, with black Caribbean pupils the only group to perform less well.

And it says the pay gap between all ethnic minorities and the white majority population has shrunk to 2.3 per cent, and is not significant for employees under 30.

The document hails education as “the single most emphatic success story of the British ethnic minority experience” and the most important tool to reduce racial disparities.

Success in education and, to a lesser extent, the economy “should be regarded as a model for other white-majority countries”, the Commission adds.

The report states: “We found that most of the disparities we examined, which some attribute to racial discrimination, often do not have their origins in racism.”

However, it also notes that some communities continue to be “haunted” by historic racism, which is creating “deep mistrust” and could be a barrier to success.

It makes 24 recommendations, including for extended school days to be phased in, starting with disadvantaged areas, to help pupils catch up on missed learning during the pandemic.

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds should also have access to better quality careers advice in schools, funded by university outreach programmes.

And it is calling for more research to examine the drivers in communities where pupils perform well, so these can be replicated to help all children succeed.

The Commission also recommends that the acronym BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) should no longer be used as differences between groups are as important as what they have in common.

And it calls for organisations to stop funding unconscious bias training and for the Government and experts to develop resources to help advance workplace equality.

The report also thanks the “mainly young people” behind the BLM movement for putting the focus on race but said progress could not be achieved by “cleaving to a fatalistic account that insists nothing has changed”.

“We were established as a response to the upsurge of concern about race issues instigated by the BLM movement,” the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities report’s conclusion said.

“We owe the mainly young people behind that movement a debt of gratitude for focusing our attention once again on these issues.

“But most of us come from an older generation whose views were formed by growing up in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Our experience has taught us that you do not pass on the baton of progress by cleaving to a fatalistic account that insists nothing has changed.”

What points have critics of the report raised?

People have pointed to significant disparities in areas such as healthcare and criminal justice.

For example, Black men are 26 per cent more likely than white men to be remanded in custody, according to analysis by the Prison Reform Trust. They are also nearly 60 per cent more likely to plead not guilty.

In addition, Black people are nine times more likely to be stopped and searched by police than white people, according to statistics released by the Home Office in October last year.

Searches of all Black and minority ethnic groups were four times higher than those of white people, the Government department confirmed.

People from ethnic minorities are also more likely to test positive for Covid-19 compared with white groups.

A report released by the Joint Biosecurity Centre (JBC) in February found that “existing socioeconomic inequality” had left Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities more exposed to coronavirus due to living in cramped, multigenerational housing in deprived areas and working in public-facing jobs.

Similar conclusions were drawn in a report published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in January, although it added that “cultural and structural racism also adversely affect health”.

Black Britons are also significantly more likely to die of the disease than their white counterparts.

Mortality rates for deaths involving coronavirus are highest among Black men, at 255.7 deaths per 100,000 population. This falls to 119.8 for Black women.

Both figures are markedly higher than those reported among white men, who were found to have the lowest Covid mortality rate at 87.0 deaths per 100,000.

Meanwhile, more Black and minority ethnic staff in the NHS in England have reported experiencing discrimination and are less likely to feel their organisation provides equal opportunities compared with white employees.

An NHS staff survey, published earlier this month, found that that Black and minority ethnic staff were more likely to report working in coronavirus settings than white staff.

The survey found that 47 per cent of BAME staff said they had worked on a Covid-19 specific ward or area at any time compared with 31 per cent of white staff.

Almost a quarter (23 per cent) of BAME staff said they had been redeployed due to the pandemic at any time compared with 17 per cent of white staff.

The findings also showed half of all staff who worked in these settings had felt unwell due to work-related stress, as well as a drop in the proportion of overall staff satisfied with their pay.

The survey of more than 500,000 employees in England found that 16.7 per cent of Black, Asian and minority ethnic staff reported experiencing discrimination at work from a manager, team leader or other colleague in the previous 12 months, up from 14.5 per cent in 2019.

This compared with 6.2 per cent of white staff – up from six per cent in 2019.

Danny Mortimer, chief executive of the NHS Confederation, said the data on the “continued poorer experience of ethnic minority staff starkly reminds NHS leaders that staff experience varies unacceptably in their organisations”.

All of this suggests that there is still a long way to go before Britain can comfortably call itself a “model” to other countries.

More: To the people who don’t believe racism is a public health threat