After three months of lockdown there's a lot of things people have been talking about missing. Their loved ones, a coffee they haven't made themselves, pub gardens, birthday parties, hairdressers...

But this week we've all discovered that actually the one thing the British public was secretly angling for was... fast fashion. Call me naive but I, for one, was not expecting this.

Even at the best of times, walking around a crammed clothes shop, arms aching from the weight of 15 different florals-for-spring polyester dresses, only to eventually realise none of them work and panic-buying half a dozen £4 graphic tees to try and make the whole expedition worth it can't possibly strike many of us as the dream.

Add to that the fact that for most of us there's literally no reason to ever get out of our pyjamas at the moment and the hoards of people queueing for hours to get into Primark as it reopened this week seem even more baffling.

Aside from the obvious jokes about the shocking images of these crowds, the clear demand for fast fashion betrays another truth about our society that may be hard to reconcile: the endless cycle of tragedy of 2020 appears to have taught us nothing when it comes to what indulgences we prioritise.

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, we've seen an unprecedented outpouring of support for the least privileged in society.

People of all political persuasions (even the most abhorrent) rallied behind care workers, who were (and are still) risking their lives, often for minimum wage, in order to protect the most vulnerable. We denounced the NHS surcharge which saw migrant workers forced to pay to use the healthcare system they are often propping up. Questions were posed about the very nature of capitalism. There was a collective outrage about the people the furlough scheme left behind. And the disproportionate death rate for BAME people became a national talking point that politicians are still grappling with now.

Meanwhile the one positive lockdown impact that many were quick to rave about was the so-called "nature is healing" phenomenon. With our lifestyles drastically changed, there was no end to stories about the positive environmental impact this has had (although there's evidence that the pandemic may also have contributed to landfill waste).

The past three weeks have also seen a global resurgence in activism around racial inequality. The death of George Floyd sparked global Black Lives Matter protests, and people calling out instances of racism have gained more traction than ever before, with editors losing their jobs and TV shows being pulled from the air.

It's almost as if it were human nature which has, to some small degree, healed.

And then... shops reopened, and it seems everything went out the window.

It's important to mention that it wasn't just Primark which had huge queues going round the block. High end stores saw a similar wave of customers, although they caused less outrage. Part of the reason for this is that we live in a classist society, always poised to mock and shame less privileged people for their choices, while the middle class faces no such prejudice.

Lots has been written about this dichotomy, but it's important to note that it's not just less affluent people who shop in Primark. Since its launch, it's been positioned as the go-to option for anyone who wants to indulge in fashion trends without paying the high price tag. I would also hazard a guess that customers typically skew female more than they do working class.

But this isn't really about Primark – it's about all the high street shops and all the people who couldn't wait to get back in there and spend their hard-earned money on clothes.

There's no sense in shaming individual people for enjoying fashion. I absolutely understand the emotional value of a banging outfit you feel incredible in.

But it's impossible not to be struck by the sheer collective glee at being able to buy cheap clothes, and the level of cognitive dissonance it requires for anyone socially aware.

For starters, fast fashion presents huge environmental issues.

Often cited statistics suggest that the fashion industry is the second most polluting industry after oil. While doubts have been cast on the methodology behind this assertion, there is no question that the manufacturing of clothes has a huge environmental impact.

