News

Jake Hall

May 07, 2018

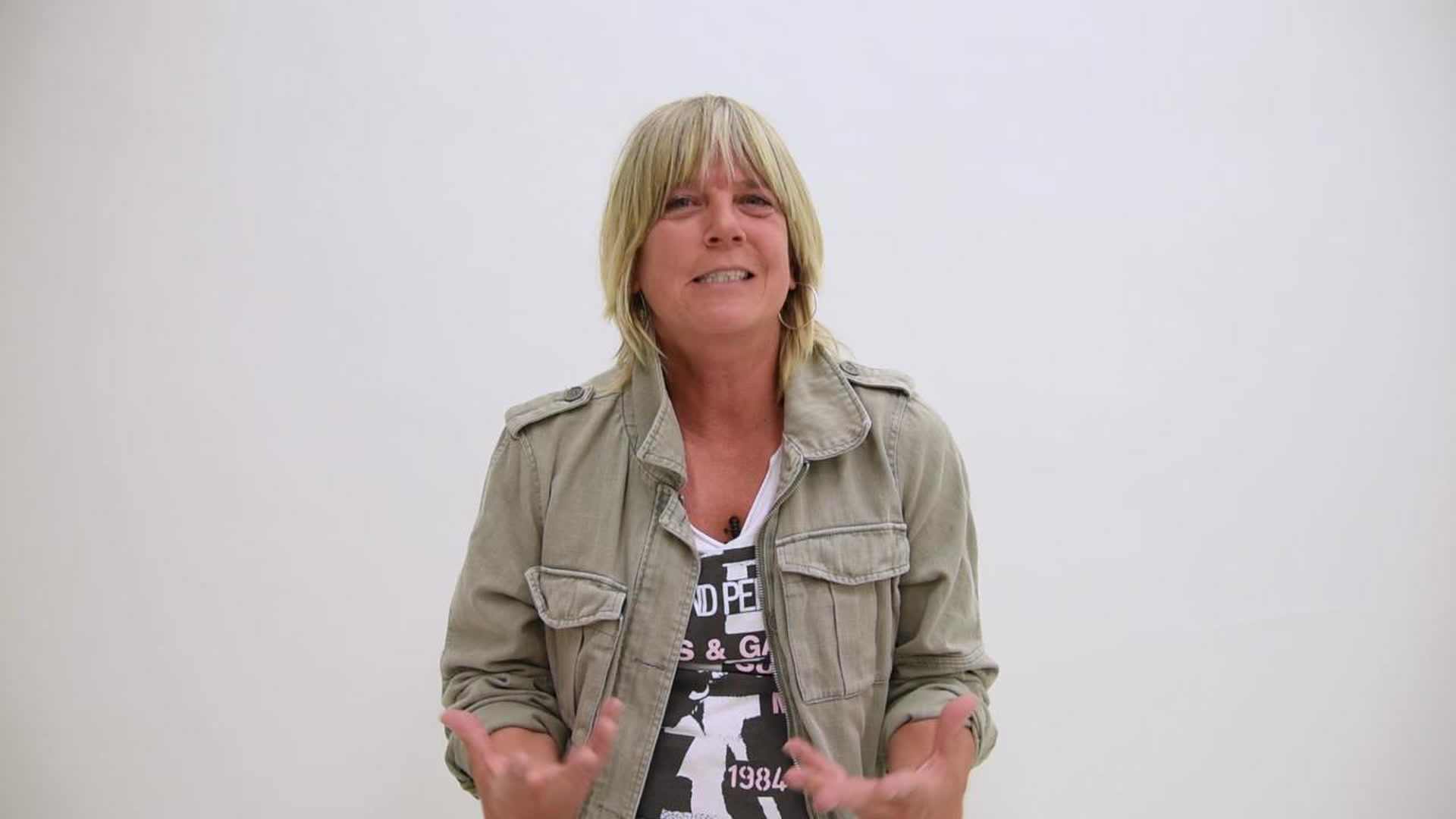

“I write very personally,” smiles trans author Juno Roche as we begin to discuss her recently-released book, Queer Sex. “I use my vagina as my entry point, because it’s the most personal thing.”

