News

Narjas Zatat

May 21, 2018

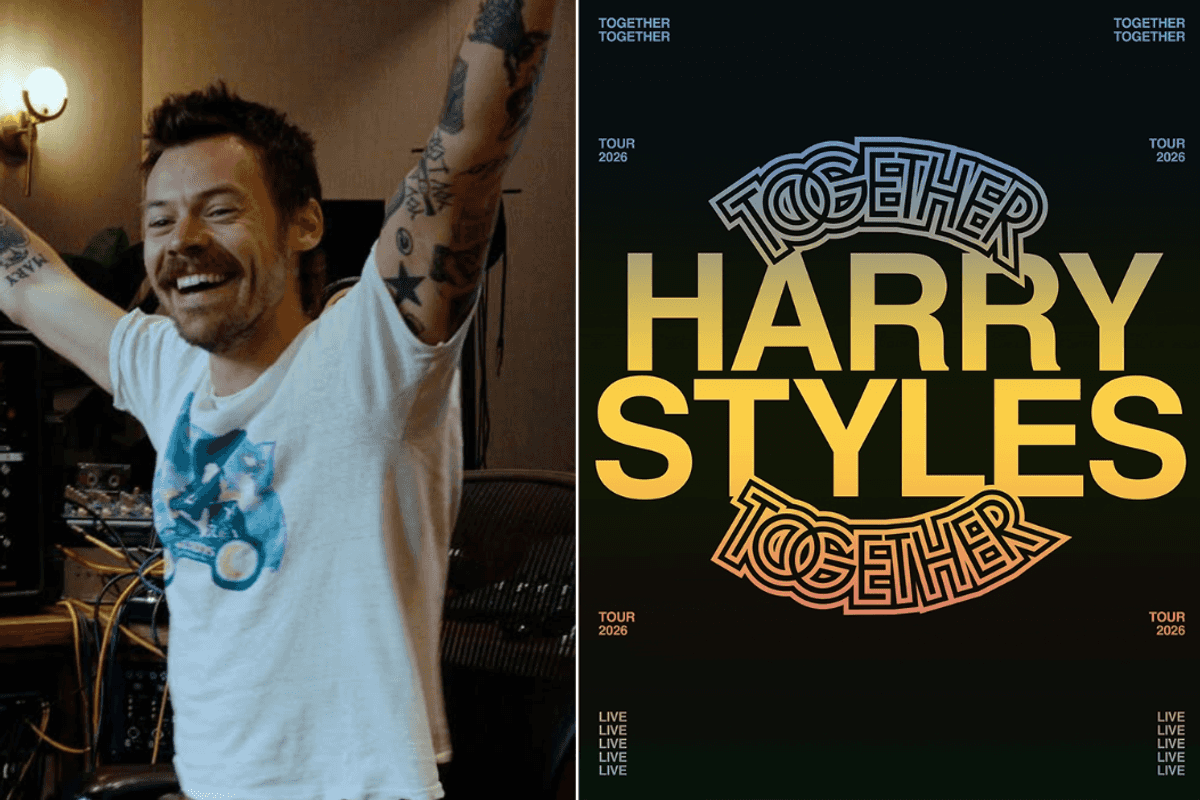

Picture:

