Showbiz

Paul Anthony Jones

Apr 01, 2016

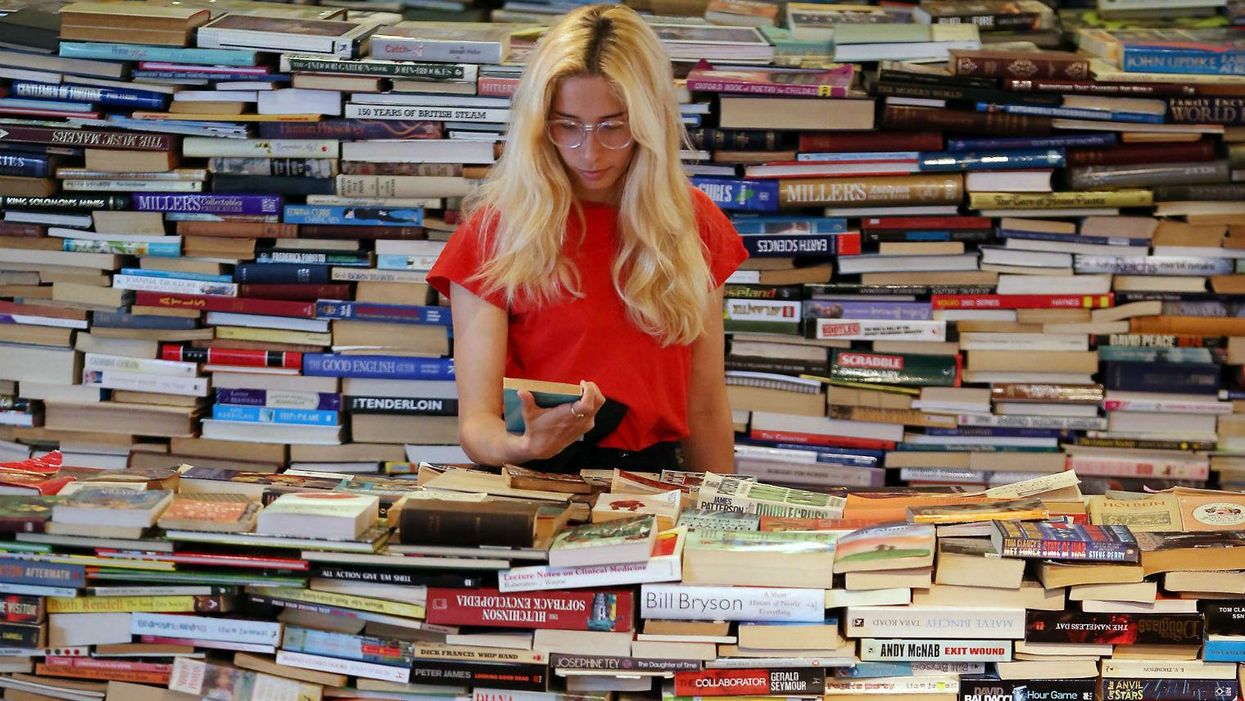

Picture: Getty

The English language is full of confusing words and overlapping meanings, which can make ensuring (or should that be insuring?) that you’ve picked the right word for the right context a minefield.

The differences between some of these pairs of confusables just need to be remembered, like canvas and canvass. Others have clever tricks and features that can help tell them apart – like the fact that, although something can be unfortunate, it can’t be unfortuitous (because a fortuitous event can be either good or bad).

And others, like the 10 listed here, become easier the more you know about them, as delving into their histories can help to remove any confusion...

1. BATED and BAITED

According to Oxford Dictionaries, around 1 in every 3 records of the phrase “bated breath” in the Oxford Corpus is spelled incorrectly, as “baited.”

Baited with an I is the same bait that you use when going fishing.

Bated without an I is totally unrelated, and comes from an ancient English word, bate, meaning “to beat down,” “restrain” or “suppress” – it’s the same word we use when we say that a storm has abated – which makes “bated breath” literally “held breath.”

2. BERTH and BIRTH

If a ship’s cabin sleeps two people, then it’s two-berth not two-birth (which would imply instead that it was about to deliver twins).