Roche isn’t exaggerating. It only takes a quick glimpse at her opening chapter, which explores the differences between her fantasies and her realities at length, to prove this point. In the context of a society that often avoids discussions about sex – particularly anything which deviates from vanilla, heterosexual sex – or treats them as taboo, Queer Sex feels genuinely revelatory.

“I had already written some articles and started to explore trans sexuality, but they were quite short, and it’s really difficult to ever get an editor to agree to a series,” she explains of the book’s conception. “But I just felt like it was the right time to write a book.”

I had seen a few things, but we were a few years past the media ‘tipping point’ and it felt like none of this coverage had any impact on ordinary trans lives.

The ‘tipping point’ Roche is referring to came around the same time that TIME Magazine boldly splashed the headline 'The Transgender Tipping Point over an image of actor Laverne Cox. The message was clear: trans people were now more visible than ever, and this visibility had to be a good thing. Right?

“I was getting really angry with the normativity of it all,” recalls Roche. “There was so much emphasis on ‘normal’ – all trans celebrities just looked like they weren’t trans, and that went for both men and women. They could just blend into any room. But even just to get to that point, they had to go through so many different processes.”

I realised that the one thing we hadn’t been allowed to do was just be enough as we were.

Although Roche repeatedly praises high-profile activists and lauds them for sparking important conversations, she also describes frustration at the lack of diversity within trans representation.

These observations aren’t necessarily new, but they certainly aren’t mainstream. Author Janet Mock coined the term ‘pretty privilege’ to describe the ways in which being conventionally attractive has afforded her certain advantages, whereas model Hari Nef gave an incisive, impassioned TED talk about ‘passing privilege’ – itself a problematic term – and how adherance to beauty standards can literally save lives.

Arguably, this is because the media celebrates femininity and is easily lured by the clickbait potential of the ‘before and after’ stories we so often see.

People seem to think that ‘transition’ is just a series of steps on the way to getting a cock or a vagina – they think that that’s always the ultimate goal.

“How can I describe it?” Roche hesitates for a second before laughing: “It’s like a home makeover show – this used to be a 1930s terrace, and now it looks a spaceship!”

But in reality – and I’ve been saying this for years – if you can’t accept a trans man with a vagina, or a trans woman with a penis, then you don’t accept trans-ness.

“If the country you live in doesn’t have gender reassignment surgery available through free healthcare, then the majority of people in that country are not going to be able to afford it.”

This is rarely depicted by media outlets more concerned with debating the validity of trans identities than offering nuanced explorations of the problems unique to the trans community. Roche is also connected to the Sophia Forum, a charity which advocates for women living with HIV. Statistics show that these women are disproportionately likely to live below the poverty line and face intimate partner violence.

But Roche, as politically conscious and articulate as she is, tries to sidestep facts and statistics. Instead, she has chosen to embark upon a project which saw her travel the country to conduct no-holds-barred interviews with trans, queer and non-binary people about their sex lives – but not before diving into the intimate details of her own.

“I’ve been HIV+ for more than twenty years now, which is difficult for anybody. But for women, and trans women in particular, it’s really tough.”

So, to put myself out there and say that I want intimacy, that I want somebody to fuck me or let me fuck them – it felt radical, and vulnerable.

“Once I put those two words together and ended up with ‘radical vulnerability’, it felt like something we had been denied as a community, so occupying that space felt empowering.”

Incidentally, Roche begins the book by describing the ways in which she felt undesirable; she describes a mismatch between her fantasies and her sexual reality whilst also opening up about the ways that gender realignment surgery reconfigured her desires.

It’s worth pointing out here that all trans identities are valid, and that surgical transition isn’t necessarily the choice for anyone. Furthermore, gross speculation about trans people can often lead to intrusive questions about genitalia.

