Breanna Robinson

Aug 14, 2021

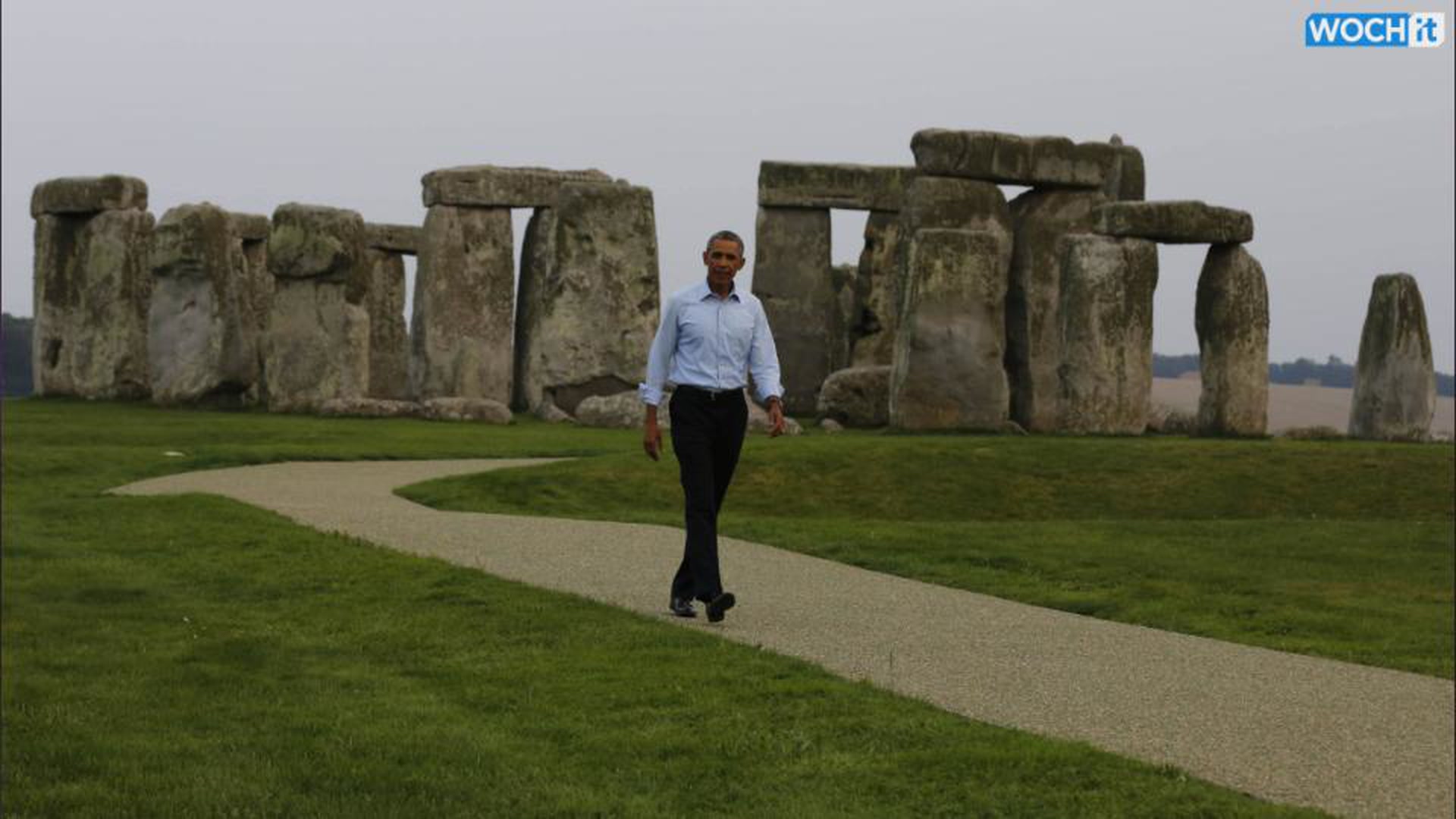

A newly analysed piece of Wiltshire, England’s Stonehenge puts the age of the prehistoric monument’s rocks at 2 billion years old.

As a result, this revealed new insights into the monument’s impressive longevity, according to a recent study in the journal PLOS ONE.

A series of investigations that allowed researchers to peer inside one of Stonehenge's 52 sandstone megaliths, known as sarsens, to learn more about its geology and chemistry.

They looked at Stone 58, a core sample taken from one of the sarsens during conservation efforts in the 1950s. It was stored in the US for decades before being returned to the UK in 2018 for research, according to Reuters.

The sarsens are made of silcrete, a type of stone created by groundwater washing over buried silt within a few yards (meters) of the ground surface.

The study revealed the interior structure of Stone 58. It revealed that the silcrete is mostly made up of sand-sized quartz grains held together by an interlocking mosaic of quartz crystals. Even when subjected to millennia of wind and weather, quartz is incredibly resilient and does not easily shatter or disintegrate.

“This explains the stone’s resistance to weathering and why it made an ideal material for monument-building,” said David Nash, a geomorphologist at the University of Brighton.

The sarsens were built circa 2500 BC on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire by late Neolithic people. Each is around 23 feet tall above ground, with another 7 feet underneath, and weighs about 24 tons.

The core sample, which is about an inch in diameter and a yard long, is brighter than the megaliths' pale gray shell.

It was given to Robert Phillips, who worked for a conservation company, as a token of appreciation. When he relocated to the United States in 1977, he took it with him with permission. He opted to return it to the UK for research in 2018. In the year 2020, he passed away.

Nash told Reuters that getting access to the core was the “Holy Grail” of the research and said, “All the previous work on sarsens at Stonehenge involved samples either excavated from the site or knocked off from random stones.”

The researchers studied shards and wafer-thin slices of the core sample using CT scanning, X-rays, microscopic analysis, and numerous geochemical techniques, as such testing was prohibited for megaliths at the site.

It’s still not entirely clear exactly when the rock was formed, but researchers discovered that some of the sand grains wedged in the rock were most likely present in the Mesoproterozoic era which was around 1 to 1.6 billion years ago.

Check out the full PLUS ONE study about the Stonehenge rocks here.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)