Harriet Brewis

Oct 04, 2024

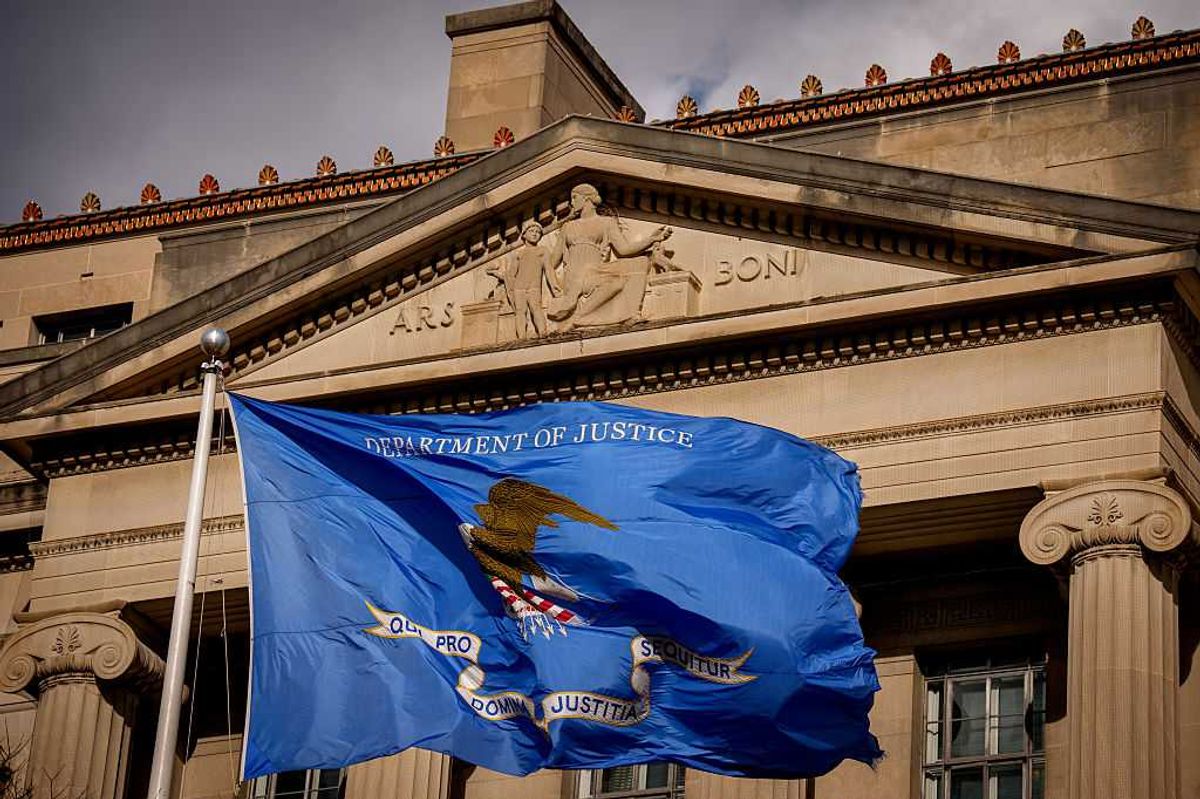

La Rinconada sits some 17,000 feet above sea level

(iStock)

Many of us suffer from altitude sickness if we so much as look at a mountain. And yet, tens of millions of people across the world live thousands of feet above sea level.

Most of the world's highest-placed settlements can be found in South America, Central Asia and East Africa, with Wenquan in China sitting at a stomach-dropping 15,980 feet (4,870 metres) high.

However, even this pales in comparison to the remotest and loftiest of them all: a town tucked into the Peruvian Andes known as “Devil’s Paradise”.

Officially called La Rinconada, its 60,000-odd inhabitants live between 16,404 feet (5,000 metres) and 17,388 feet (5,300 metres) above sea level, making it the highest permanent settlement on the planet, as Live Science notes.

And, as you might expect, life here is no picnic.

