Andy Gregory

Feb 08, 2021

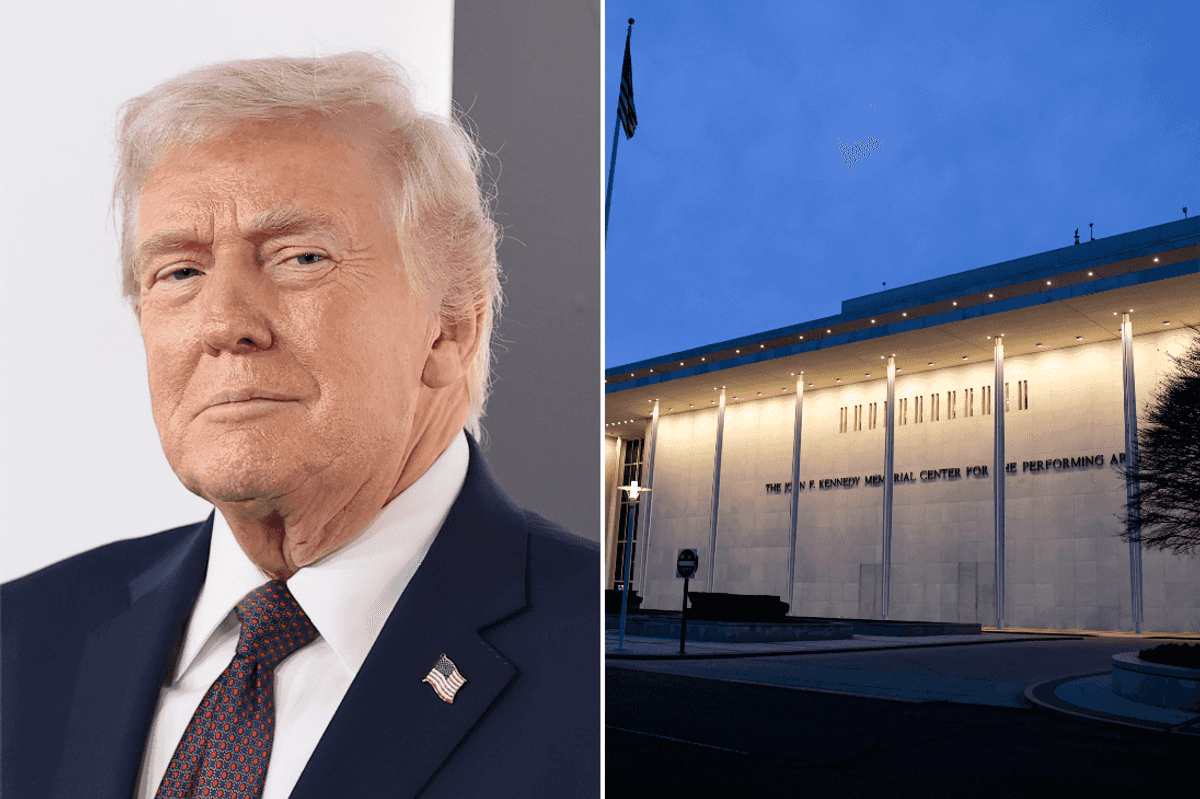

The US Senate is to debate the impeachment of Donald Trump this week for a second time, deciding whether to prosecute the former president on charges of "incitement of insurrection" after his supporters fatally stormed the Capitol building.

In a trial beginning on Tuesday, senators will hear evidence – some new and some all-too-familiar – of how and why the now-infamous events on 6 January unfolded before deciding whether to convict Trump.

House of Representatives prosecutors have argued that the 45th president – with his baseless accusations of voter fraud – is "singularly responsible" for the violent insurrection, by “creating a powder keg, striking a match, and then seeking personal advantage from the ensuing havoc”.

But Trump's lawyers appear set to strenuously deny all accusations against him, with iterations of the word "denies" littering the 14-page rebuttal published last week, which outlines how the former president will argue the accusations against him.

So how can we expect Trump's lawyers to fight his case?

His defence appears likely to centre on two main arguments.

1. That the impeachment trial is illegitimate because Trump is no longer president

Trump has frequently sought to paint accusations against him as entirely false, leading to the terms "fake news", "hoax" and "witch hunt" becoming synonymous with his presidency.

This rhetoric became particularly heightened during his first impeachment trial, when the Senate voted not to convict him on charges of abuse of power and obstructing Congress over his conduct in a phone call with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky.