This decision to write about her own vagina took time, but Roche now reels off hilarious anecdotes about her own experiences and the ways in which surgery tied in to sexuality.

When you’ve had surgery, you’re full of packing.

They then take it all out. It’s a bit like a magic trick – you’re just laid there thinking, ‘I can’t believe it’s still coming out!’ What else is in there, a giraffe?!

“Then, they get a speculum, shove it in you and tell you what depth you’ve got. At that point, I thought a few things, the first was that there was no feeling, no nerve endings – it’s essentially like cock and ball skin turned inside out and put back inside. I’m not denigrating it by the way – I think it’s magical.”

I wrote a piece recently where I compared my vagina to Judy Chicago’s ‘Dinner Party’, because I see it as a feminist work of art.

“Anyway, when I asked he said the feeling would come around my clitoris, and then he told me my depth. I was just thinking, ‘why is that a thing?’ I had been fucked for years, by a lot of men and a lot of women, but I remember just thinking, ‘why is he telling me? I don’t want to be fucked.’ At least I didn’t think I did.”

“It took me about a year to come to the conclusion that this wasn’t a vagina in the conventional sense – it was my queer space. I have friends that call it their ‘transgina’, but now I talk about my genitalia being upcycled, almost given a second lease of life!”

This willingness to discuss usually taboo subjects permeates every interview in the book. Because Roche is so intimate, so blessed with that rare ability to make anyone feel at ease in her company, she is able to ask the questions most would be intimidated to ask. The result is a book that reads almost like a transcript of conversations between close friends, one which veers between salacious stories and moments of genuine poignance. Drugs, dysphoria, addiction: no stones are left unturned.

“The thing is, these people completely trusted me. Everyone in this book knows my writing, and they know that it comes off the back of some twenty years and fighting and campaigning, from the days of ACT UP to queer spaces now.”

I was on stage ten years ago delivering a keynote at a conference where no trans person had spoken before. I was booed off stage.

People know that I’ve taken all the chances, and that I’ve done my time.

This genuine rapport crackles throughout the pages. In fact, it’s almost like Roche explores her sexuality vicariously through the experiences of her subjects, learning more about her own desires along the way.

“I actually think I had to examine my own desires. Historically, we have anointed ourselves as successful if we manage to get a cisgender partner. That felt a little bit like internalised transphobia to me. It felt like, if I couldn’t go to bed with a masculine person that happened to have a vagina, then I was kind of hating a little piece of myself.”

“So I did some looking around and questioning of what I found attractive, and I couldn’t figure out what that was.”

When I wrote on Tinder that I was looking for a ‘masculine’ partner, the responses I received just made me think: ‘Fuck off!’

“Men would offer to ‘treat me like a lady’, whereas women would ask if I liked going to football. No! So I went on this exploration of what it meant to be attracted to the construct of ‘masculinity’, and what that meant from a queer point of view. I started finding trans, and queer people more generally, really exciting and challenging because it was like we were letting go and giving ourselves room to breathe. That’s where the really sexy stuff happens.”

This progressive mindset is, unfortunately, not exactly represented in mainstream media.

In fact, trans voices are often included only when they can issue a response – a statement of self-defence – to mainstream commentators attempting to denigrate their existence.

“I was consistently being asked to respond to people that were being really horrible about us, and you know what it’s like – some would pay £250, others £275, and at the end of the day we all have bills. But then, about two years ago, I just thought ‘I can’t do this any more,’ so I stopped and my income plummeted.”

Conversations around trans identities are often hugely philosophical to the extent that they’re dehumanising.

They also detract from real progress: reform of the 2004 Gender Recognition Act has been halted by transphobes and media backlash, whereas just last week the Labour Party saw around 300 members quit when it announced trans women could be included in all-women shortlists.

Last week in the US, a trans woman had her request to leave a disciplinary unit – in a men’s prison – rejected by a judge. She was brutally raped just hours later.

All these conversations around trans identity are just: ‘I’m a real woman.’ ‘No you’re not.’ ‘Yes I am.’ ‘No you’re not.’

