Science & Tech

Harriet Brewis

Jun 10, 2024

When You Die, Your Brain Tells You That You’re Dead

Underknown - INSH / VideoElephant

Cotard’s syndrome is one of the strangest conditions known to modern medicine and, thankfully, it is also one of the rarest.

People suffering from the illness believe that they, or parts of their body, no longer exist, and the effects can be truly astonishing.

Some people with Cotard’s have reportedly died of starvation, believing they no longer needed to eat. While others have tried to destroy their bodies using acid, viewing this as the only way to free themselves of being the “walking dead”.

Perhaps the most famous case of the disorder was suffered by a man named Graham, who woke up one morning convinced his brain had died.

But what’s most remarkable about the story is that his brain really did appear dead on medical scans, leaving doctors bewildered.

Graham relayed his extraordinary experience to New Scientist back in 2013, explaining that he believed he had “killed” his brain in a failed suicide attempt.

He explained that he had been suffering from severe depression at the time and so had tried to take his own life by placing an electrical appliance in the bath with hum.

Eight months later, he told his doctor that his brain was dead or was, at the very least, missing.

“It’s really hard to explain,” Graham told the magazine. “I just felt like my brain didn’t exist any more. I kept on telling the doctors that [medication wasn’t] going to do me any good because I didn’t have a brain. I’d fried it in the bath.”

He admitted that he swiftly grew frustrated with medics, refusing to accept that his brain was both present and fully functioning despite his ongoing ability to talk, breathe and, ultimately, continue living.

He was eventually put in touch with the neurologists Adam Zeman and Steven Laureys, of the universities of Exeter and Liège respectively.

“It’s the first and only time my secretary has said to me: ‘It’s really important for you to come and speak to this patient because he’s telling me he’s dead,'” Laureys later recalled to New Scientist.

Meanwhile, Zeman admitted that Graham “was a really unusual patient,” but said his dogged belief in his own brain death was clearly “a metaphor for how he felt about the world.”

“His experiences no longer moved him,” the Exeter professor said. “He felt he was in a limbo state caught between life and death”.

Indeed, although Graham’s brothers took care of him, making sure he ate, drank and performed other vital tasks, he said he “didn’t feel pleasure in anything.”

“I used to idolise my car, but I didn’t go near it,” he added. “All the things I was interested in went away.”

“I lost my sense of smell and my sense of taste. There was no point in eating because I was dead. It was a waste of time speaking as I never had anything to say. I didn’t even really have any thoughts. Everything was meaningless.”

