Science & Tech

Harriet Brewis

May 02, 2025

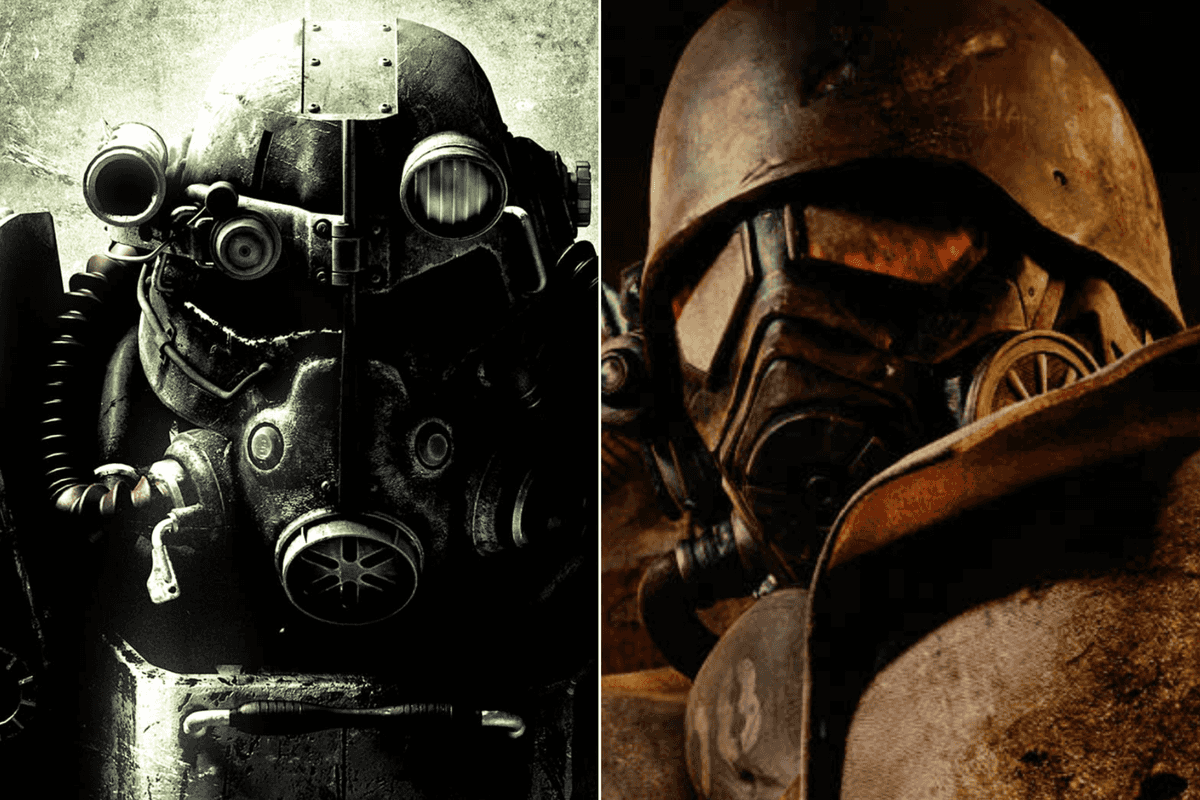

CITIES OF THE WORLD - Petra

Switch - Discover More / VideoElephant

For almost 2,000 years, a once-bustling city in the desert of Saudi Arabia was left abandoned to the sands of time.

Hegra, a thriving international trade hub in the first century AD, fell into a steady decline after it was annexed by the Roman empire in 106 AD.

Then, in the centuries that followed, it was all but forgotten: occasionally mentioned by pilgrims on their way to Mecca, but left largely untouched.

Yet languishing in the burning sun for nearly two millennia left the extraordinary site remarkably well-preserved.

And now it has finally opened up to both tourists and experts who are hailing it as the “key to unlocking the secrets of an almost-forgotten civilisation”.

What was Hegra?

Hegra, also known as Mada'in Salih or Al-Hijr, was the second city of the Nabatean civilisation – an enigmatic peoples who once dominated the trade routes through Arabia and Jordan; from Egypt to the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia.

The settlement lies at the foot of the Hijaz Mountains, 1,100 kilometres (around 684 miles) from the Saudi capital Riyadh – once a meeting point for a number of different civilisations.

The site consists of some 111 remarkably intricate tombs and 130 wells, cut into sandstone outcrops, which bear a striking resemblance to those found in the ancient site of Petra in Jordan.

This is unsurprising given that Petra, situated some 500 kilometres (around 310 miles) north of Hegra was the capital of the Nabatean Kingdom.