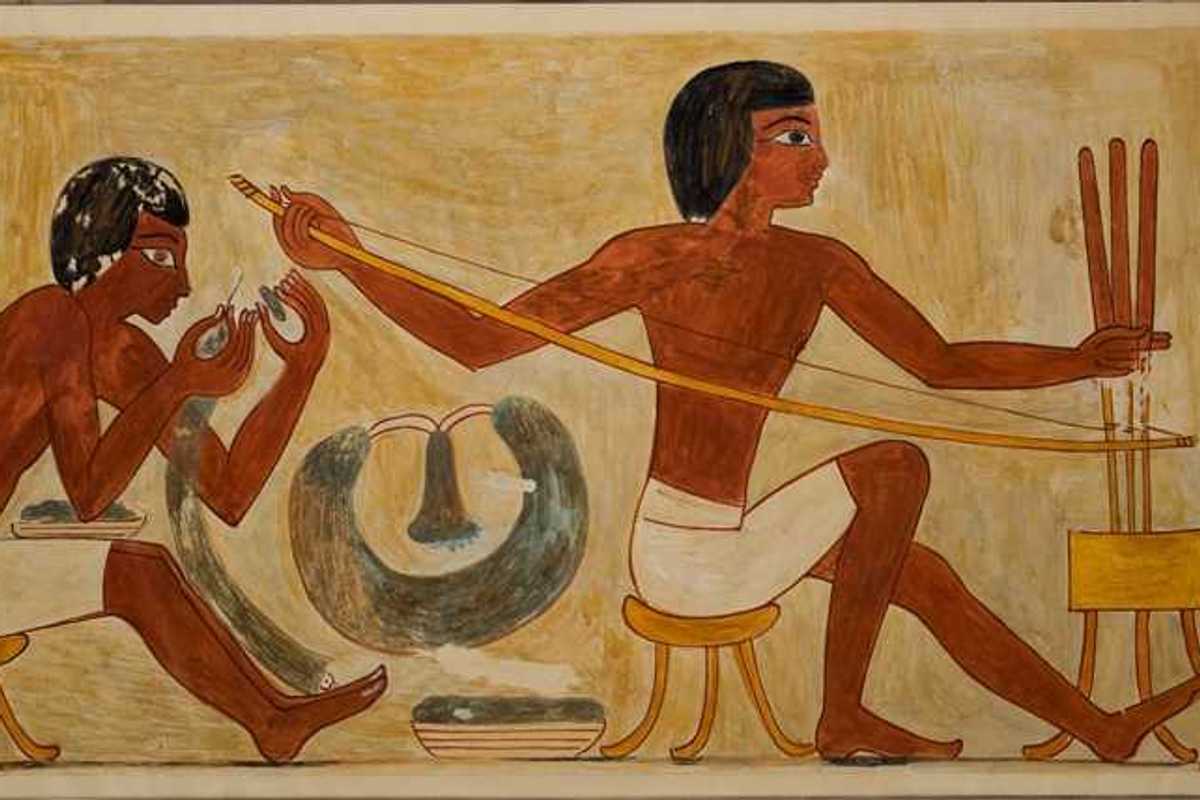

The making of the clothes themselves is a huge problem.

According to the UN, a typical pair of jeans requires 2,000 gallons of water to manufacture, while T-shirts average at about 3,000. This is because cotton – which most of our clothes are probably made of – is an incredibly water-intensive crop.

And it's not just water, according sustainable fashion platform to Fashion For Good, conventional cotton production accounts for one sixth of all pesticides used globally, wreaking havoc with local communities. The World Health Organisation estimates that in developing countries approximately 20,000 individuals die of cancer and suffer miscarriages as a result of chemicals sprayed on conventional cotton.

If you think that's bad, synthetic fabrics like nylon and polyester are arguably even worse as they require crude oil to manufacture, and fossil fuel extraction is one of the most environmentally damaging industries out there.

There's little alternative – leather is responsible for huge amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. Wool is probably your best bet, but it's not exactly a fabric you can build an entire wardrobe from.

All this without considering the huge environmental impact of clothes once they're discarded, which is more readily than any of us may want to admit.

In 2014, we bought 60 per cent more clothes than in 2000, while only keeping them for half as long. Truly, the amount of clothes we throw out is shocking. Figures show that every second, the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles is landfilled or burned.

in London alone we throw away 11 million items of clothing every week. Twenty-three per cent of Londoners' clothes are never worn. It would take the entire population of London 15 years to drink the water footprint of London’s unworn clothes.

"But wait!" I hear you cry. "I don't throw my clothes in the bin, I take them to charity shops!" Cute. But not a solution. For a variety of reasons, clothes banks and charity shops generally only keep between 10 and 30 per cent of the items donated to them. The rest end up being sent to developing countries at huge environmental cost, and usually end up in landfill anyway.

Basically, there's pretty much no such thing as an item of clothing you can buy without environmental damage attached to it.

And there's a human cost too.

For a society suddenly so intent on tweeting about workers' rights and racial inequality, we sure are happy to ignore that little label on most garments saying "made in Bangladesh". Textile workers are typically women of colour who are paid "derisory wages and forced to work long hours in appalling conditions", according to the UN.

Even most of the so-called ethical brands can't usually guarantee decent working conditions for their entire supply and manufacturing chain.

Of course, this is the case for a number of industries. Capitalism is not constructed to protect the planet or the rights of the humans who inhabit it – especially the less privileged ones.

But it's hard to think of another industry which we so willingly buy into, so regularly, and for no real need. Yes, we all have to wear clothes, but do they have to be trendy? Do they have to be brand new? Do they have to be replaced every season? Do we really need seven pairs of jeans rather than two? No.

None of this is news. The social impact of fashion has been a talking point for years. So much so that we've seen an explosion in the market trying to capitalise on a more "sustainable" approach to clothing – from writing books about minimalist capsule wardrobes to funding entire brands which sell "ethically manufactured" and "environmentally sourced" items.

And yet... still there are queues snaking round the block to get into high street stores.

We shouldn't blame the individuals in that line, or those in line for the high-end equivalents.

Ultimately, we live in a society which has indoctrinated us into believing that key to happiness lies in the purchasing of more stuff.

And clothes – particularly women's clothes – are marketed as a catch-all solution to all our problems. Shopping is "self-care"! we're told. A great outfit will make us nail that job interview! Slay that Tinder date! Become the best version of ourselves!

Of course, none of this is true.

A great outfit will line the pockets of the capitalist machine, make us poorer, take up valuable space in our brains and our homes, and feed into immediate gratification which inevitably leads to the crash, which you then have to buy more to pick yourself up from.

For a minute there, it almost seemed like the horrifying events of 2020 might have rewired us into realising this, and we may begin to prioritise protecting the planet and standing in solidarity with the workers we've overlooked for generations.

Sadly, it seems that – on the high street, and in the manufacturing factories no one wants to think about – it's business as usual.