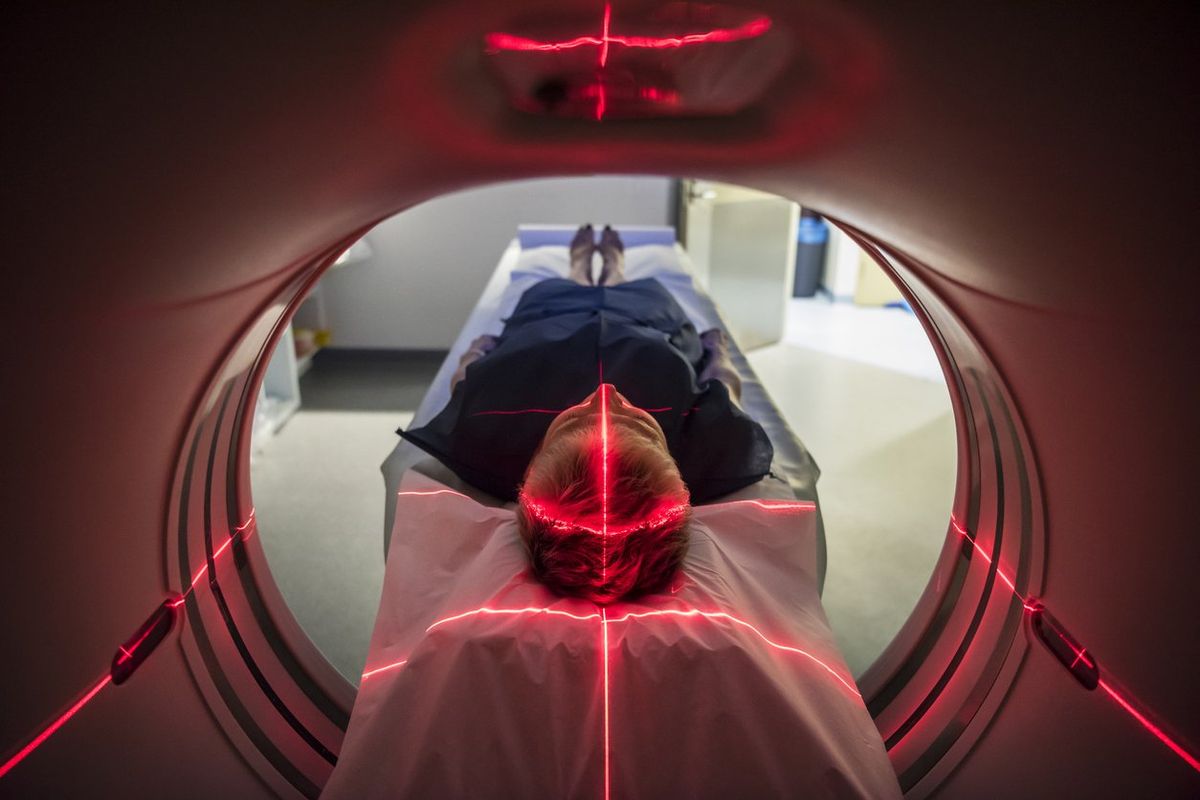

As part of their investigations into Graham’s symptoms, Zeman and Laureys conducted a PET scan to monitor metabolic activity across his brain.

It was the first scan of its kind ever to be taken of a person with Cotard’s and the results were staggering.

They revealed that metabolic activity across large areas of Graham’s frontal and parietal brain regions was so low, it resembled that of someone in a vegetative state.

Some of these areas are part of what is known as the “default mode network” – a complex system thought to be key to core consciousness and our theory of mind, New Scientist notes.

This network is behind our ability to remember the past and have a sense of self, including the understanding that we are the agent responsible for a particular action.

“I’ve been analysing PET scans for 15 years and I’ve never seen anyone who was on his feet, who was interacting with people, with such an abnormal scan result,” Laureys said.

“Graham’s brain function resemble[d] that of someone during anaesthesia or sleep. Seeing this pattern in someone who is awake is quite unique to my knowledge.”

Nevertheless, Zeman was quick to stress that we shouldn’t draw too many conclusions from a scan of a single person, noting that the results could have been affected by the antidepressants he was taking.

“It seems plausible that the reduced metabolism was giving him this altered experience of the world, and affecting his ability to reason about it,” he said.

Laureys agreed, adding: “There [are] many things we don’t know about how to define consciousness.”

But, if nothing else, strange cases such as Graham’s contribute to our grasp of how the brain develops its perception of self and how this can be disrupted.

No one knows just how rare Cotard’s syndrome may be. A study of 349 elderly psychiatric patients in Hong Kong, published in 1995, found that two were showing signs of the condition.

However, given recent advancements in the treatment of depression – from which Cotard’s most often derives – researchers suspect the syndrome is exceptionally uncommon today.

The good news is that, over time, and with the help of psychotherapy and medication, Graham has gradually improved and is now able to live independently.

“His Cotard’s has ebbed away and his capacity to take pleasure in life has returned,” Zeman confirmed.

Still, Graham acknowledged: “I couldn’t say I’m really back to normal, but I feel a lot better now and go out and do things around the house.

“I don’t feel that brain-dead any more. Things just feel a bit bizarre sometimes.”

“I’m not afraid of death,” he added. “But that’s not to do with what happened.

“We’re all going to die sometime. I’m just lucky to be alive now.”

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

How to join the indy100's free WhatsApp channel

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings

Top 100

The Conversation (0)