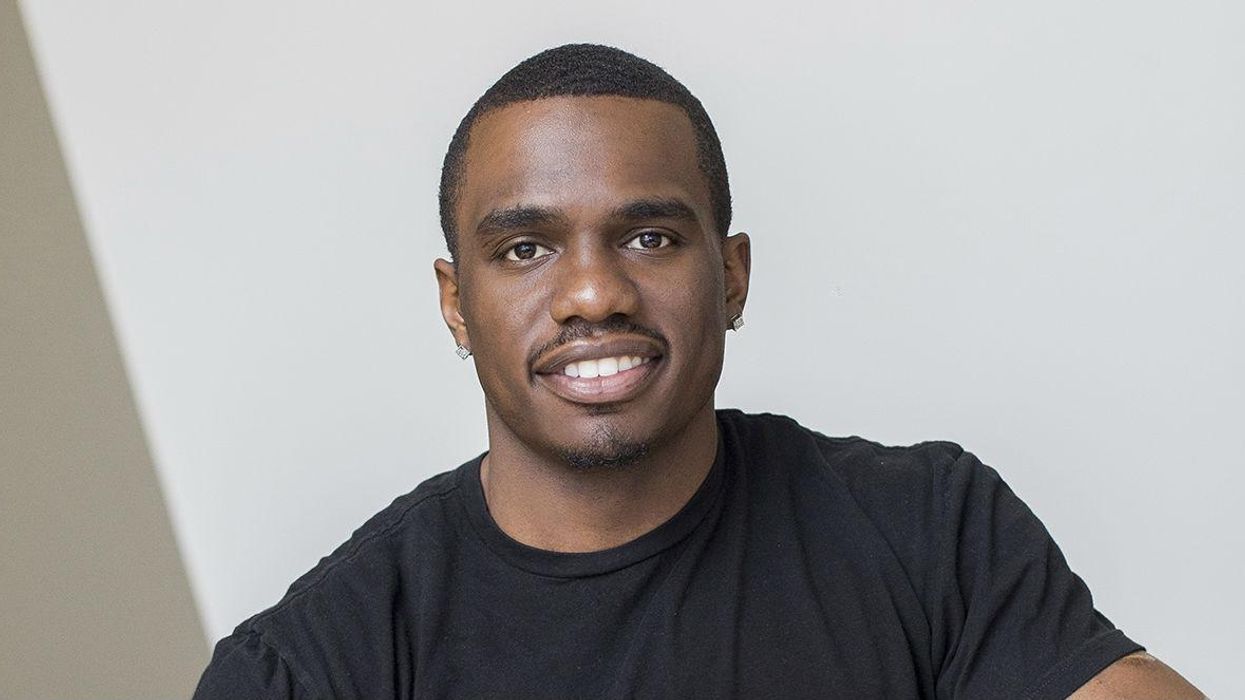

Rwenshaun Miller

In 2006, Rwenshaun Miller was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, leading him to be hospitalised, and to withdraw from university.

Miller embarked on a long road to recovery and learned to understand his triggers - and now dedicates his life into breaking down stigma attached to mental health disorders.

Eventually, he returned to university and became a therapist, a public speaker, a writer and a staunch mental health advocate. Miller started a not-for-profit organisation called Eustress, and his initiatives, ‘Let’s Talk About It’, ’Why You Stressing’ and his weekly national conference call ‘Locker Room Talk’ is raising awareness about mental health among the black and minority community in the US. He strives to create a safe space where people, particularly black men, can talk about their mental health.

His dedication to the community didn't go unnoticed, and he received a national APAF Award for Advancing Minority Mental Health.

Now he is pursuing a PhD in International Psychology - and spoke to indy100 about male mental health, toxic masculinity and the important work he does for his community in Charlotte, North Carolina.

You were diagnosed with bipolar disorder. What was it like, hearing that?

It was something that scared me, something that I didn’t want to acknowledge and something that I wanted to ignore.

Because of where I came from (athlete, top scholar) I felt like that couldn’t be me. I couldn’t be the one who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. I didn’t know what it meant.

The initial stages was that I hid it. The only people who knew about my diagnosis was my doctor and my close family members and I actually hid it for seven years.

My initial stage of recovery - going through treatment, medication and therapy, I actually stopped it. I felt like I was cured and I wanted to go back to school and when I went back to school, I didn’t want anyone seeing a pill bottle or see me going to therapy so I just felt like I didn’t need it anymore.

"I was diagnosed with Bipolar I [a feature of which is hearing voices]. I started hearing voices as well. I started self-medicating with alcohol. I would drink a fifth of tequila every other day. I did that for three and a half, four years.

"During that time, I attempted suicide twice".

That, for Miller, was the final straw: he needed to get help.

