Harriet Brewis

Mar 18, 2024

Rare orca pod filmed swimming close to California shores

Channel Islands National Park

Scientists in Canada have discovered what they believe to be a whole new type of orca, and these ones like hunting other whales.

The researchers, based at the University of British Columbia (UBC), identified the group as a new population, after watching them hunt the likes of sperm whales in the open ocean off the west coast of the US.

The pack of 49 killer whales couldn’t be matched with any known animals through photos or descriptions, leading the UBC team to carefully consider their status.

"It's pretty unique to find a new population,” UBC professor Dr Andrew Trites, who co-authored a study on the find, said in a statement.

“It takes a long time to gather photos and observations to recognise that there's something different about these killer whales.”

Based on their analysis, Prof Trites and his colleagues posit that the group could belong to a subpopulation of transient killer whales or a unique oceanic population found in waters off the coast of California and Oregon.

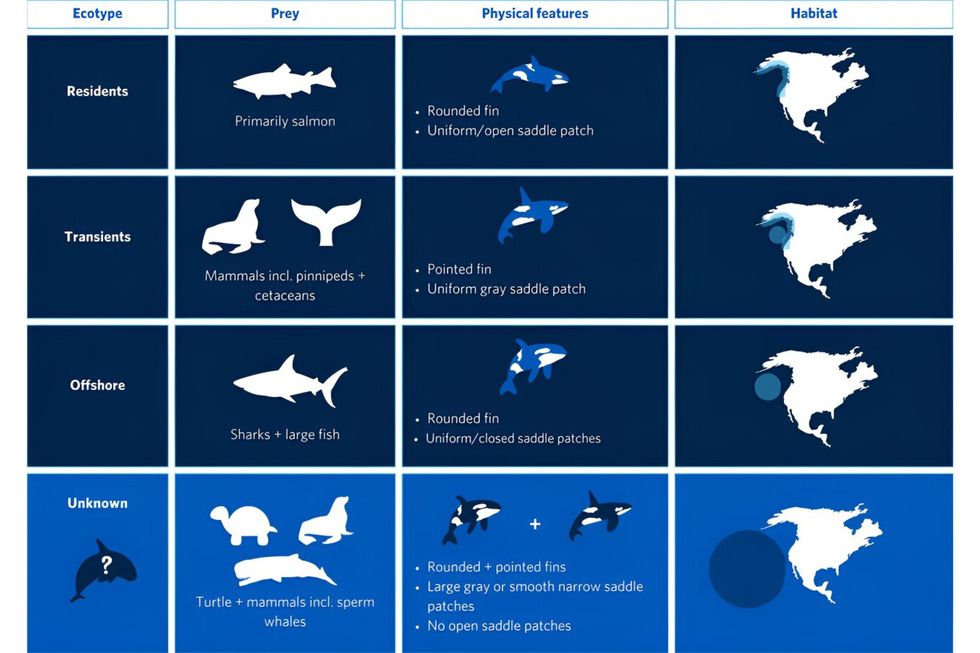

Three ecotypes of orca are already known to live along this stretch of the coastline. They are referred to as “residents,” “transients,” and “offshores”.

Transients, also known as Bigg’s killer whales, are a genetically and culturally distinct population of orcas within the Pacific Northwest which prey exclusively on marine mammals, the Orca Conservancy notes on its website.

The name “transient” was coined by killer whale researcher Dr. Michael Bigg who observed their behaviour as transient or more nomadic.

The mysterious pack of 49 had previously been spotted, but the UBC’s new paper features observations and evidence gathered from nine encounters with them – recorded between 1997 to 2021 – which is enough to form a solid hypothesis, the researchers said.

"The open ocean is the largest habitat on our planet, and observations of killer whales in the high seas are rare," co-author Josh McInnes, a master's student at UBC, explained.

"In this case, we're beginning to get a sense of killer whale movements in the open ocean and how their ecology and behaviour differs from populations inhabiting coastal areas."

Recalling one of the first encounters researchers had with a pod of these killer whales, McInnes noted that they took on a herd of nine adult female sperm whales, “eventually making off with one”.

“It is the first time killer whales have been reported to attack sperm whales on the West Coast," he said.

"Other encounters include an attack on a pygmy sperm whale, predation on a northern elephant seal and Risso's dolphin, and what appeared to be a post-meal lull after scavenging a leatherback turtle."

There were also physical clues that this group represents something unique.

Almost all of the orcas were scarred with bite marks from cookiecutter sharks – a small, cigar-shaped species of shark which lives in the open oceans.

These marks led the team to deduce that the new population must principally inhabit deep waters far from land.

The orcas also show bodily differences from the three main ecotypes, most notably on and around their fins.

"While the sizes and shapes of the dorsal fins and saddle patches (grey or white patches by the fin) are similar to transient and offshore ecotypes, the shape of their fins varied, from pointed-like transients to rounded-like offshore killer whales," McInnes explained.

"Their saddle patch patterns also differed, with some having large uniformly grey saddle patches and others having smooth narrow saddle patches similar to those seen in killer whales in tropical regions."

The researchers hope to document more sightings of the mysterious pack and learn more about them, for example, by gathering data on the orcas' calls and genetic information from DNA samples.

This will help them further investigate how these killer whales may differ, or not, from already documented populations.

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings

Top 100

The Conversation (0)