While the evidence appears in some ways more clear-cut than in 2020 – with Trump's supporters having started their march on the Capitol midway through an incendiary rally held by him and his allies – the former reality TV star is once again questioning the legitimacy of the entire proceedings instead.

With Trump accounting for two of the four impeachments in US history, the trial marks the first time that a president has been tried in the Senate after leaving the White House.

His lawyers will likely argue that this is "unconstitutional".

“We’re trying to win a case on a bunch of procedural objections,” one of his attorneys, Bruce Castor Jr, told Reuters last week.

“This is ‘Law School 101’ stuff. This isn’t advanced legal treatises in bound volumes that are used in the Supreme Court as references.”

It's an argument that appears to hold sway with a GOP still clearly loyal to its once-golden goose.

While the approval of two thirds of the Senate is needed to convict Trump, a fortnight ago all but five Republicans voted with senator Rand Paul on the premise that the trial is unconstitutional and should not go ahead.

But it emerged that even conservative constitutional scholar Jonathan Turley – who helped structure Paul's challenge – had concluded the Senate was “correct in its view that impeachments had extended to former officials” in a previous case involving ex-Secretary of War William Belknap in 1876.

And in an open letter published in Politico, more than 150 influential legal scholars have insisted that "history supports" trying a president even after they have left the White House.

“If an official could only be disqualified while he or she still held office, then an official who betrayed the public trust and was impeached could avoid accountability simply by resigning one minute before the Senate’s final conviction vote," they wrote.

"The Framers did not design the Constitution’s checks and balances to be so easily undermined. History supports a reading of the Constitution that allows Congress to impeach, try, convict, and disqualify former officers."

2. That Trump's words are protected by the First Amendment

House prosecutors allege that Trump “summoned a mob to Washington, exhorted them into a frenzy, and aimed them like a loaded cannon down Pennsylvania Avenue” – picking out individual phrases used by the former president at his "Save America" rally, such as "fight like hell".

But the rebuttal from Trump's lawyers argues: “Like all Americans, the 45th president is protected by the First Amendment.”

His lawyers go on to claim that the impeachment charge “violates the 45th president’s right to free speech and thought”.

But constitutional experts from across the political spectrum – many of those who also lent their voices to the letter referenced above – have denounced this claim as "legally frivolous", in a letter shared with The New York Times.

They argue that the First Amendment, intended to protect citizens' freedoms from the government, does not apply to impeachment proceedings – which seek to establish not whether Trump's conduct was criminal, but whether he betrayed his presidential oath to an extent equating to a "high crime or misdemeanour".

Furthermore, they argued that such a defence would likely fail in a normal court of law, suggesting the evidence against Trump would be strong enough for a defendant to be tried for incitement.

It also appears that Trump's lawyers could seek to counter the use of footage of the 45th president's words by using "duelling video" showing incendiary statements made by Democrats.

“I think you can count on that,” Castor told Fox News last week. “If my eyes look a little red to the viewers, it's because I've been looking at a lot of video.”

Insufficient evidence exists to show Trump's election fraud claims were false

While the above two points are widely expected to form the basis of Trump's defence, Rolling Stone highlighted another line in the rebuttal document.

Referring to Trump's claims of voter fraud, his lawyers stated: "Insufficient evidence exists upon which a reasonable jurist could conclude that the 45th President’s statements were accurate or not, and he therefore denies they were false.”

It remains unclear whether the president will maintain his baseless claims over voter fraud in the Senate trial, which have been thrown out in courts across the country.

But in some ways, his possible use of such an argument seems a fitting end to a presidency marked by its divergence from reality and its alignment with conspiracy theories – starting with the racist "birther" movement and ending with QAnon.

Rolling Stone's Andy Kroll writes that Trump's lawyers "employ the same tactic as the promoters of viral conspiracy theories do – arguing, in essence, that if you can’t fully disprove the president’s repeated claims about corrupt voting-machine companies, stolen votes, and corrupt public officials, then you can’t say they’re false".

But many expect that doing so would be a remarkable own-goal.

Addressing Trump's lawyers' claim that he was entitled to “express his belief that the election results were suspect”, former Republican National Committee chair Michael Steele told The Guardian: “If they present that as an argument, they’ll get laughed out of the out of the chamber.

"They would actually be lying. They would be presenting false evidence because they could make the allegation. And if I’m a senator, [I'd say] ‘Show me the proof. You mean to tell me you have proof that 60 courts and the supreme court didn’t have?’”

Watch this space.

More: Trump makes history as the first president to be impeached twice

Top 100

The Conversation (0)