So I thought: ‘What about if I say ‘no, I’m not a real women.’ What would it be like to just say: I’m transgender, that’s my identity and that’s it.’ I’m interested in thinking about how we shape a community around being trans.

Roche speaks with an irresistible confidence which permeates her work and sets it apart from her contemporaries. Queer Sex resists the usual narrative and, refreshingly, doesn’t aim to offer answers or tart itself up as an ‘expert guide’ – “I fucking hate that term,” she cackles. This lack of pretence, coupled with frequent bursts of laughter and a few filthy jokes, has resonated with even mainstream media outlets, essentially making her one of just a few prominent trans commentators in the UK

“It feels good to create a different kind of trans-ness in the media. Actually, Cosmopolitan recently did a big piece on the book, and the journalist was quite nervous and said she didn’t want to get it wrong. But the thing is, I could tell within just five minutes of talking to her that she was genuine. That was really funny actually.”

Someone that was featured in the book got in touch and just said: ‘Fuck, I can’t believe I’m talking about wanking in Cosmopolitan!

“But that’s good, because we need more coverage which moves away from the depressing narrative that all trans people are going to try and kill themselves.”

“No matter how true that might be, I feel like if there is a young trans kid struggling with suicidal thoughts then showing them something fun and sexy is much more likely to stop them from trying to kill themselves than a piece which says all people like them try to kill themselves.”

This desire to genuinely help extends past her work in the media; she also dedicates some of her spare time to mentoring and gives one specific example of a trans teacher being misgendered constantly at work. As someone with experience in the field, Roche has been strategically placed to give advice, offer coping mechanisms and sit in on school meetings in order to discuss the ways in which trans staff members should be treated.

I worked in a school years ago, and I remember someone calling out across the classroom and saying, ‘Are you going to have the op?’

This was while I was just trying to enjoy my Manor House fruit cake and a cup of tea!

“Obviously I just thought, ‘What op?’”

This is a common misconception – surgical transition has often been referred to in shorthand as one operation, when in reality it’s a lengthy set of surgeries which differs from person to person.

“I thought, in a way, I don’t mind being asked that question as long as people are prepared for me to turn around and say: ‘No, I’ve got a dick and I want to use it.’ And that would be a perfectly fine response – there are still an awful lot of problems with trans surgeries, especially for trans men, so it makes a lot of sense for people to keep their original genitals if they feel like they can, and if it’s not too dysphoric. Because then they’ll have big old cums – proper, gut-busting orgasms. I think that’s really important. Orgasms are really important.”

In a way, I don’t mind having those really honest conversations – as long as the other side is prepared to have them on our terms, not on theirs.

But that’s the problem – there’s still an enormous lack of trans voices in mainstream media, and even the few commentators who do gain success are often subjected to hideous online transphobia or asked to debate rampant transphobes. In fact, a slew of high-profile trans, queer and non-binary activists have recently taken to Twitter to state their joint refusal of a Channel 4 debate show which, they say, has raised a number of red flags.

In reality, these are missed opportunities for nuanced conversation and the kind of hilarious, refreshing insight that permeates Queer Sex.

By making herself visible and platforming a series of other vital voices, Roche has offered an antidote to the soulless, often pointless conversations around trans issues we usually see in the media. Better still, she’s offered a genuinely useful tool to young queer kids starved of inclusive sex education.

“I just want these kids to feel able to have a giggle and touch, explore their own body now – whether they’re a trans woman who has had surgery, or whether they’re nineteen and they’re thinking about it, I want them to try and visualise what they want between their legs and then make themselves cum.”

“I want them to have fun! That might mean having a sneaky read if they’ve ordered it on Amazon and their parents don’t know.”

Yes, transphobia does still exist, but ultimately I want these kids to breathe easily, take the time to laugh and recognise that they can still have a fabulous life.

More: Author Juno Roche debunks six common myths about trans people

Top 100

The Conversation (0)