Who were the Nabataens?

The Nabataeans were desert-dwelling nomads turned expert merchants who controlled much of the incense and spice trade routes throughout the region.

By commandeering the supply of aromatics, including frankincense and myrrh, as well as the likes of sugar, cotton and peppercorn, they became wealthy and influential, as The Smithsonian Magazine notes.

The Nabateans prospered from the 4th century BC until the 1st century AD, when the Roman Empire claimed their territory, which included modern-day Jordan, Egypt’s Sinai peninsula, and parts of Saudi Arabia, Israel and Syria.

Gradually, the Nabataean identity was lost – or at least forgotten by the West entirely – until Petra was “rediscovered” by Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812.

The issue with understanding the Nabateans is that they left behind such scant first-hand history.

Indeed, most of what we know about them comes from the ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians. For example, Diodorus of Sicily wrote of them: “While there are many Arabian tribes who use the desert as pasture, the Nabataeans far surpass the others in wealth, although they are not much more than 10,000 in number.”

“The reason we don’t know much about them is because we don’t have books or sources written by them that tell us about the way they lived and died and worshipped their gods,” Laila Nehmé, an archeologist involved in excavations of the site, told the Smithsonian.

“We have some sources that are external, so people who talk about them. They did not leave any large mythological texts like the ones we have for Gilgamesh and Mesopotamia. We don’t have their mythology.”

And yet, evidence suggests that the Nabateans were pioneers in architecture and hydraulics – using their skills to harness the challenges of a harsh desert environment.

They even built natural water pipes around their beautifully carved structures to protect them from natural erosion – a move which significantly contributed to the site’s preservation.

“These people were creative, innovative, imaginative, pioneering,” David Graf, a Nabatean specialist at the University of Miami, also told the Smithsonian, adding that their ingenuity “blew [his] mind.”

Meanwhile, Wayne Bowen, professor of history at the University of Central Florida, told CNN: “We’ve all heard of the Assyrians, we’ve all heard of the Mesopotamians. But [the Nabateans] stood up to the Romans, they stood up to the Hellenistic Greeks, they had this incredible system of cisterns in the desert, controlled the trade routes.

“I think they just get absorbed in the story of the growth of the Roman Empire.”

What has Hegra taught us about this mysterious civilisation?

Whilst Hegra is home to just over 100 tombs, which is far fewer than the 600 plus found at Petra, many of these are in far better condition. This has enabled experts to notice the influence of classical Greek and Roman architecture on the buildings’ design.

Among the carvings are depictions of sphinxes, eagles and griffins, which were important symbols for a number of other ancient civilisations, including the Egyptians and Persians, as well as the Greeks and Romans.

Nehmé described the style as “Arab Baroque”, explaining: “Because it is a mixture of influences: we have some Mesopotamian, Iranian, Greek, Egyptian.”

“You can borrow something completely from a civilization and try to reproduce it, which is not what they did,” she continued. “They borrowed from various places and built their own original models.”

Furthermore, excavations by scientists, which only properly began in 2008, have also shed light on burial techniques employed by the Nabateans.

Vegetable oil and resin from trees and shrubs were used to preserve bodies. These were then wrapped in layers of fabric and leather before a garland of dates was placed around the neck, as the Telegraph notes.

In addition, more than 30 of the monumental tombs feature clear inscriptions offering up details about their owners, including their names and sometimes their role in the community.

Inside, glass beads, bronze bracelets, seed necklaces, embroidered handkerchiefs, coins and other artefacts have been found which offer further insight into life and customs at the time.

Some of the monuments bear women’s names, indicating their legal right to possess such tombs, as well as texts specifying which of their descendents could inherit them, National Geographic reports.

In addition, some of the inscriptions include ominous curses directed at anyone tempted to violate the site.

What does the future look like for Hegra?

In 2008, Hegra became Saudi Arabia’s first UNESCO World Heritage site, cementing its status as an area of extraordinary value.

And yet, it wasn’t until September 2019 that the country launched tourist visas, enabling visitors to experience the site for themselves.

Now, experts say it is time for the world to open their eyes to the value of this archaeological treasure trove and to recognise the Nabateans among the ancient greats.

“For a tourist going to Hegra, you need to know more than seeing the tombs and the inscriptions and then coming away without knowing who produced them and when,” Graf told The Smithsonian.

“It should evoke in any good tourist with any kind of intellectual curiosity: who produced these tombs? Who are the people who created Hegra? Where did they come from? How long were they here? To have the context of Hegra is very important.”

This article was originally published on 13 August 2024

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

How to join the indy100's free WhatsApp channel

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings

Top 100

The Conversation (0)