Residents must make do without running water, garbage disposal and even a functioning sewage system, and they’re forced to rely on food imported from lower altitude regions.

Plus, it took until the 2000s for electricity to finally be installed in the town.

So why, you might well ask, would people choose to live there in the first place?

The answer is... money. Or, more specifically, gold. La Rinconada started out as a temporary mining settlement more than 60 years ago and remains a controversial part of the industry.

The nickname “Devil’s Paradise” apparently derives from the town’s lawlessness and governance by “competing mafia mobs”.

In a piece for the Dissident Voice newsletter, author Peter Koenig describes the “crime gang-run city” as “one of the most horrific places on earth.”

“La Rinconada looks and smells like a wide-open garbage dump, infested by a slowly meandering yellowish-brownish mercury-contaminated brew – tailings from illegal gold mining – what used to be a pristine mountain lake,” Koenig writes.

“The thin, oxygen-poor air is loaded with mercury vapour that slowly penetrates people’s lungs, affecting over time the nervous system, memory, body motor, often leading to paralysis and early death. [The] average life expectancy of a mine worker is 30-35 years, about half of Peruvian’s average life expectancy.”

According to Koening, “human rights do not exist in Rinconada” and people can be killed for “carrying a rock that may contain some tiny veins of gold.”

Furthermore, child labour and prostitution are “commonplace”, he claims, as are sex and drug trafficking.

And yet, he says, miners come to the town “voluntarily”.

“Nobody forces them,” he writes. “Most are poor and jobless. They come for necessity.”

He goes on: “The dream of getting rich in the goldmine makes them accept the most horrendous working and living conditions: surviving in an open dump-ground of everything, garbage, toxic heavy metals, wading in mercury-polluted tailings, thin air, contaminated by poisonous vapours, no heating, most of the year sub-freezing temperatures –trash and debris everywhere.”

Koenig notes that some stay “temporarily” – between six months and two years. While others stay “until they die”.

Certainly, La Rinconada is not for the faint-hearted, and just stepping foot in the town poses significant problems.

Anyone who wasn’t born at high altitude and ventures to such heights will notice their breathing and heart rates quickly rising. This is because less oxygen is available in the air, meaning the lungs and heart need to work harder.

"By the time you're at about 4,500 metres [14,763 ft], the same breath of air that you take here [at sea level] has about 60 per cent of the oxygen molecules, so that's a big stress," Cynthia Beall, an anthropologist at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, told Live Science.

Some people also develop a condition called acute mountain sickness (AMS), whose symptoms include headaches, fatigue, nausea and a loss of appetite.

Still, after about a week or two at high altitude, a person's heart and breathing rates typically begin to drop as the body begins to make more red blood cells and haemoglobin to compensate for the low oxygen levels, Beall explained.

And those who settle down in places like La Rinconada show an amazing capacity to adapt to these tough conditions.

"There's pretty good evidence from around the world that there are either slight or very large increases in lung volume for people who are exposed to high altitude, particularly before adolescence," Beall said.

Andean highlanders, for example, tend to have a high concentration of haemoglobin in their blood which makes their blood thicker.

And whilst this allows them to carry more oxygen in their blood, it also means that they are at risk of developing a condition called chronic mountain sickness (CMS), which occurs when the body produces an excess of red blood cells.

CMS afflicts people who live at altitudes higher than 10,000 feet (3,050 metres) for months or years and causes symptoms including fatigue, shortness of breath and aches and pains.

Around a quarter of La Rinconada’s inhabitants are estimated to suffer from CMS.

The best treatment for CMS is simply to descend to a lower altitude, Tatum Simonson, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, told Live Science.

However, the alternative is to perform regular bloodletting and take a drug called acetazolamide, which reduces red blood cell production.

Nevertheless, the long-term safety and effectiveness of these treatments remain unknown.

In other words, as we said before, La Rinconada is not for the faint-hearted.

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

How to join the indy100's free WhatsApp channel

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings

Top 100

The Conversation (0)