You want berth with an E here because, although no one is quite sure where the word comes from, this berth is probably descended from the verb bear, in the sense that the cabin is able to bear (i.e. hold) two people.

3. COUNCIL and COUNSEL

Council and counsel can both be used as nouns (in the sense of “an assembly of people” and “good advice or direction”) but only counsel with an SE can be used as a verb (“to give advice or direction”).

Both are derived ultimately from Latin, but while council comes from the Latin word calare, meaning “to call or proclaim officially” (which makes it an etymological cousin of calendar), counsel with an S comes from the same root as consult. So while a council is “called” together, you might “consult” someone for their good counsel.

4. ILLICIT and ELICIT

The initial letters of illicit (meaning “forbidden by law”) and elicit (meaning “to draw out”) give us the clue here. The I of illicit is actually the prefix in–, which is being used here to form a negative word as it is in inexpensive and indefensible.

The E of elicit is the prefix ex–, which is here used to form a word bearing some sense of “out” or “from”, like exhale and exterior. The –licit in both words is also entirely unrelated: in illicit it comes from the Latin verb licere, meaning “to allow” (as in licence), whereas in elicit it derives from the Latin lacere, meaning “to lure” (which is also where the word delicious comes from).

5. AFFECT and EFFECT

Another tricky pair of words that can be told apart by their prefixes is affect (which is usually a verb) and effect (which is usually a noun).

The root of both is the Latin facere, meaning “to make”, but while the E of effect comes from the same prefix as elicit, ex–, the A of affect comes from the prefix ad–, which is used to form words bearing some sense of “towards”, “on” or “a coming together” like adjoin or ashore. To affect ultimately means to have an effect on something, while an effect is an outcome.

6. GRISLY and GRIZZLY

If something is horrible to look at then it’s grisly, not grizzly. Grizzly with two Zs is a descendent of the French word for “grey”, gris, and comes from the older use of grizzled to mean “grey-haired” (despite grizzly being another name for a brown bear, of course).

Grisly with an S is a descendent of grise, a Middle English word meaning “to shudder with fear”.

7. HOARD and HORDE

Around a quarter of all the citations of the word hoard (a noun meaning a store of valuables, or a verb meaning “to accumulate” or “stockpile”) in the Oxford English Corpus are incorrect, and should really be horde (a large group of people).

In English, hoard is the older of the two and derives from an Old English word for treasure – wordhoard was an Old English word for a person’s vocabulary. Horde is completely unrelated, and has an E on the end of it because it comes from an old Turkish word, ordu, for an encampment.

8. TORTUOUS and TORTUROUS

Confusion often arises between these two not only because of their similar spellings, but because something that’s tortuous can often seem torturous.

Tortuous without the extra R means “full of twists and turns”, and is derived from a Latin word, tortus, for a twist, or a twisting, winding route (which makes it a relative of torque). If something is torturous then it’s akin to torture, hence the extra R.

9. OBTUSE and ABSTRUSE

If something is obtuse, then it’s blunt or insensitive. If something is abstruse then it’s difficult to understand. These two are often muddled up because of the similarity of obtuse to obscure, which is itself closer in meaning to abstruse; etymologically, all three are unrelated.

Obtuse literally means “beaten against” (and is a cousin of contusion, another word for a bruise) and so means “blunted”. Abstruse literally means “pushed away” (and is related to words like is related to words like intrusion and protrusion), and so has connotations of concealment and hiddenness. Obscure, for what it’s worth, literally means “darkened” or “put in the shade.”

10. BALMY and BARMY

Is the weather balmy or barmy? It’s balmy with an L if you’re talking about something pleasantly warm—literally, something as pleasant as balm, in the sense of an aromatic, healing lotion or salve.

It’s barmy with an R when you’re talking about something (or someone) foolish or crazy—literally, someone as frothy and as flighty as barm, which is the froth that forms the head of a pint of beer.

Paul Anthony Jones is an author who runs the @HaggardHawks Twitter account. You can check out his website here

Top 100

The Conversation (0)