“It’s not a death sentence,” he said, “It’s something you have to acknowledge and learn how to adapt [to]”. Miller learned that understanding his triggers helped him to prevent the likelihood of spiralling into depression.

"And then to manage those things, I had to make sure I stick to a strict regiment. To work out. Watching what I eat – what we put into our bodies can greatly affect how we think".

One of the things you talk about is black mental health. Can you tell me about this? What kind of challenges does the black and minority community face when it comes to discussing mental health?

With black mental health, one of the key things is stigma. Stigma arises from ignorance around what mental health is and isn’t.

Also, what do particular disorders actually mean? And then also [knowing] that it can affect anybody.

A lot of times when dealing with things, especially in the black community, we rely heavily on the church.

"Some people feel like they can pray it away but that’s not the only thing you should be doing to get better - definitely not knocking any type of religious beliefs - but sometimes understanding that you need a little bit more help from a trained professional to address these issues.

"In the black community it’s about education, and it’s about breaking down those walls.

"It comes down to being in touch with your feelings and emotions and understanding and placing terms with certain feelings that we feel probably all our lives. That could be whether you get anxious when a police officer gets behind you, or you get anxious when you’re ready to take a test and your chest tightens up and you start to sweat.

"Just putting a term with that so you can identify it when it happens and understand why it happens. You can address it in different ways."

When I was growing up I was told ‘black people don’t go to therapy’. That’s something for rich white people. So there’s also a class thing as well – many people can’t afford therapy. Or it’s not a top priority because we’re facing so many other issues. You’re trying to worry about keeping the lights on. You’re trying to worry about how you’re going to eat. You’re not worrying about therapy. That’s something way down the line.

If you’re living check to check then you’re not actually worried about investing in your mental health because you’re still trying to survive.

How can mental health professionals help bridge the gap?

One thing that really helped me out was going to a black male therapist during my periods of depression and different phases during my disorder.

It’s about making sure that representation matters and showing that representation.

When it comes down to addressing mental health issues, we have to incorporate cultural factors. Those cultural factors are not able to be addressed by someone who is not of that culture.

"I host a weekly radio show call called ‘Locker Room Talk’ for men of colour and we just get on the call and talk about different issues that affect our mental health whether it be relationships politics, jobs, families – anything.

"It’s a nationwide call and people can just chime in – you don’t even have to speak if you don’t want to. We create that sense of community.

"It’s been going on a year and a half. We do it every Wednesday night".

Toxic masculinity is an aspect of society that makes it difficult for men to talk about mental health issues, and as a result mental health is often a taboo topic for men. How do you break down these barriers?

"I create spaces for African American men to talk amongst each other. I understand that I have to be vulnerable with them so they can see that it’s okay to be vulnerable with me.

"Also understanding I can’t be too pushy. You can’t force someone to talk about their feelings. We’ve been conditioned all our life to not talk about emotion. We’ve been conditioned to just suck it up. ‘Men don’t cry’ and ‘All you need to do as a man is provide for your family’. You have to create spaces and not judge anyone".

As black men we wear so many masks. Whether that be – I always tell me friends, when I get up in the morning and leave the house, I have to think about who I am interacting with, what clothes do I need to wear so I’m not judged for my character but also how to speak. How I shake someone’s hand.

At what point are you able to be yourself 100 per cent?

Being black, especially in America, the majority doesn’t understand that we’re constantly running through our minds, what particular mask we need to [wear] to make sure that we meet that social norm or even dispel the myths that certain people may have about us.

Do men respond better to other men talking about mental health?

Yes definitely!

"I appreciate all of the movements that help raise awareness about mental health. But I also want to push individuals not only to be aware but also to create action.

"Eustress does mental health first aid training, in the community, churches, schools, to actually focus on these preventative measures to reduce the likelihood of suicide and hospitalisations".

If you have been affected by this article, you can contact the following organisations for support:

More: Man deftly explains how toxic masculinity can lead to gun violence

More: Powerful video explains toxic masculinity and why all men should be feminists

Top 100

The Conversation (0)